A Short History Of The Moors

Granada – the word in Spanish means pomegranate – a fruit brought to Spain by Moslem tribes from North Africa in the 8th century. They were known as the Moors and they came to Europe from what is now known as Morocco.

For nearly 800 years the Moors ruled in Granada and for nearly as long in a wider territory of that became known as Moorish Spain or Al Andalus. In Granada, where the Moors first came in 711, they built a fortress palace known as the Alhambra. It was never conquered by their enemies but in 1492 the Moors surrendered their citadel, by then the last outpost of Moorish Spain, to the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabel. It would bring to an end an era and mark the beginnings of the Spanish Inquisition.

But the Moors left behind a rich architectural and cultural legacy still apparent throughout the Iberian Peninsula and beyond today.

The Romans

Before the arrival of the Arabs, the Romans had built a small city on the western outskirts of its empire called Volubulis. Previously part of the North African Carthaginian Empire, it became part of the Roman Empire after Juba, the 2nd a local Berber king, married the daughter of Anthony and Cleopatra.

Thought to have been constructed in the 2nd and 3rd centuries during the reign of Emperor Caligula, it was buried by an earthquake in 1755 ,and wasn’t discovered again until just over 100 years ago, in 1915. Volubilis grew from a provincial outpost to a substantial capital on the outskirts of an empire, known as Roman Mauretania covering an area of about 100 hectares. It was important enough to have its own triumphal arch, the Gate of Tangier. It also contained small palaces and substantial houses with exquisite mosaic floors, still here today.

The Arabs Arrive

The Arabs invaded Morocco in 683, inspired to spread their new religion Islam. In 786 Arab leader, Idriss the 1st, who claimed direct descent from the Prophet Mohammad, arrived in V

olubilis and it marked the beginning of the end of the Roman city.

The local Berber tribes converted from Christianity and Idriss the 1st was buried in the hilltop town of Moulay Idriss, just three kilometres away. It’s still regarded as one of Morocco’s most holy sites. Then a small force of Arab and Berber warriors embarked series of raids across the Strait of Gibraltar into Southern Spain

The Omayads

So rapid was the Moors expansion into Spain that soon a capital was established in the city of Cordoba. The driving force behind the new Moskem settlement was Prince And Al Rahman who escaped here with his family after the fall of the Umayyad dynasty in Damascus in 725, and it’s replacement by the Baghdad based Abbasid dynasty,

He made the Meskita mosque the centrepiece of this new caliphate, which he began building on the site of a church 30 years after his arrival. It combined indigenous designs with those that borrowed features from the Great Mosque of Damascus.

The Idrisids

While And Al Rahman consolidated his power in Spain, in Morocco it was Idriss the 2nd, the son of Idriss the 1st, who who went on to establish the city of Fez, which remains to this day one of the great strongholds of the Islamic faith. Two thousand Arab families came to settle here in 814 followed by 8000 Arab families from Spain.

Fez is famous for its medieval Medina with its labyrinth of narrow streets and alleyways. This giant walled city, home to 70,000 people, is still the world’s largest urban car-free zone and everything today still needs to be brought in by hand pulled carts or even donkeys.

The heart of the city is the 9th century Kairaouine mosque, established in 859, which is also the sanctuary for tomb of Idriss the 2nd. The mosque contains what is thought to be the oldest university in the world. Over the centuries the mosque has been encased by the Medina surrounding it.

After the death of Idriss the 2nd a new dynasty came to power and they would found another great city and make it their capital. For nearly 500 years, and in particular during the 10th century, Cordoba was a beacon a civilisation – cultural capital that lived peacefully with a multi-ethnic population, including Jews and Christians.

The Almoravids

What is known today as the pink city, or Marrakech, was founded in 1062 by a Berber dynasty known as the Almoravids. Their most charismatic leader was Yousef Ben Tachfine.

The Almoravids constructed a 20-kilometre, eight-metre high mud wall around the city in 1126 , giving it thee distinct colour which survives to this day. Its has been repaired and rebuilt many times in the 900 years since.

The Almoravids introduced an ingenious underground irrigation system that still supports a vast palmerie outside Marrakech The Almoravid version of strict orthodox Islam spread across Morocco and into neighbouring Algeria.

And at the age of 80, Youssef Ben Tachfine launched a series of daring invasions of the Iberian peninsula.

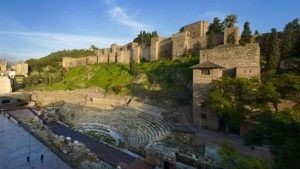

Moorish Forts

To protect their newly won territory the Moors built giant fortress palace complexes known as “Alcazabas”. Construction of some like old Alcazaba at Malaga had begun more than 200 years earlier, during the reign of Al Rahman’s Cordoba based dynasty, but the Almoravids embellished the Alcazaba adding many of the hundred towers that survive to this day.

The Alcazaba of Malaga

A series of fortified gates took visitors into the inner sanctum of the palace grounds. The Moors were renowned for their gardens, and the use of water delivered by simple but ingenious irrigation methods to create and ambiance of peace and tranquility to their surroundings.

The Moors also built more practical structures used for defense only. Further north west on the banks of the Guadiana River in Merida, where the Romans had built a massive bridge (the longest surviving from the ancient world), the Moors constructed an Alcazaba on the side of a previous Visigoth fortress.

And in Seville on the banks of the river Guadalquivir you find the “Torre del Oro” watchtower built in 1221. It is still there today.

The Moors territory stretched as far north as Zaragoza, near Barcelona, where they constructed a fortress palace which hundreds of years later would be occupied and converted by Spanish monarchs. Many conquests of the Iberian peninsula were launched from the modern day capital of Morocco, Rabat.

But right from the start the battles between Moors and Christians seesawed over the decades, a pattern which would be repeated over the centuries As early as the 11th century Moors would return from Spain on the occasion of military defeats and in Rabat they settled at the Rabat harbour entrance in an area known as the Kasbahs of the Ouidas. The unique blue and white washed homes of the refugees are still there today

Back in Fez, the Almoravids also embellished the city, in addition to their capital Marrakech. Skilled craftsmen were imported from Spain and countless new public buildings and fountains were erected. By 1145 there were 10,000 shops and 785 mosques.

But today very few monuments from a century of Almoravid rule remain. In Marrakech, the most significant is a small shrine known as the Koubba, now undergoing restorative work.

The Almorads

Roman Ruins of Volubilis

The Almoravids successors, the Almorads, were also Berbers but when they overthrow the Almoravids in 1147, they plundered and destroyed the Almoravid legacy, a trend that would be repeated over the centuries.

The most famous and expansive Almohad sultan was Yacoub el Mansour, who is remembered too for his victories over the Spanish and as a builder of great Mosques

Mansour’s most famous mosque was the Koutoubia in Marrakech. It’s 70-metre high tower became a prototype of the genre, it’s influence apparent in Moroccan minarets constructed since the 12th century. The design was also copied in the Moors’ Spanish territories.

The Marinids

After the death of Mansour, the Almorads were in turn overthrown by the Marinids, who achieved fresh victories in Spain and conquered Algeria. They made Fez their capital in 1248.

The Marinids were responsible for the Medersas, or Islamic boarding schools, that can be visited today. Medersa Bou Inania in Fez was built between 1351 and 1357 by Merinid Sultan Bou Inan. It’s been impressively restored with elaborate tile work and beautiful cedar lattice screens.

Bou Inan also built a medersa in Meknes completed a year later in 1358 . This is typical of the exquisite interior design common to Merimid monuments. Religious students 10 to 14 years of age slept in tiny rooms on the first floor.

Under the Merinids, many refugees arrived in Fez from Spain, as battles with Christian Spaniards intensified. The refugees settled on the other side of the river in a quarter known as Al Andalous. Among those arriving were skilled Granada craftsmen whose work can still be seen today.

Ceramics workshops still produce the intricate hand made tiles that decorate so much here and are now made for export. Copper work is also a proud artisan tradition, as is leatherwork. Tanneries within the Medina still process skins for leather goods.

Jews were among the refugees escaping to Fez following persecution in Spain. At one time a quarter of a million lived here in a specially created Mellah, or Jewish quarter. Their old houses remain, their open balconies looking into the street.

Less than a hundred Jews remain today, a bygone era symbolised now by the Jewish cemetery, where a sea of blindingly white tombs stretches down the hill from the Mellah.

The Merinid Sultans who welcomed the Jews were buried in far grander surroundings on a hilltop overlooking Fez. But the Merinid dynasty grew unpopular, protected by Syrian mercenaries and their tombs were ransacked and made ruinous long ago

The Merenids lost power because they started losing wars in Spain – and then ports in Morocco. Raising taxes to try to introduce new bronze cannons to keep up with European technology, they became hugely unpopular.

Merenid Tomb ruins, Fez

Seville’s massive cathedral, the world’s largest, is itself a former mosque. Its giant bell tower, the Giralda, used to be a minaret. The tower is 342-feet-high and remains one of the most important symbols of the city as it has been since medieval times. The Almorads used the Koutubia in Marrakech as a model for the Giralda. The tower’s first two-thirds is the former minaret built between 1184 and 1198. The upper third is Spanish Renaissance architecture. After Seville was taken by the Christians in 1248, the mosque was converted into a church. The final third of the building is an outstanding example of the Gothic and Baroque architectural styles.

In Rabat, Yacoub el Mansour’s great unfinished work, known as Hassan’s Tower, was to be the greatest mosque in western Islam. Mansour died before when it was half built and it remains in that state today.

Granada, The Alhambra And The Inquisition

Meanwhile in Southern Spain, or Al Andalus, today’s Andalucía, the Moors had continued building. It’s an architectural legacy that can still be seen today in the winding alleys of the old Jewish quarters, particularly in the Andalusian cities in the south such as Cordoba, Seville, and Granada. One of Moorish Spain’s most spectacular buildings, the Alhambra Palace, still stands.

Work had begun on the Alhambra fortifications in 889. But the complex evolved over several centuries with work on its three palaces not completed until the end of the 14th century.

In 1492, the Emirate of Grenada was the last bastion of Moorish Spain to fall to the La Reconquista led by the crusading Isabel and Ferdinand.

The last Moorish Emir, Boabdil, surrendered to the Spanish monarchs on the plains below the fortress. The Alhambra itself was never taken but the royal standard of the Catholic monarchs soon flew from the watchtower atop the fortress citadel. The Catholic monarchs then moved into what was the most exquisite of buildings that the Moors had created during their 800-year-rule.

The Alhambra complex is vast, covering 35 acres, and has a number of grand features. The protective Alcazaba, or fortress, at its western end is the oldest part of the complex and built on an isolated and precipitous headland making it impossible to take. The rest of the plateau comprised a number of earlier and later Moorish palaces enclosed by a fortified wall and 13 defence towers.

After the Reconquista, the Spanish monarch Charles the 5th built a giant Renaissance palace right in the heart of the complex. To this day it sits uneasily amongst the Moorish architecture of the Alhambra.

The main entrance to the Alhambra was the Gate of Judgement. Built in 1348 with its massive horseshoe-shaped arch, the Hand of Fatima, with fingers outstretched against the evil eye, is carved above the entrance.

The royal palace complex consists of three main palaces. The oldest is the most modest, and was used for business and administrative purposes. The Hall of the Ambassadors is the largest room and was used for welcoming important visitors.

Bou Inania Madrasa, Meknes

The entire complex overlooks the old district of Albayzin where Muslims continued to live for decades after the Reconquista.

Soon after the last Moors were overthrown, the Inquisition intensified and religious minorities tolerated under Islam were driven out too or killed – victims of a blood and barbarous witch hunt by inquisitors.

The Grand Inquisator, Tomas de Torquemada, ran 100,000 trials, burnt 2,000 at the stake and advised Ferdinand and Isabel to issue the edit of expulsion. This led to 100,000 Jews converting to Christianity and another 200,000 who didn’t being forced to leave the country.

The Alhambra, the most famous of Moorish palaces, may still be here today but after the Reconquista inquisitors tried to eradicate Muslim culture too, carrying out mass baptisms, burning Islamic books and banning the Arabic language. By 1500, about 300,000 Muslims had been baptised and converted under threat of expulsion. But these Moriscos, as they were known, were eventually expelled 100 years later.

The Christian victory over the Moors in Spain in 1492 had therefore resulted in mass exodus from the Iberian peninsula of both Moslems and Jews.

White Slaves

For more than 100 years embittered Moriscos, as they were known, were among those that took to the seas off the Iberian peninsula pirating European ships and enslaving their crews. The white slaves they captured were destined to slave prisons in North Africa like the one at Sale, next to Rabat, still here today. Its estimated that over a period of 100 years, 30,000 Europeans were captured and sold into Slavery. The Morisco raiding parties stretched as far east as Italy, where pirates attacked shipping along its western coast.

And it wasn’t just European slaves being seized by Moors. Moorish slaves were also taken by Europeans and sold in slave markets in port cities like Livorno. Here, a sculpture known as The Four Moors shows Ferdinand dei Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, towering over four shackled Moorish slaves. These giant bronze statues created by Tuscan sculptor Pietro Tacca, a pupil of Giambologna, were erected between 1623 and 1629. The statue of the Duke, the founder of Livorno who made a name for himself fighting the pirates, was erected 25 years earlier.

Although diminished of their Spanish territories the Moorish empire nevertheless remained a powerful economic force in North Africa in the 17th century. But it was trading goods rather than slaves that made Moorish cities such as Marrakech wealthy.

In the Medina of Marrakech one can still find many Caravanserais – nearly 150 still survive – where valuable merchandise was stored and where the merchants and traders who brought these cargoes from inland Africa could also stay in lodgings on the first floor.

The Saadians

The great beneficiaries of this lucrative trade, particularly in sugar, was Morocco’s new dynastic rulers: the Saadians.

Medina walls, Rabat

Overlooked by the Merinids, Marrakech in the late 16th century enjoyed a renaissance under the new Saadian dynasty. They established a Jewish Mella or quarter in 1558, where 6,000 Jews were relocated. Today, as with other mellahs in Moroccan cities, most Jews have left – just a small synagogue remains.

However, the Jews impact on cultural and commercial life in the city is felt to this day. The Al Badi Palace, a 360-room palace commissioned by famous Saadian sultan, Ahmad Al Mansour, was considered a wonder of its time. Featuring sunken gardens and reflective pools it was decorated in gold, turquoise and crystal, treasures all plundered by the later Allouite sultan, the infamous Moulay Ismail, who used them for his own palace in Meknes. Saadian sultan Al Mansour spared no expense in his glorious mausoleum. Also buried here were 60 members of his family and trusted Jewish advisors

Al Mansour died in spendour in 1603, but Moulay Ismail – who had plundered the palace – had the mausoleum walled up as well. It was only discovered by aerial photography nearly three hundred years later in 1917. Even today the tombs are only accessible through a small passageway in a nearby mosque.

Today, there are only traces in Marrakech of the refined tastes of Saadian artisans where original features have been painstakingly restored to their amazing colours, an indication of the vibrant decorations for which the Saadians were reknowned. Many of these Moorish architectural concepts come together in the traditional house or Riad, which form much of the accommodation in Medinas in Moroccan cities today.

The Allouites

When they assumed power from the Saadians, the Allouites – led by sultan Moulay Ismael – moved the capital from Fez to Meknes . The new sultan would become one of the most famous rulers in the history of Morocco.

Not lacking in ambition, Ismail built 12 grand palaces enclosed by 25 kilometres of walls and ramparts. Modelling himself on Louis XIV his summer palace was meant to be equivalent of Versailles.

Moulay Ismail made sumptuous gardens watered by great reservoirs and built the Gate Bab Mansour which still claims to be the grandest gate in all of Morocco. The inscription above its elaborately carved entrance reads:”I am the most beautiful gate in Morocco. I am like the moon in the sky. Property and wealth are written on my front.”

To support his vast army, Ismail built huge reservoirs which watered both the city and the massive stables, which could house 12000 cavalry horses. The animals were waited on hand and foot with a groom and a slave for each horse to ensure that all their needs were met. Today, the site is overrun with stray cats

Moroccan Palace Entrance

When he died many of Ismail’s grand projects were either incomplete or fell into ruins. But Moulay Ismail’s legacy remains undiminished. Four hundred years later the grand square where Moulay Ismail expected an army of 150000 slaves from Sudan, is a very different place – the thriving heart of modern city.

Modern Day

Today, Moulay Ismail´s magnificent walls are not used for war or defence. Instead, the walls enclose a beautiful golf course that was built by Ismail’s Allouite descendent, Hassan II.

Hassan II modernised the country adopting market-based economy where tourism was developed and encouraged.

His son, the current king, Mommmad VI, even built a surfing club in Rabat. But the royal family grip on power remains undiminished.

Hassan II died in 2003, and is buried in a magnificent tomb in Rabat, next to his father, Mohammad V, who was the last Sultan of Morocco before the title was changed to King in 1957.

The legacy of the Moors lives on both in Morocco and in the great buildings left behind in Spain and beyond. This remains of the worlds most enduring dynastic civilisations.