Great British Artists: JMW Turner

Joseph Mallord William Turner, now regarded as a national treasure, was denounced as much as he was lauded during his lifetime.

Turner’s father, was a barber and wig maker in London’s Covent Garden. Recognising his son’s talent early on, William proudly displayed his son’s drawings around his shop, where they were seen by visiting gentlemen and dandies. As his success grew, the younger Turner eventually began to move in upper-class circles. But he remained proud of his roots, never dropping his Cockney accent or hiding his past.

Turner was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools in 1789, aged just 14. His progression was swift: Turner copied casts of ancient sculptures before moving on to life drawing and reproducing the Old Masters, which were firm foundations for his later, revolutionary work. To fund his education, Turner worked as an architectural draughtsman and painted scenery for London playhouses, activities which led him to develop both exceptional technical skill and a taste for landscapes.

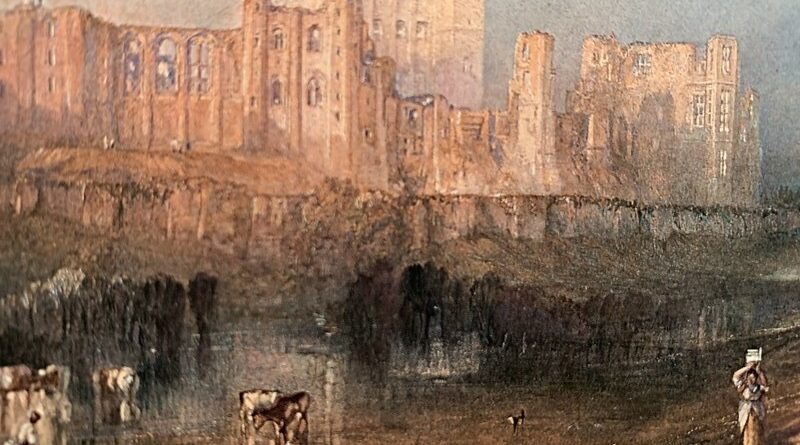

Kenilworth Castle by Turner

Soon a consortium of businessmen provided the artist with a coach and guide, enabling him to travel to Paris to study paintings in the Louvre and to sketch landscapes throughout the Alps. The mountainous landscape had a lasting impact on his career, inspiring a lifetime of visits.

By 1804, when he was just 29 years old, Turner had opened his own gallery in London’s Harley Street, where he displayed both his early ambitious atmospheric landscapes and smaller, more intimate English pastoral scenes. This unorthodox, self-promoting approach proved a hit with important collectors, who offered Turner the run of their stately homes. Upon visiting the Harley Street gallery, the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova declared Turner a genius.

Later in life, Turner published volumes of his works that became popular with a newly minted bourgeoisie, capitalising on a mass market that was changing the nature of collecting and exhibiting. In time Turner became preoccupied with his own artistic legacy, attempting to buy back works and arranging for his personal collection to be housed at London’s newly opened National Gallery.

Senior Academicians, esteemed tastemakers and even the Prince Regent often found Turner to be hostile and pushy, and snubbed his work for debasing the Old Master tradition. Notes scrawled in his sketchbooks at the time reflect the bitterness provoked by these remarks. Ultimately, however, they pushed Turner to explore new artistic frontiers.

The Wreck of the Transport Ship by Turner

He began experimenting with unusual compositions, eschewing his brush in favour of a palette knife or even his thumb to scrape and smudge the surface of his works.

Famously solitary, Turner began spending more time at the lodge he had built in Twickenham, painting views of the Thames. He shared his home with his devoted father, a widower, who cooked, cleaned, gardened and prepared his oil paints and other materials.

Turner, who once wrote that, ‘Woman is doubtful love’, publicly denied being the father of two daughters born to a secret lover.

Beginning in the 1830s, Turner’s works took a darker turn. His scenes of Venice now presented the city as a decaying tourist trap. He painted the Houses of Parliament in flames, a scene he witnessed from a boat on the Thames. In 1839, he created perhaps his best-known work, The Fighting Temeraire, in which the grand gunship that played such a decisive role in the Battle of Trafalgar is drawn by tugboat to its final resting place, a scrapyard at London’s Rotherhithe Docks. Painted at the pinnacle of Turner’s career, the work highlighted his anxiety at the dawn of a new, industrial era. The crumbling majesty of the once-great ship represented human uncertainty in the face of modernity; a theme that prefigured the existentialist art movements of the 20th century.

In 1845 Turner was elected Acting President of the Royal Academy, but was forced to retire a year later due to ill health. His public appearances became rarer; when in London, he often donned a disguise and used a pseudonym. His dishevelled appearance and increasing paranoia permeated his later works, such as Sisteron from the North West, with a Low Sun, whose rough brushwork and muted palette would inspire the French Impressionists several decades later.

In search of healthy sea, air and solace, which he found in the company of a widow who became his mistress, Mrs Sophia Booth, Turner began regularly returning to the coastal town of Margate in Kent. There he completed some of his final works, drawing fishermen, sailors and tourists.

By 1851, Turner was bed-bound; he died on 19 December that year. Fittingly for the master painter of natural light, Turner was said to have been bathed in a flash of sunlight at the moment of his death. His body was interred at St. Paul’s Cathedral, where he had arranged to be buried alongside his ‘Brothers in Art’, Sir Joshua Reynolds and Sir Thomas Lawrence.

In 1862, a statue of Turner was erected in the cathedral, paid for with £1,000 earmarked in his will. The sculpture portrays him as a virile and proud hero of painting, a far cry from his bald, toothless and hollow-cheeked death mask.

The leading Victorian critic John Ruskin described Turner as the artist who could most ‘stirringly and truthfully measure the moods of nature’. By 1910 a wing of the National Gallery of British Art (now Tate Britain) housed his national bequest.

In 1984, the annual Turner Prize was named in his honour, and in 2011 the Turner Contemporary gallery opened in Margate, celebrating the association between the artist and the seaside town. In 2016, Turner’s image was chosen by the Bank of England to appear on the new £20 note, honouring his profound contribution to British art.

Written by Ian Cross, edited by Kaz Bosali