Route 66

Route 66 is commonly known as few different names, from Will Rogers Highway, The Main Street of America to the Mother Road, each identifies the famous stretch of highway that extends from Chicago, Illinois through Santa Monica, California. Along the way, the route weaves its way through Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.

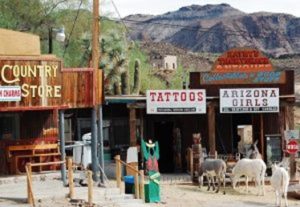

Photo credit: Adam Naddsy

When people think of Route 66, it often brings up memories and images of mom-and-pop shops that are a representative of uncomplicated times. Even today, many of the stores, motels, gas stations, cafes, parks, trading posts, bridges and roads are still standing along Route 66, available for people to experience the past and reminisce about old times.

People doing business along the route were thriving due to the growing popularity of the highway, and those same people later fought to keep the highway alive in the face of the growing threat of being sidestepped by the new Interstate Highway System.

The Gold Rush, The Model T & The Need For A Paved Road

Before Route 66 was even a thought, America was expanding and began to grow westward. People were curious and wanted to know what was beyond the land that was right in front of them. There were vast unexplored lands beyond the Mississippi River and the American people’s imaginations ran wild with ideas of possibilities. There were no established trails yet, except the ones the mountain men blazed themselves as they followed the beaver along the traces left by the Native Americans.

The introduction of the automobile changed the face of America forever. The arrival of Ford’s Model T in 1908 had a dramatic effect on the American populace, as automobiles became accessible to the common person. The automobile provided a new economic base that was the first of its kind. Now Americans started to travel. They were no longer confined to the short distances that a horse could travel in a day. Journeys that would take many days on horseback or wagon now took a mere few hours.

History

There is a sense of freedom that Route 66 provided to its earliest travelers and for others a sense of nostalgia. The “Super-highway,” as it was thought of in 1926, represented extraordinary freedom to travel across the American West. Cyrus Avery from Tulsa, Oklahoma was a realtor and owner of a coal company who began acquiring oil leases. With the oil leases, it became essential to reach the desolate lands around him and the need for a roadway linking the Midwest to the western lands.

Bell Gas, the other way in Tulsa. Photo credit: Pete Zarria.

Connecting cities along the path soon became a reality. Together with John Woodruff, an entrepreneur from Springfield, Missouri, these two envisioned this magnificent idea of linking Chicago to Los Angeles and began lobbying efforts to promote the new highway and bring prosperity to Tulsa as well as other points west.

U.S. 66 was first signed into law in 1927 as one of the original U.S. Highways, however it was not completely paved for another eleven years in 1938. Despite their efforts in composing this new highway, the depression came and halted all efforts to finish Route 66. It wasn’t until 1933 when the depression lifted, that thousands of unemployed men began working on paving the road again. Road gangs paved the final stretches of the road as well. While other East/West highways existed at the time, most followed a linear course, excluding the rural communities that depended upon transportation for farm products and other goods.

Avery was unyielding that the route had a round number. He proposed number 60 to identify it, but Kentucky delegates who wanted a Virginia Beach, Virginia to Los Angeles highway to be called 60, already claimed this route number. Avery ended up settling on 66, which had not yet been assigned. Avery thought the double-digit number would be easy to remember and pleasant to say and hear.

The Dust Bowl

Traffic on the highway began to grow due to the geography it passed. Much of the highway was basically flat, which made it popular among truckers driving through the states. Additionally, the Dust Bowl in the 1930s brought about many farming families. They mainly came from Oklahoma, Arkansas, Kansas and Texas, heading west for agricultural jobs in California.

The Dust Bowl, also known as the Dirty Thirties, was a period of brutal dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the US and Canadian prairies during the 1930s; severe drought and a failure to apply dryland farming methods to prevent wind erosion, caused the phenomenon. The drought came in three waves, 1934, 1936, and 1939–40, but some regions of the High Plains experienced drought conditions for as many as eight years.

During the drought of the 1930s, the unanchored soil turned to dust, which the prevailing winds blew away in huge clouds that sometimes blackened the sky. These choking billows of dust, named “black blizzards” or “black rollers,” traveled cross-country, reaching as far as such East Coastt cities as New York City and Washington, D.C. On the Plains, they often reduced visibility to 1 meter (3.3 ft) or less.

The drought and erosion of the Dust Bowl affected 100,000,000 acres that centered on the panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma and touched adjacent sections of New Mexico, Colorado, and Kansas. The Dust Bowl forced tens of thousands of families to abandon their farms. Many of these families, who were often known derogatorily as “Okies” or “Arkies.” migrated to California.

Route 66 was the main road traveled during this time. During the depression, it also gave relief to communities located along the highway. The route passed through various small towns and, with the growing traffic on the highway, helped create the rise of mom-and-pop shops, such as service stations, restaurants and motor courts, which were all readily accessible to passing drivers.

Stories Of Route 66

Route 66 is filled with stories along each step of the road. However, one type of story that seems to prevail throughout Route 66 is the ghost story. There’s a fair share of haunted hotels, ghosts lurking in restaurants, and a few that simply seem to prefer to take a leisurely walk down old Route 66.

Haunted Luna Mansion In New Mexico

Although the Luna-Otero mansion is often know for its delicious steaks, hot chili, and great desserts, it is also known for its resident ghosts lurking about the Mansion. The marriages of Solomon Luna to Adelaida Otero, and Manuel A. Otero to Eloisa Luna in the late 1800’s united these two families into what became known as the Luna-Otero Dynasty. They occupied the mansion until the Santa Fe Railroad wanted a right-of-way through the Luna property in 1880, the projected railroad tracks were planned directly through the Luna estate. In order to gain their right-of-way, the railroad agreed to build a new home for Antonio Jose Luna and his family.

Luna-Otero Mansion Los Lunas, New Mexico. Photo credit: Graham Tiller.

When older generations died, the house was left in the hands of the remaining family members. In the early 1900s control passed to Soloman’s nephew, Eduardo Otero. In the 1920s numerous improvements to the mansion were made, including the addition of a solarium, a front portico, and ironwork that bordered the entire property. Eduardo’s wife, Josefita, also known as “Pepe,” was mainly responsible for these numerous efforts. Josefita fondly spent her days caring for her beautiful gardens and improving her fine home.

The mansion was eventually bought and renovated into a fine dining restaurant in the 1970s. At that time, the ghost of josefita began to appear. There are a couple of theories why. The first is that she didn’t like the renovations. Another theory is that maybe she wanted to hang around to make sure the new owners were doing a fine job on the home that she had spent so many years looking after. She was often seen dressed in 1920s period clothing and either walking up and down the stairs or sitting in a rocking chair slowly rocking back and forth as well as in two former bedrooms. It has been known that when one spirit appears another one often follows. There have been reports of other ghosts residing in the mansion as well.

Suicide Bridge In Pasadena

The grand 1913 Colorado Street Bridge in Pasadena, California not only amazed early travelers crossing this path, but also soon took on a more disturbing tone when people began to jump from the 150 foot bridge to their death. Within a decade of being built, locals had begun to call it the “Suicide Bridge.” This also brought about tales that the bridge was haunted by those ill-fated souls.

Suicide Bridge in Pasadena, CA. Photo credit: Cody R.

The beautiful concrete bridge extends 1,467 feet across the Arroyo Seco and is known for its Beaux Arts arches, ornate lamp posts and railings. When engineer John Drake Mercereau conceived the idea of curving the bridge, he created a work of art.

The first tragedy on the bridge occurred before construction was even completed. The first suicide occurred on November 16, 1919 and was followed by multiple others, especially during the Great Depression. It is estimated that more than 100 people took their lives leaping the 150 feet into the arroyo below over the years. One suicide, which was supposed to be a murder suicide, occurred on November 16, 1937. When a down on her luck, hopeless mother decided to throw her baby off of the bridge, she then leaped off as well. Miraculously, the baby was inadvertently thrown into nearby trees and survived.

According to the sagas, multiple spirits are said to roam the bridge itself as well as the arroyo below. Others have heard baffling cries coming from the canyon. One report tells of phantom man that is often seen wandering the bridge donning wire rimmed glasses. Other people have claimed to see a woman in a long flowing robe before vanishing as she throws herself off the side. The Colorado Street Bridge was part of Route 66 until 1940 when the Arroyo Seco Parkway opened.

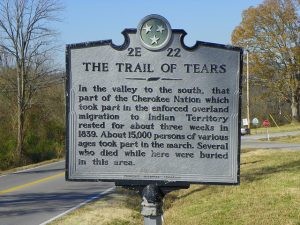

The Trail of Tears

After the Indian Removal Actof 1830, tens of thousands of Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw Indians were driven from their homelands in the southeast United States to reservations in Oklahoma. They suffered from exposure, disease and starvation. Thousands died, which gave the name to their path, the “Trail of Tears” One man who lived near Jerome, Missouri, did not forget the Indians suffering. He spent years building them a tribute along Route 66.

Trail of Tears Historical Marker. Photo credit: J Stephen Conn.

One man, Larry Baggett, an eccentric elderly gentleman who lived just outside of Jerome along old Route 66, would often be woken up in the middle of the night from a knock on his door. However, when he would get up to answer, no one would be there. An old Cherokee Indian, who looked approximately 150 years old, visited Larry. The old Indian told Baggett that his house was built on the Trail of Tears and it was blocking the path.

The Indian explained how they were made to walk hundreds of miles and how the Cherokee had camped right near Larry’s home. Larry had already built a stone wall adjacent to his house before meeting the Cherokee man, but when they met, the Indian told him to put stairs there because the spirits were unable to get over the wall. Larry built those stairs to nowhere and when they were complete, the knocking stopped. Baggett originally acquired the property with the intention of building a campground, but these plans were changed when his wife died. Instead he built a tribute to the Trail of Tears. Locals and tourists remained intrigued about this monument along Route 66.

Route 66 & Pop Culture

Although Missouri was the birthplace of Route 66, Oklahoma is probably the most famed location on the entire route. There are many pop culture references that are set on Route 66 or events or stories that take place there. For instance, n 1928, Oklahoma native Andrew Hartley Payne brought dignity to the state by winning the “Bunion Derby,” which is a 3,400-mile race from Los Angeles to New York that extended through much of Route 66. Oklahoma possesses the longest section of the original Route 66, which equals about 400 miles.

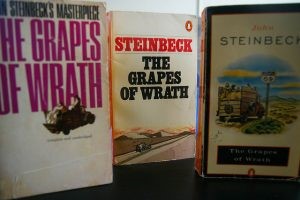

Additionally, several of the road’s most renowned travelers came from the state, including Woody Guthrie, Will Rogers and the fictional Joad family from John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, which gave the route its most recognized nickname. “66 is the mother road,” Steinbeck wrote, “the road of flight.”

There were also numerous songs dedicated to the famous Route 66. Bobby Troup’s song Route 66, which was recorded by Nat King Cole, the Rolling Stones, Depeche Mode and several others, advised, “Won’t you get hip to this timely tip/ When you make that California trip/ Get your kicks on Route 66.” There was also the television series on CBS from 1960 to 1964 entitled, Route 66. The show followed Tod Stiles (Martin Milner) and Buz Murdock (George Maharis) on their job-hunting travels across America in their Corvette convertible.

Jack Kerouac also wrote of Route 66. The main character, Sal Paradise, in his book On The Road, briefly traveled on Route 66 where it intersects Route 6 in Illinois, the road served as a symbol for members of the Beat Generation. Kerouac describes “the beatest characters in the country” swarming the sidewalks in Los Angeles. Among them, Kerouac notes, were the “longhaired brokendown hipsters straight off Route 66 from New York.

There are several other pop culture references as well. For instance, in the film, “Rainman,” much of it was shot along Route 66 in Oklahoma with Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman. Super 8 Hotel in El Reno, room 117 was preserved because the director, Barry Levinson filmed scenes of both Cruise and Hoffman there. Additionally, “Cadillac Ranch,” a song from Bruce Springsteen’s “The River” LP, was inspired by the roadside attraction near Amarillo, Texas. Famous actors, Clark Gable and Carole Lombard spent their honeymoon in the Oatman Hotel in Oatman, Ariz., on Route 66. It’s now a museum.

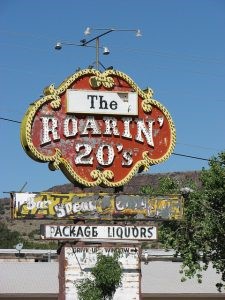

The Decline Of Route 66

Although the cultural and symbolic significance of Route 66 grew in the 1950s and 1960s, its physical presence began to fade. The “Family Vacation” started as a new American phenomenon in the 1950’s. Route 66 became a destination unto itself. With its caverns and caves, scenic mountains, beautiful canyons and sparkling deserts being heavily promoted by the U.S. 66 Highway Association, Route 66 became the ultimate road trip.

Cavern Inn Along Route 66; Peach Springs, AZ. Photo credit: El-Toro.

Oklahoma was the first state to deal the route its first official deathblow. In 1953, the Turner Turnpike (I-44) between Tulsa and Oklahoma City opened, bypassing 100 miles of the legendary Mother Road. Other states followed in Oklahoma’s footsteps, while the federal government’s new four-lane, straight-as-an-arrow interstate system gobbled up section after section.

The Interstate Highway Act of 1956 allotted funds for 41,000 miles of freeway to accommodate the exponential increase in automobile traffic. Since Route 66 forged an efficient, direct path from the Midwest to the west coast, Interstate 40 directly paralleled it through most of the Southwest, rendering most stretches of the older highway obsolete. The residents and businesses along Route 66 felt the effects of I-40 immediately.

One woman, Mirna Delgadillo, daughter of Route 66 barber Angel Delgadillo, recounted what happened in Seligman, Arizona. She said, “Before the bypass, crossing the street was like taking your life into your hands, because there was so much traffic. And then after the bypass happened, we could lay in the street for hours and not worry about getting run over. Literally from one day to the next it went from being alive to being dead.” Small towns whose economies had flourished on Route 66 tourism lost the majority of their customers overnight; many businesses were forced to close or relocate nearer to an I-40 interchange.

Grants, New Mexico. Photo credit: Avi Dolgin.

On October 13, 1984, the outdated, poorly maintained remnants of U.S. Highway 66 fully surrendered to the interstate system when Interstate 40 at Williams, Arizona, circumvented the final section of the original road. The route was “replaced” by Interstates 55, 44, 40, 15 and 10. However, in response to the deep need to preserve the rich resources of the historic highway, Congress passed an act to create the Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program. The National Park Service administered the program, which collaborated with private property owners; non-profit organizations; and local, state, federal, and tribal governments to identify, prioritize, and address Route 66 preservation needs.