A Short History of Convict Australia

Short History of Convict Australia is the first ever documentary about Australia’s convict past. It visits the locations where convicts lived and worked, talks to historians and descendants of convicts and experiences the legacy of the dramatic, brutal birth of a nation.

This site is the number one resource for those who want to know more about Convict Australia, and the locations where Australian history actually happened. Containing facts, figures, and relevant footage from the documentary, it’s an educational experience.

Who Were the Convicts?

The late 18th century was a period of immense social and political change. France was reeling from revolution and America had just gained her independence.

In Britain the industrial revolution had driven thousands of poverty-stricken country folk to the cities. As a new underclass dependent on crime emerged, the prisons were overflowing and the hangman had his work cut out dealing with the perpetrators of serious offences.

In 1787 the establishment urgently needed a new solution to the problem of the burgeoning prison population.

The botanist from Captain Cook’s discovery expedition 18 years earlier eventually hit upon the idea of Botany Bay, Australia. It wasn’t the ideal choice because the place had only been glimpsed once and the 15,000 mile voyage would take more than 8 months.

Nevertheless, between 1788 and 1868 165,000 British and Irish convicts made the arduous journey to an unknown land we now call Australia.

The majority of the 165,000 convicts transported to Australia were poor and illiterate, victims of the Poor Laws and social conditions in Georgian England. Eight out of ten prisoners were convicted for larceny of some description.

However, apart from unskilled and semi-skilled labourers from Britain and Ireland, transportees came from astonishingly varied ethnic backgrounds: American, Corsican, French, Hong Kong, Chinese, West Indian, Indian, and African.

There were political prisoners and prisoners of war, as well as a motley collection of professionals such as lawyers, surgeons and teachers.

The average age of a transportee was 26, and their number included children who were either convicted of crimes or were making the journey with their mothers. Just one in six transportees was a woman.

Depending on the offence, for the first 40 years of transportation convicts were sentenced to terms of seven years, 10 years, or life.

Transportation

When prisoners were condemned to transportation, they knew there was little chance they’d see their homeland, or their loved ones again. Even if they survived the long, cruel journey they didn’t really know what fate awaited them in a land on the other side of the world.

Relatively few convicts returned home – partly because the system of reprieves extended to so few and partly because they tended to settle in Australia. Three quarters of the convicts were unmarried when they left home, so those who found a partner during the voyage or once they arrived in Australia weren’t likely to leave them behind.

Nevertheless, transportation was a terrifying prospect. As they awaited their fate, prisoners were detained in the rotting hulks of old warships, transformed into makeshift prisons and rammed up against the mud at Portsmouth Harbour and London’s Royal Docklands.

Hulks and love tokens

Holed up in the hulks awaiting the dreaded voyage to begin, it was common practice for transportees to spent their days engraving love-tokens which they would give as last mementoes to friends and relatives. Many used the 1797 copper cartwheel penny, and the inscriptions range from just the name and date of deportation to elaborate poems and etchings of convicts in chains and boats. Professional engravers were even allowed on board the hulks, and prisoners would commission them to craft a poignant keepsake on their behalf.

The Voyage

The journey was long and hard. For the first 20 years, prisoners were chained up for the entire 8 months at sea. The cells were divided into compartments by wooden or iron bars. On some ships as many as 50 convicts were crammed into one compartment.

Discipline was brutal, and the officers themselves were often illiterate, drunken and cruel. Their crews were recruited from waterside taverns. They were hardened thugs who wouldn’t shrink from imposing the toughest punishment on a convict who broke the rules.

Disease, scurvy and sea-sickness were rife. Although only 39 of the 759 convicts on the first fleet died, conditions deteriorated. By the year 1800 one in 10 prisoners died during the voyage. Many convicts related loosing up to 10 teeth due to scurvy, and outbreaks of dysentery made conditions foul in the confined space below deck.

Convict ships transporting women inevitably became floating brothels, and women were subjected to varying degrees of degradation. In fact, in 1817 a British judge acknowledged that it was accepted that the younger women be taken to the cabins of the officers each night, or thrown in with the crew.

Australia Day

The first fleet entered Botany Bay in January 1788. On arrival, however, the bay was deemed unsuitable and the transportation tarried 9 miles north, landing at Sydney Cove six days later.

The night the male convicts were landed, January 26th 1788, the Union Jack was hoisted, toasts were drunk and a succession of volleys were fired as Captain Arthur Philips and his officers gave three cheers.

Australia Day is an annual celebration commemorating the first landing of white settlers in Australia. These days there’s fireworks, parades, arts, crafts, food and family entertainment. It’s seen as a celebration of Australian culture and way of life.

For those convicts who disembarked in Sydney Cove in 1788, however, the first Australia Day was a bewildering experience. Unused to their land legs, they stumbled cursing through the uncultivated wood in which they had landed. It was two weeks before enough tents huts had been constructed for the female convicts to disembark, and in the midst of a gale they held the first bush party in Australia – dancing, singing and drinking while the storm raged and couples wedged themselves between the red, slimy rocks.

The Aborigines

The aboriginal people had lived in Australia undisturbed by white men for sixty thousand years before the arrival of the first fleet. For them, the arrival of the convicts was catastrophic.

Their first encounter with their new neighbours was the sight of one huge orgy on the beach. Nevertheless, at first the Aborigines pitied the prisoners and couldn’t understand the cruelty of the soldiers towards them. Gradually the convicts began to resent the rations and clothing the Aborigines received, and they took to stealing their tools and weapons to sell to the sailors as souvenirs.

In May 1788 a convict was found speared in the bush and a week later two more were murdered. Between 2000 and 2500 Europeans and more than 20,000 Aborigines were killed in conflicts between convicts and aborigines.

The convicts felt the need to establish a class below themselves. Australian racism towards the Aboriginal people originated from the convicts and gradually percolated up through society. This marked the beginning of a bitter, painful battle for the survival of Aboriginal culture which has raged for than 200 years.

Convict Life

A convict’s life was neither easy nor pleasant. The work was hard, accommodation rough and ready and the food none too palatable. Nevertheless the sense of community offered small comforts when convicts met up with their mates from the hulks back home, or others who had been transported on the same ship.

Convict Work

Male convicts were brought ashore a day or so after their convoy landed arrival. They were marched up to the Government Lumber Yard, where they were stripped, washed, inspected and had their vital statistics recorded.

If convicts were skilled, for example carpenters, blacksmiths or stonemasons, they may have been retained and employed on the government works programme. Otherwise they were assigned to labouring work or given over to property owners, merchant or farmers who may once have been convicts themselves

Convict Diet:

A convict’s daily rations were by no means substantial. Typically, they would consist of:

Breakfast: A roll and a bowl of skilly, a porridge-like dish made from oatmeal, water, and if they were lucky, scrapings meat.

Lunch: A large bread roll and a pound of dried, salted meat.

Dinner: One bread roll and, if they were lucky, a cup of tea.

As if this wasn’t enough to turn your stomach, the officials had an unpleasant cure for hangovers and drunkenness, which they imposed on convicts who were overly fond of rum. The ‘patient’ was forced to drink a quart of warm water containing a wine-glass full of spirits and five grains of tartar emetic. He was then carried to a darkened room, in the centre of which was a large drum onto which he was fastened. The drum was revolved rapidly, which made the patient violently sick. He was then put to bed, supposedly disgusted by the smell of spirits!

Convict Clothing

Until 1810 convicts were permitted to wear ordinary civilian clothes in Australia. The new Governor, Lachlan Macquarie, wanted to set the convicts apart from the increasing numbers of free settlers who were flocking to Australia.

The distinctive new uniform marked out the convicts very clearly. The trousers were marked with the letters PB, for Prison Barracks. They were buttoned down the sides of the legs, which meant they could be removed over a pair of leg irons.

Convict Class System

A class system evolved amidst the convict community. The native born children of convict couples were known as ‘currency’, whereas the children of officials were known as ‘sterling’.

A wealthy class of ‘Emancipists’ (former convicts) sprung up when the Governor began to integrate reformed convicts to the fledgling society. These Emancipists, who often employed convicts in their turn, were very much despised by the soldiers and free-exclusives who had come to Australia of their own free will.

Convict Housing

For those convicts who remained in Sydney, lodgings were available in a neighbourhood calledThe Rocks. It was a fairly free community with few restrictions on daily life. Here, husbands and wives could be assigned to each other and some businesses were even opened by convicts still under sentence.

The Rocks became notorious for drunkenness, prostitution, filth and thieving, and in 1819 Governor MacQuarie built Hyde Park Barracks, which afforded greater security.

Those sent to work in other towns or in the bush were often given food and lodging by their employer. The road projects and penal colonies offered far less comfortable accommodation, often with 20 sweaty bodies crammed into a small hut.

Tattoos

When convicts arrived in Australia, detailed reports were compiled of their physical appearance, including distinguishing marks. At the beginning of the 19th century one in four convicts was tattooed, and although it’s hard for us to fully understand what these may have meant to the individual, some are interesting, even witty comments on convict life.

Some tattoos appear to be poignant love tokens and permanent reminders of the life and loved ones they left behind.

Some are cheeky remonstrations with the officials, such as the words ‘Strike me fair, stand firm and do your duty‘.

Similarly, a crucifix tattooed on a convict’s back would give that impression that Christ himself was being flogged, and angels were standing by with a cup to catch the blood. This implies that it is the authorities that are sinful.

Convict Women

Women made up 15% of the convict population. They are reported to have been low-class women, foul mouthed and with loose morals. Nevertheless they were told to dress in clothes from London and lined up for inspection so that the officers could take their pick of the prettiest.

Until they were assigned work, women were taken to the Female Factories, where they performed menial tasks like making clothes or toiling over wash-tubs. It was also the place where women were sent as a punishment for misbehaving, if they were pregnant or had illegitimate children.

Other punishments for women include an iron collar fastened round the neck, or having her head shaved as a mark of disgrace. Often these punishments were for moral misdemeanours, such as being ‘found in the yard of an inn in an indecent posture for an immoral purpose‘, or ‘misconduct in being in a brothel with her mistress’ child‘.

As women were a scarcity in the colony, if they married they could be assigned to free settlers. Often, desperate men would go looking for a wife at the Female Factories.

Pardon and Punishment

Tickets of leave were normally granted after four years for those with a seven-year sentence, six years for a fourteen-year sentence and eight-years for life. The principal superintendent looked at the applications and depending on how much extra punishment the prisoner had received he’d make a decision to recommend the ticket or not.

A ticket of leave would exempt convict from public labour and allow them to work for themselves.

After this a prisoner may receive conditional pardon, which meant he was free but had to stay in Australia, or absolute pardon, which meant he was free to return to England.

If a prisoner was uncooperative or committed further crimes there was an equally well defined scale of punishments he would receive: first working on a road gang, then being sent to a penal colony, and finally capital punishment.

There were also a number of incidental punishments a prisoner could receive: flogging, solitary confinement, treadmill, the stocks, food depravation and thumbscrews.

Flogging

A prisoner had to be sentenced to flogging by a magistrate. There would be a scourger present, a surgeon and a drummer to count the beats. Often floggings were carried out in public, as a warning to other convicts not to commit the same offence.

There are Australians alive today who remember the horrific scars borne by their grandparents as a result of brutal floggings.

On Norfolk Island an instrument called a cat’o nine tails was used to flog the convicts. This was a whip made of leather strands, with a piece of lead attached to each thong. The lead would tear deep into the flesh with each stroke, and the only effective relief from the agony it inflicted was to urinate on the ground then lie the open wounds on it.

Australian Penal Colonies

The conditions in the penal colonies were exceptionally harsh. Prisoners who re-offended were sent to the colonies, and it was unlikely they’d ever be freed under the system of reprieves.

Macquarie Harbour Penal Station

The natural prison built in the middle of Macquarie Harbour, known as Sarah Island, was meant to be escape proof. It was surrounded by impenetrable rainforest and very few escape attempts were recorded.

The convicts who were sent to Sarah Island were often escapees from other penal colonies. Others were skilled men whose task it was to build ships.

The convicts were cut down the massive Huen Pines, lash the logs together and raft them down the river. They would work twelve hours a day in freezing cold water, in leg-irons, under the continual scrutiny of the guards. Not surprisingly their main objective was escape.

Norfolk Island

Fifteen hundred miles off the coast of New South Wales was the most brutal prison of the convict period. Its name was Norfolk Island. The British wanted an institution that would act as a deterrent in the colony, which would terrify even those in Britain who heard its name.

Sir Thomas Brisbane wrote ‘I wish it to be understood that the felon who is sent there is forever excluded from all hope of return‘.

Indeed a high number of prisoners preferred suicide to enduring the abominable conditions. Others poisoned, burned or blinded themselves in attempts to avoid work. Their physical and mental health suffered due to interminable hard labour, poor diet, overcrowding, coarse, uncomfortable clothing and harsh punishments such as flogging with a cat’o nine tails and being chained to the floor.

The men lived forever in the shadow of the ‘Murderers Mound’, where twelve of the convicts who participated in an uprising in July 1846 were executed. Tales from Norfolk Island filtered back to the England and the colony was eventually abandoned in 1855.

Port Arthur

After the closure of Norfolk Island, offenders were sent to the southern tip of Tasmania, to a colony called Port Arthur.

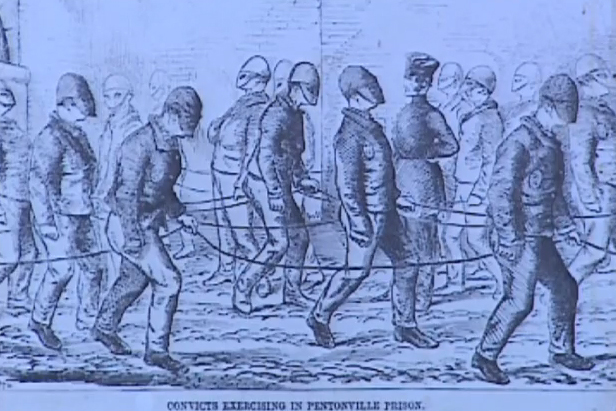

Prison reformers back in Britain wanted to experiment with new forms of punishment. The centrepiece of the new institution was the Model Prison.

The idea was to replace flogging and corporal punishment with complete sensory deprivation, which would break their spirit and turn them into good citizens. The guards wore slippers and carpets in the hallways deadened all sounds. When the convicts were allowed out of their cells, they were made to wear masks to they couldn’t recognise one another. There was very little verbal communication.

If you’re going to escape from prison, Australia’s hardly the easiest place to hitch a ride home from. Nonetheless, theres some incredible tales of the few who made a break for it.

John Donahue and the bushrangers

Bushrangers are seen as heroes in Australia, representing rebellion and and triumph over authority. The most celebrated bushranger of them all was John Donahue, a young Dubliner who was sentenced to transportation for life in 1823.

After his escape he roamed the bush, besieging the settlers and living off a life of plunger. He used to hang out in the caves near Picton.

John Donahue was eventually shot dead in 1830 by a policeman and his tale is immortalised in the Ballad of Bold Jack, banned at the time as a treason song.

Sarah Island

The penal colony at Sarah Island was meant to have been impossible to escape from. More than 180 escape attempts are known to have been made but few were successful: most escapees perished in the rainforest and many returned voluntarily after a few days.

Some did make it. Alexander Pearce escaped Sarah Island twice, and only survived by eating his companions. He later told his companions that he preferred human flesh to normal food.

Another great tale is of the convicts who stole the Cyprus, a supply vessel carrying a group of convicts to Macquarie Harbour. They seized the vessel on route, dumped the officers and crew on shore and sailed off to Japan where they pretended to be ship wrecked British mariners. They were sent all the way back to Britain as poor starving shipwrecked sailors. Unfortunately one of them was strolling through London town when who should he meet but the ex-police constable from Hobart town who recognised his tattoos.

William Buckley escaped from Sorrento in Victoria in 1803. He spent 30 years living with the aborigines and wore a long beard and kangaroo skins. When he returned to civilisation he had completely forgot the English language and had to learn to speak again. He was completely pardoned and became a respected civil servant.