Gladiators of Rome: Fight to the Death

One of the most powerful empires in the history of the world, Ancient Rome at it’s most glorious controlled about half of Europe, the North Coast of Africa and quite a bit of the Middle East. Defeated in 476 AD, the Empire might not have lasted, but it’s ruins remain and in a modern world you can still walk in it’s ancient footsteps…

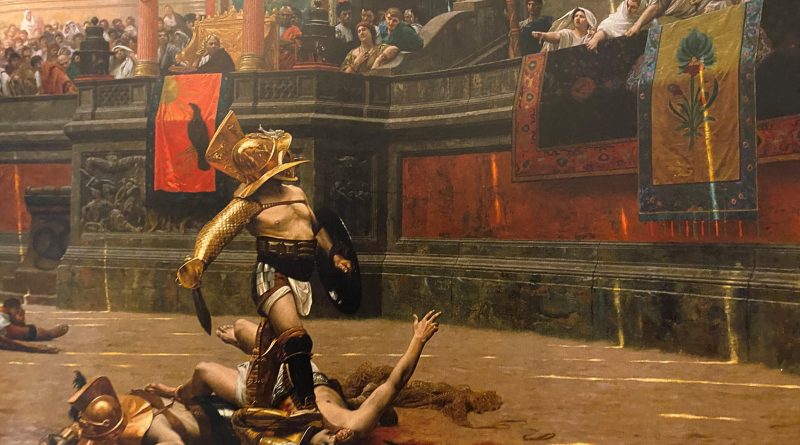

Gladiatorial Games are amongst the most enduring images we have of the Roman Empire. Often accompanied by grand processions, fights between wild beasts and chariot racing, it was two gladiators fighting it out to the death that drew the loudest screams of delight from the blood hungry crowds.

Gladiator fights originated as a sacrifice of blood to the dead. They were introduced to Rome in 264 BC when the sons of Junius Brutus honoured their dead father by matching three pairs of gladiators. They fought for nine days and the ninth day marked the end of the period of mourning.

This funereal ritual became so popular that a few years later it transferred to a bigger stage and soon Roman Emperors sponsored huge events that made gladiatorial games the biggest spectator sport in the Roman Empire.

Acquincum, Budapest, Hungary

Acquincum near Budapest was a Roman military town and you can still visit well preserved ruins of baths, barracks and a forum. But, best of all, several times a year a re-enactment society called Collegium Gladitorium recreate all aspects of the gladiatorial games in and around this ruined amphitheatre.

The gladiators were primarily criminals, slaves and prisoners of war from all over the Empire who were trained to fight each other or animals generally until death.

The day before a fight the gladiators would tuck into a coena libera – a public banquet. For many it was the equivalent of the condemned mans last meal.

They wouldn’t have had the infamous delicacies that the Romans enjoyed – doormice, flamingo tongues and the like. Gladiators would have had a much simpler diet – whatever was cheap and available – bread, mushrooms, honey. But they did drink plenty of wine – it helped them forget what was coming the next day.

In Roman times they thought fennel made you immortal so the gladiators ate it before each fight.

The night before the games a the gladiators would have slept on the floor in cells beneath the amphitheatre – you can still see the ruined cells in some amphitheatres like the Colloseum in Rome- cramped, no room, dark.

In the morning of the games Gladiators known as bestiarii would fight exotic animals – lions, elephants, rhinos, hippos, captured in the Empire. The animals were abused and starved before the match to ensure they attacked their opponent and if the Emperor had taken a particular dislike to a contestant he might set two or even three beasts against the man at one time. Only poor fighters fought animals – the gladiators almost always won and there was little glory involved

It was not unusual to see 20 elephants killed in one day and some animals became extinct during this time – such as elephants in North Africa and lions in Mesopotania.

The main fights took place in the afternoon. There were three main types of gladiators who generally fought in couples – with one type pitted against a different type.

A Thraex fought with fork and dagger.He wore a subligaculum, a loin cloth held up by a sword belt or balteus. His legs were protected by metal half cylinders called ocreae. He also wore a manica, a sort of leather sleeve reinforced by metal scales.

A Samnite fought with a curved shield and sword wearing only an ocreae on his left leg and fasciae, leather bands, on his wrists and a masked helmet.

A Retiarius fought with a net and a trident

He had no armour and his chief means of defence was attack.

The first ‘warm up’ fights used wooden weapons. As the games progressed the weapons became more deadly. In fact the fights were so serious that swords and daggers would be given to the Emperor to test their sharpness.

Professional gladiators lived in schools where they underwent a rigorous training programme. They learnt how to face death and fight bravely: there was nothing more degrading than to run away.

The chances of a gladiator surviving any one fight were slim – about 1 in 10. During the Colosseum’s opening in AD 80 spectacular games were held for 100 days in which hundreds of animals and on one day alone 2,000 gladiators were killed. The largest ever gladiatorial combat involved 4,941 pairs battling it out more often than not to the death.

One clue as to the popularity of the gladiators is the amount of amphitheatres there are spotted over Europe and North Africa. There’s over 350 of their ruined remains and this is the most famous is the Colosseum in Rome.

As popular as they were gruesome – if an Emperor threw lavish games he kept his people happy. They showed strength which was important for a warring and aggressive Empire.

There were over 50,000 people in the audience in some arenas .The noise was deafening. There was an orchestra who played music in between fights.

Before the fights gladiators and animals were kept in cells beneath the arena: you can still see them today. A wooden platform operated by weights and pullies – a sort of ancient elevator – brought the animals and gladiators up into the arena.

Nero loved female gladiators, especially the ones who fought topless! Then there was Domitian who insisted on women fighting dwarves.

Cowardice wasn’t tolerated. When a gladiator begged for mercy if the crowd thought he had fought a good fight they would raise their thumbs and he would be spared, if they didn’t they would lower their thumbs and he would be killed.

When a gladiator was killed an official would come on dressed as Charon – a beaked demon from the underworld. He would check if they were really dead by poking them with a red hot iron, and while the trumpets played the body was dragged out of the arena.

The grand prize was to come back and fight another time! Chances of survival were slim. The winner of a fight was given a prize usually gold or a trinket . . If you saved up enough money and had a popular following and were very lucky you might buy your freedom.

In Rome, there’s history on every corner – from Celian Hill where they kept the animals who fought at the Colosseum. To Circus Maximus where they held the chariot races.

Chariot Racing, which often accompanied gladiatorial games, was the other major spectator sport that set the Roman publics’ pulses racing.

Although not as gory as the gladiator fights, Chariot racing was a real crowd pleaser. Much like today the crowds betted heavily on the horses. During the races perfumed water was sprinkled over the crowd to refresh them as it got very hot and dusty. Unlike in the gladiatorial games, men and women could sit together. In fact it was where a lot of courting couples went – a bit like the back row of the cinema!

The crowd at an Italian football game really resembles the one at the chariot races. At a soccer match today each team here has its own colours – Roma is red, Lazio is blue. At a chariot race there would have been four teams. Each team had it’s own colour – red, green, blue, white and spectators would have a certain colour team that they cheered on. Today, Roma’s fans are more working class while Lazio’s are more intellectual. Back then the colours reflected more than the team, but represented social class and there were often conflicts between rival groups outside the arena.

Back in ancient times crowds coming to gladiatorial games or chariot races were controlled by a system of numbering tickets to match gate numbers to ramps leading to various levels. It works exactly the same way at a soccer match today.

In the North of Italy in Valle D’Aosta each year here they hold a massive Roman Carnival which culminates with a chariot race around the town. Everyone is dressed in Roman costume – either ta senator, a gladiator, otr a legionnaire….

Very few people became gladiators by choice – it was so dangerous. However more voluntarily became chariot racers – their chance of survival was much higher and winners were famous – the pop stars of the day.

In ancient times they would have raced seven laps of an oval arena – approximately 4 miles in total. Turns were sharp and there were often horrible accidents when racers and horses were killed. When a chariot was overturned it was known as being ‘shipwrecked’ – the highlight of the race for the crowd.

Capua

Capua homed Italy’s second largest amphitheatre after the Colosseum. While chariot racing was a popular form of entertainment here, it was for an altogether bloodier form of entertainment for which it was best known….. Capua was full to the gills of barracks – it was a city of gladiators. It housed the largest training school for gladiators in the Roman Empire.

Its here that we have the first evidence of a uprising against gladiatorial games. Throughout the history of the Empire, certain sections of the population held an ambivalence towards what they regarded as a grotesque spectacle. It is here at Capua that we find the story of a Libyan prisoner of war turned gladiator called Spartacus who was to lead a famous slave revolt.

The schools were more like prisons and you can still explore the cells where the gladiators were incarcarated.

Oh yes, look at these cells – there are rows and rows of them without windows or skylights. There would have been about 1,000 gladiators living here – it would have been very cramped.

These fetters were founnd here – they would have presented the gladiators from standing upright. Recruits were drawn from all over the Empire and spoke different languages keeping them isolated from one another.

On arrival at the school or ludus as it was called they would be forced to swear on oath to submit to the branding iron, the whip and death by the sword. It was intended to nip in the bud any tendency of rebellion which was bound to arise when one of these men became aware of the harshness and injustice of the life they were to lead. The training regime was mercilessly rigourous – they trained systematically from dusk till dawn until they were ready to fight.

Slave Revolt

In AD 73 Spartacus escaped with 80 comrades and hid on Mount Vesuvius. He raised a army of 70,000 slaves and they defeated several Roman expeditions. They were finally defeated and Spartacus was killed.

Why is Spartacus so important considering his rebellion failed?

Well, firstly he stands for rebellion against injustice. He was the right who stood up against might. Secondly, even though his rebellion was crushed it did change Roman attitudes to slavery which was seen as potentially troublesome and gradually phased out.

When the rebellion was finally crushed 6000 of Spartacus’ men were crucified along this road – the 132 mile ancient Via Appia which leads to Rome as a warning to other gladiators with rebellious tendencies. It would be over 300 years before gladiatorial games were surpessed.

You can still see ancient tombs dating from the 1st century AD lining this road. And the Church of Domine Quo Vadis is where Jesus supposedly met Peter on his way out of Rome. A reminder that the popularity of gladiators coincided with the birth of Christianity.

Which brings me back to Rome and here to the Vatican City.

Nero’s Circo Vaticano once stood on the site where Saint Peters Basilica now stands. The body of the Saint was built in an anonymous grave there and his fellow Christians built a red wall to honour him. In 315 Constantine the first Christian Emperor ordered the construction of a basilica on the site.

They disapproved. As Christianity spread more people turned against the games and they began to loose their popularity.

Did they really throw Christians to the lions?

No, at least there is no evidence at all to support this. But they did throw some unarmed criminals to confront wild beasts who would tear them apart.

The magnificent Colosseum remained a venue for bloodshed until 404 AD when the Gladiatorial games finally stopped after a monk Telemachus rushed into the arena to separate two gladiators only to be stoned to death by the spectators. Afterwards the Emperor Honorius issued an edict banning the spectacles.

2000 years on and crowds still enjoy two people knocking the stuffing out of each other. Gladiatorial Games lasted six centuries and cost hundreds of thousands of lives to provide what Seneca called ‘a round robin of death’. They were a bloodthirsty lot the Romans. Modern day wrestling remains a popular sport all over the world, but thankfully nowadays it’s rather less dangerous.