The Spanish Inquisition

One of the darker periods of Spanish history is the Spanish Inquisition, which entrenched Spain for over 350 years. Also known as The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, it was created in 1478 by Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile.

Following their kingdom-uniting marriage, the famous Catholic monarchs Fernando and Isabel had a huge project ahead of them. Not only did the two kingdoms of Aragón and Castilla become one amongst mixed opinions, but the monarchy was closing in on the remaining Moorish kingdoms with the end of the Reconquista. It was intended Catholic orthodoxy be maintained in their kingdoms whilst replacing the Medieval Inquisition, which was under Papal control.

To manage, unite and strengthen their enlarging and culturally diverse kingdom it was decided the means of unification would be through Catholic orthodoxy. Therefore in 1478, permission was requested from Pope Sixtux IV to establish a special sect of the Inquisition – permission he reluctantly granted, which began the Spanish Inquisition.

What followed was an era of severe censorship, paranoia, torture, autos-da-fé, death, and the persecution of heretics or anyone who deliberately disagreed with the principles of the Catholic church lasting lasted until 1834.

This period became the most substantive of the three different manifestations of the wider Christian Inquisition along with the Roman Inquisition and Portuguese Inquisition. This Inquisition operated in Spain and in all Spanish colonies and territories, which included the Canary Islands, the Spanish Netherlands, the Kingdom of Naples, and all Spanish possessions in North, Central, and South America. The Inquisition was originally intent was to ensure the orthodoxy of those who converted from Judaism and Islam. Regulating the faith of the newly converted intensified after royal decrees issued in 1492 and 1501 ordered Jews and Muslims to convert or leave Spain.

The monarchy feared the intervention of Jewish and Moorish alliances from oversees and forced non-Catholics to choose between conversion to or expulsion from the country to abolish any possibility of dissent. Those suspected of practicing Protestantism, non-Catholic-approved sexual acts, black magic or any other activity the monarchy deemed a threat, also were among the persecuted.

Within a few years later suspicions and paranoia arose again. This time regarding the loyalty of those conversos (converted Jews) and moriscos (converted Moors) to Catholicism. The Inquisition persued converts with suspicion, obsessed with the notion they had only convert to escape persecution, were continuing to practice their own religion covertly planning to undermine the church.

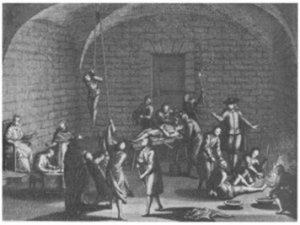

The inside of a jail of the Spanish Inquisition, priest supervising his scribe while men and women are suspended from pulleys, tortured on the rack or burnt with torches. Etching.This file comes from Wellcome Images, a website operated by Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation based in the United Kingdom

Religious Turmoil

Much of the Iberian Peninsula was dominated by Moors following their invasion of the peninsula in 711 until they were finally defeated in 1492. The re-conquest did not result in the expulsion of Muslims from Spain, instead producing a multi-religious society comprised of Catholics, Jews and Muslims. Larger cities such as Granada, Seville, Valladolid, the capital of Castile, and Barcelona, the capital of the Kingdom of Aragon, had large Jewish populations centered in juderias(Jewish Quarters).

The period was known as the Reconquista and produced a moderately peaceful co-existence with intermittent periods of conflict among Christians, Jews and Muslims in the peninsular kingdoms. There was a long tradition of Jewish service to the Aragon crown: Ferdinand’s father John II named Abiathar Crescas a Jew, as court astronomer and many other Jews occupied important posts both religious and political even Castile itself had an unofficial rabbi.

Nevertheless, towards the end of the fourteenth century in some parts of Spain there was a wave of anti-Semitism, encouraged by the preaching of Ferrant Martinez, archdeacon of Ecija. The pogroms of June 1391 were incredibly bloody: in Seville, hundreds of Jews were killed the synagogue completely destroyed and there were similar numbers of victims in other cities, such as Cordoba, Valencia and Barcelona

The Jewish Population

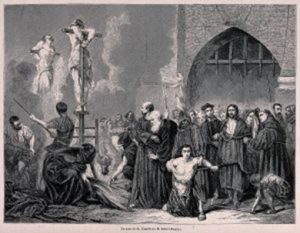

Wood engraving by Bocort after H.D. Linton

Towards the end of the 15th century, the Reconquista was drawing to an end, nearly finished, however, the desire for religious unity became more of a pervasive force.. Spain’s Jewish population, amongst the largest in Europe became a target.

Over the centuries, the Jewish communites throughout Spain had flourished and grown in numbers and strength , despite anti-Semitism surfacing from time to time. During the reign of Henry III of Castile and Leon (1390–1406), Jews faced increased persecution and were pressured to convert to Christianity. The pogroms of 1391 were especially brutal, and the threat of violence hung over the Jewish community in Spain. Faced with the choice between baptism and death, many converted and many others were killed. Those who adopted Christian beliefs—the so-called conversos (Spanish: “converted”)—faced continued suspicion and prejudice.

Conversos

One of the consequences of these disturbances was the massive conversion of Jews. Prior to this, conversions were rare, motivated more by social than religious reasons. From the fifteenth century a new social group appeared: conversos, also called new Christians, distrusted by Jews and Christians alike. By converting, not only could Jews escape eventual persecution, but also obtain entry into many offices and posts prohibited to Jews be means of new, more severe regulations.

Many conversos attained important positions in fifteenth century Spain. Among them, physicians Andres Laguna and Francisco Lopez Villalobos (Ferdinand’s Court physician), writers Juan del Enzina, Juan de Mena, Diego de Valera and Alonso de Palencia, and bankers Luis de Santangel and Gabriel Sanchez (who financed the voyage of Christopher Columbus) were all conversos. Conversos face much opposition but managed to attain high positions in the ecclesiastical hierarchy, at times becoming severe attackers of Judaism. Some received titles of nobility and as a result, during the following century it was claimed that virtually all Spanish nobility descended from Jews.

Inquisition Begins

Alonso de Hojeda, a Dominican from Seville, convinced Queen Isabel that crypto-Judaism existed among Andalusian conversos during her stay in Seville between 1477 and 1478. A report, produced at the request of the monarchs by Pedro González de Mendoza, archbishop of Seville and by the Segovian Dominican Tomás de Torquemada, confirmed this allegation. The monarchs decided to introduce the Inquisition to uncover and do away with false converts requesting the Pope’s assent. On November 1, 1478, Pope Sixtus IV spread the bull Exigit sinceras devotionis affectus, establishing the Inquisition in the Kingdom of Castile. The bull gave monarchs exclusive authority to name the inquisitors. However, the first two inquisitors, Miguel de Morillo and Juan de San Martín were not named until two years later, on September 27, 1480 in Medina del Campo.

At first, the activity of the Inquisition was limited to the dioceses of Seville and Cordoba, where Alonso de Hojeda had detected converso activity. The first Auto de Fé was celebrated in Seville on February 6, 1481, where six people were burned alive. Alonso de Hojeda gave the sermon himself and following this the Inquisition grew rapidly. By 1492, tribunals existed in eight Castilian cities: Ávila, Cordoba, Jaén, Medina del Campo, Segovia, Sigüenza, Toledo and Valladolid.

Establishing the new Inquisition in the Kingdom of Aragón was more difficult, the population of Aragón being adamantly opposed to the Inquisition. Ferdinand did not resort to placing new appointments; rather he breathed new life into the old Pontifical Inquisition, submitting it to his direct control. In addition, differences between Ferdinand and Sixtus IV prompted the latter to spread a new bull downright prohibiting the Inquisition’s extension to Aragon. In this bull, the Pope unambiguously criticized the procedures of the inquisitorial court.

The cities of Aragón continued to resist, and even saw periods of revolt, for instance in Teruel from 1484 to 1485. However, the murder of the inquisidor Pedro Arbués in Zaragoza on September 15, 1485, caused public opinion to turn against the conversos in favor of the Inquisition. Pedro Arbués was an official of the Spanish Inquisition who was assassinated in the La Seo Cathedral of Zaragoza in an alleged plot by conversos and Jews. He was quickly venerated as a saint by popular acclaim, and his death greatly assisted the Inquisition and its Inquisitor General, Tomás de Torquemada, in their campaign against heresy and crypto-Judaism. In Aragón, the inquisitorial courts focused specifically on members of the powerful converso minority, ending their influence in the Aragonese administration. Between the years 1480 and 1530, the Inquisition saw a period of intense activity. The exact number of trails and executions is debated, but it is said to be approximately 2,000 people.

Expulsion Of The Jews

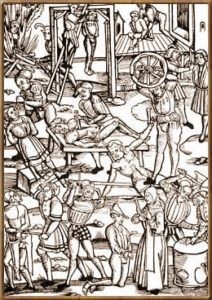

A 1508 woodcut of the Inquisition

Jews who continued practicing their religion were not persecuted by the Holy Office, however, it was suspicious of them because it was thought that they urged conversos to practice their former faith. In the trial at Santo Niño de la Guardia in 1491, two Jews and six conversos were fated to be burned for practicing an allegedly sacrilegious ritual.

March 31, 1492, only three months after the reconquest, concluded with the fall of Granada, Ferdinand and Isabella publicized a decree ordering the expulsion of Jews from all their kingdoms. Jewish subjects were given until July 31, 1492 to choose between accepting baptism and leaving the country. Although they were allowed to take their possessions with them, land-holdings, of course, had to be sold. Gold, silver and coined money were surrendered. The reason given to justify this order was that the proximity of unconverted Jews served as a reminder of their former faith and persuaded many conversos to relapsing and returning to the practice of Judaism.

The number of the Jews that left Spain is not recorded and therefore difficult to accurately estimate. Historians cite figures between 300 and 800,000. Nevertheless, more populist estimates are significantly lower. Henry Kamen, who wrote the book, “The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision, estimates that of a population of approximately 80,000 Jews, about one half or 40,000 chose emigration. The Spanish Jews emigrated mainly to Portugal, where they were later expelled in 1497 as well as to Morocco. Much later, the Sefardim, descendants of Spanish Jews, established thriving communities in many cities of Europe, North Africa and mainly in the Ottoman Empire.

The most intense period of persecution of conversos lasted through 1530. From 1531 through 1560, the percentage of conversos among the Inquisition trials lowered significantly, down to 3% of the total. There was a rebirth of persecutions when a group of crypto-Jews were discovered in Quintanar de la Orden in 1588. The last decade of the sixteenth century saw a rise in denunciations of conversos. At the beginning of the seventeenth century some conversos who had fled to Portugal began to return to Spain, fleeing the persecution of the Portuguese Inquisition that was founded in 1532. This translated into a rapid increase in the trials of crypto-Jews, among them a number of important financiers. In 1691, during a number of Autos de Fe in Mallorca, 36 chuetas, or conversos of Mallorca, were burned.

Repression Of Moriscos

The Inquisition did not exclusively target Jewish conversos and Protestants. Moriscos, who were converts from Islam, suffered its rigors as well, although to a lesser degree. The moriscos were concentrated in the recently conquered kingdom of Granada, Aragon, and Valencia. Officially, all Muslims in Castile had been converted to Christianity in 1502; those residing in Aragon and Valencia were obliged to convert by Charles I’s decree of 1526.

In the first half of the century, many moriscos were under the jurisdiction of the nobility, so persecution would have been attacking the economic interests of this powerful social class. However, even though the moriscos were mostly ignored by the inquisition in the first half of the century, things changed in the second half of the century under Phillip II. Between 1568 and 1570, the revolt of the Alpujarras occurred, which was repressed with unusual harshness. Beginning in 1570, in the tribunals of Zaragoza, Valencia and Granada, morisco cases became much more abundant. In Aragon and Valencia moriscos formed the majority of the trials of the Inquisition during the same decade. In the tribunal of Granada itself, moriscos represented 82 percent of those accused between 1560 and 1571. However, the moriscos did not experience the same harshness as Jewish conversos and Protestants, and the number of capital punishments was proportionally less.

Cruelty To Protestants

During the sixteenth century, Protestant reformers bore the brunt of the Inquisition. Interestingly, a large percentage of Protestants were of Jewish origin.

The first target were members of a group known as the alumbrados of Guadalajara and Valladolid. The trials were time-consuming, and ended with prison sentences of different lengths. However, no executions took place. In the process, the Inquisition picked up on rumours of intellectuals and clerics who, interested in the Erasmian ideas, had allegedly strayed from orthodoxy. Juan de Valdés was forced to flee to Italy to escape the Inquisition, whilst the preacher, Juan de Ávila spent almost a year in prison.

The first trials against the Protestants influenced by the Reformation took place between 1558 and 1562 in Valladolid and Sevilleas, at the beginning of the reign of Philip II, against two communities of Protestants from these cities. These trials signaled a notable escalation of Inquisition activities. A number of enormous Autos de Fe (the ritual of public penance of condemned heretics and apostates) were held. Some of these were presided over by members of the royal family, and approximately one hundred people were executed. After 1562 the trials continued but the repression was reduced. It is estimated that only a dozen Spaniards were burned alive for Lutheranism through the end of the sixteenth century, although some 200 faced trial. The Autos de Fe of the mid-century virtually put an end to the largely diminished Spanish Protestant population.

Torture Methods

Torture was used only to get a confession and wasn’t meant to actually punish the accused heretic for his crimes. Some inquisitors used starvation, forced the accused to consume and hold vast quantities of water or other fluids, or heaped burning coals on parts of their body. But these methods didn’t always work fast enough for their liking.

Strappado is a form of torture that began with the Medieval Inquisition. In one version, the hands of the accused were tied behind his back and the rope looped over a brace in the ceiling of the chamber or attached to a pulley. Then the subject was raised until he was hanging from his arms. This caused the shoulders to pull out of their sockets. Sometimes, the torturers added a series of drops, jerking the subject up and down. Weights could be added to the ankles and feet to make the hanging even more painful.

The rack was another renowned torture method associated with the inquisition. The victim had his hands and feet tied or chained to rollers at one or both ends of a wooden or metal frame. The torturer turned the rollers with a handle, which pulled the chains or ropes in increments and stretched the subject’s joints, often until they dislocated. If the torturer continued turning the rollers, the accused’s arms and legs could be torn off. Often, witnessing someone going through this intense torture on the rack was painful enough to extract another person’s confession.

Whilst the accused heretics were on strappado or the rack, inquisitors often applied other torture devices to their bodies. These included heated metal pincers, thumbscrews, boots, or other devices designed to burn, pinch or otherwise mutilate their hands, feet or bodily opening. Although mutilation was technically forbidden, in 1256, Pope Alexander IV decreed that inquisitors could clear each other from any wrongdoing that they might have done during torture sessions.

Inquisitors needed to obtain a confession because they believed it was their duty to bring the accused back to the faith. A true confession resulted in the accused being forgiven, but he was usually still forced to clear himself by performing penances, such as pilgrimages or by wearing multiple, heavy crosses.

Inquisition torture chamber. Mémoires Historiques (1716)

If the accused didn’t confess, the inquisitors could sentence him to life imprisonment. Repeat offenders were people who confessed, then retracted their confessions and publicly returned to their sacrilegious ways. They could be ‘abandoned’ to the ‘secular arm.’ (what does this mean?)

Capital punishment allowed for burning at the stake. In some cases, accused heretics who had died before their final sentencing had their corpses or bones dug up, burned and cast out. The last inquisitorial act in Spain occurred in 1834, but all of the Inquisitions continued to have a lasting effect on Catholicism, Christianity and the world as a whole.