The Mahdi Wars of Sudan

Britain’s strategic interest in Egypt increased after the construction of the Suez Canal. Opened in 1869, the Canal considerably shortened the trade and military routes to India and the East. In 1875, the British government bought shares in the Suez Canal Company.

Egypt, which owed nominal allegiance to the Ottoman sultan, had become virtually bankrupt by 1878. The dire economic situation led to Britain and France taking control of Egyptian finances and, in effect, running the country.

This caused outrage among large numbers of Egyptians. Their anger was exacerbated by the decision of their ruler, the Khedive (Viceroy), to get rid of many Egyptian Army officers as a money-saving measure. Many Egyptians also sought wider reforms that would increase opportunities for previously excluded groups.

Mahdist Rising

In occupying Egypt, Britain had also assumed responsibility for the Egyptian Sudan. An Islamic revolt had begun there in 1881, led by Mohammed Ahmed, who styled himself the ‘Mahdi’ or ‘guide’.

By the end of 1882, the Mahdists controlled much of the Sudan. And on 5 November 1883, at El Obeid, they annihilated an Egyptian force that had been sent to restore order.

General Gordon

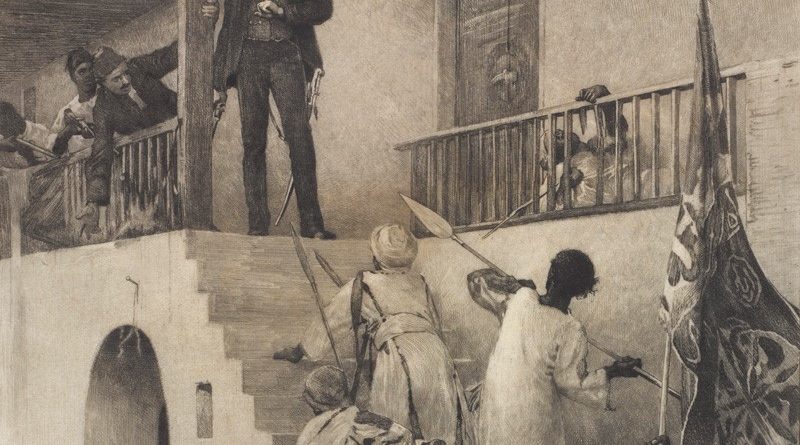

Meanwhile, Major-General Charles Gordon had been sent to Khartoum with orders to oversee the evacuation of the Sudan. Instead, he elected to stay and defend the Sudanese capital.

In Egypt slavery had become an anachronism, but a large portion of the Sudanese economy was still based on it. Gordon promptly set out to fulfill the terms of the treaty, and he broke up slave markets and imprisoned traders. Gordon’s campaign triggered a crisis in the Sudan’s economy, and the Sudanese soon came to believe that the crusade, led by European Christians, violated the principles and traditions of Islam. By 1879 Gordon’s actions had triggered a harsh backlash throughout the country. It was against this backdrop that the Mahdist movement was born.

In May 1884, Khartoum was invaded by the Mahdi and Britain was forced to organise a relief expedition to rescue Gordon.

The column finally reached Khartoum on 28 January 1885, two days after Gordon had been killed and the town had fallen.

Humiliation

For Britain, the death of Gordon at Khartoum was a national humiliation. There was strong public pressure on the government to send an expedition to avenge him and restore Egyptian rule.

A Mahdist invasion of Egypt was defeated during 1888-89. But it was not until 1896 that the government authorised military action. This decision may have been influenced by concerns that if Britain did not conquer the Sudan, then the Italians and French would.

Re-conquest

In 1896, an Anglo-Egyptian army, led by Major-General Herbert Kitchener, entered the Sudan. Kitchener understood the importance of keeping his force supplied, and he built a railway as he advanced and used steamers to move his troops and equipment down the River Nile. Progressing slowly but surely, he inflicted a number of defeats on the Mahdists.

On 8 April 1898, Kitchener’s force of about 12,000 attacked the fortified camp of a Mahdist army at Atbara. After a fierce struggle, the tribesmen were completely routed. Their commander, Emir Mahmud, and 4,000 of his men were captured.

Omdurman

Finally, on 2 September 1898, at Omdurman, Kitchener inflicted a crushing defeat on the forces of the Khalifa, Abdullah Ibn-Mohammed, who was the successor to the Mahdi.

Although they attacked with fanatical bravery, the Mahdists were no match for the rifles and Maxim machine guns of Kitchener’s army. By the end of the day, they had suffered approximately 27,000 casualties. The Anglo-Egyptians lost only 43 dead.

The Battle of Omdurman broke the power of the Mahdists. And although the Khalifa remained at large until the following November, the Sudan was quickly pacified.

Ultimately, Britain won the Mahdist War. It secured control over Sudan as a colony for over fifty years after Britain defeated the Mahdists.