A Short History of Rubber

Originating from a tree found in the jungles of the Amazon, rubber was used in its raw form by indigenous tribes for centuries. But it wasn’t until “vulcanisation” was achieved by British and American scientists, that the commodity became truly useful. In the process it triggered a gold rush, changing the fortunes and lives of millions and the fate of nations.

Discovery

In May of 1526 Andrea Navagero, the Venetian ambassador to Spain, attended an entertainment in Seville staged for the royal court. Seven years earlier, Hernán Cortés, acting without the authorization of the Spanish throne, had invaded Mexico and toppled the Triple Alliance (Aztec Empire). The king and the queen had to decide what to do with their millions of new subjects. To demonstrate the intelligence, skills, and noble demeanour of the peoples of the Triple Alliance, the antislavery faction of the Spanish church had imported a group of them from Seville. The Indians divided into teams and played a showcase version of the Mesoamerican sport of ullamaliztli, which the Venetian ambassador attended.

He was mesmerized by ullamaliztli, which he seems to have thought was a performance akin to juggling act. In ullamaliztli, two squads vied to drive a ball through hoops on the opposite ends of a field – an early version of soccer, one might say, except that the ball was never supposed to touch the ground and the players could hit it only with their hips, chests and thighs.

As fascinating to Navagero as the ball game was the ball itself. European balls were typically made of leather and stuffed with wool or feathers. These were something different. They “bounded copiously”, Navagero said, ricocheting in a headlong way unlike anything he had seen before. “I do not understand how these heavy balls are so elastic”. Navagero, d’Anghiera and Oviedo had a right to be confounded: they were encountering a novel form of matter. The balls were made of rubber. In chemical terms, rubber is an elastomer, so named because many elastomers can stretch and bounce. No Europeans had ever seen one before.

Rubber Fever

The first simple laboratory experiments, in 1805, gave little hint that rubber might be useful – although the scientist, John Gough, did discover the fact, key to later understanding, that rubber heats up when stretched. Only in the 1820’s did rubber take off, with the invention of the rubber galoshes. ‘Take off’ for Europeans and Americans, that is; South American Indians had been using rubber for centuries. They milked rubber trees by slushing thin, V-shaped cuts on the trunk, latex dripped from the point of the V into a cup, usually a hollowed-out gourd, mounted on the bark. In a process reminiscent of making taffy, Indians extracted rubber from the latex by slowly boiling and stretching out over than intensely smoky fire of palm nuts. When the rubber was ready, they worked into stiff pipes, dishes, and other implements.

Native people also waterproofed their hats and cloaks by impregnating the cloth with rubber. European colonists in Amazonia were manufacturing rubberized garments by the late eighteenth century, including boots made by dripping foot-shaped moulds into bubbling pots of latex. A few pairs of boots made their way to the United States. Cities like Boston, Philadelphia and Washington D.C. were built on swamps; their streets were thick with mud and had no sidewalks. Rubber boots there were a big hit.

The Epicentre of what became known as “rubber fever” was Salem, Massachusetts, north of Boston. In 1825, a young Salem entrepreneur imported five hundred pairs of rubber shoes from Brazil. Ten years later, the number of imported shoes had grown to more than 400,000, about one for every forty Americans. Villagers in tiny hamlets at the mouth of the Amazon moulded thousands of shoes to the dictates of Boston merchants. Garments impregnated with rubber were modern, high-tech, exciting- a perfect urban accessory. People flocked to stores.

The crash was inevitable. The idea of impermeable rubber boots and clothes was more exciting than the fact. Rubber simply didn’t work well. In cold weather, the shoes became brittle; in hot weather, they melted. Boots placed in closets at the end of the winter turned into black puddles by fall. The results smelled so bad that people found themselves burying their footgear in the garden. Public opinion swung violently against rubber.

Vulcanisation

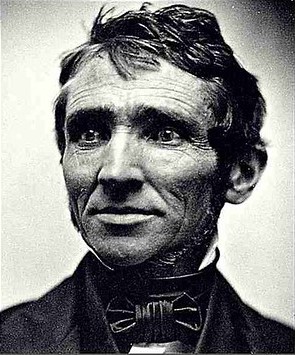

Charles Goodyear photographed by Southworth and Hawes

Just before the collapse, in 1833, a bankrupt businessman named Charles Goodyear became interested in –and obsessed by – rubber. It was typical of Goodyear’s entrepreneurial acumen that he began to seek financial backing for a rubber venture just at the time investors were planning their exits from the field.

A few weeks after Goodyear announced his intent to produce temperature stable rubber he was thrown into debtor’s prison. In his cell he began work, mashing bits of rubber with rolling a pin. He was untroubled by any knowledge of chemistry but boundlessly determined. All the while he was mixing toxic chemicals, more or less randomly, in the hope that they would make rubber more stable. Goodyear began mixing rubber with sulphur. Nothing happened, he said later, until he accidentally dropped a lump of sulphur-treated rubber onto a wood stove. To his amazement, the rubber didn’t melt.

By a circuitous path two thin, inch-and-a-half-long strips of Goodyear’s processed rubber ended up in the autumn of 1842 at the laboratory of Thomas Hancock, a Manchester engineer who had developed processes for manipulating rubber. Hancock was more organized and knowledgeable than Goodyear and had better equipment. For a year and a half he systematically performed hundreds of small experiments. Eventually he, too, learned that immersing rubber in melted sulphur would transform it into something that would stay stretchy in cold weather and solid in hot weather. Later he called the process “vulcanization”, after the Roman god of fire, Vulcan.

The British government granted Hancock a patent on May 21, 1844. Three weeks later, the U.S. government awarded Goodyear his vulcanization patent. Goodyear didn’t understand the recipe of vulcanization, but he did understand that at least he had a business opportunity. Showing a previously unsuspected knack for publicity stunts, he spent $ 30,000 he did not have to create an entire room made of rubber for the Great Exhibition of 1851 at the Crystal Palace in London, the first world’s fair. Four years later he borrowed $ 50,000 more to display an even more lavish rubber room at the second world’s fair, the Exposition Universelle in Paris. Parisians lost their urban hauteur and gawped like rubes at Goodyear’s rubber vanity table. Except for the unpleasant smell, Goodyear’s exhibit was a triumph. “Napoleon III invested him with the Legion of Honour” wrote the diplomat and historian Austin Coates, “and a Paris court sent him to prison for debt”. He received the medal in his cell. Goodyear was forced to sell some of his wife’s possessions to pay for their trip home.

Goodyear died four years later, still awash in debt. Afterward, Americans lionized him as a visionary. Books extolled him to children as an exemplar of the can-do spirit; a major tire company named itself after him. Meanwhile, Coates, noted, “Hancock received English treatment: due respect while living, fading notice when dead, and on some suitable centenary thereafter, a postage stamp”.

Neither Goodyear nor Hancock had any idea why sulphur stabilized rubber – or why, for that matter, unadulterated rubber bounced and stretched. Nineteenth-century scientists found bouncing balls exactly as mystifying as sixteenth-century Spaniards.

The last half of the nineteenth century was a heady time for chemistry. Immersing rubber in sulphur causes a chemical reaction in which rubber molecules link themselves together with chemical “bridges” formed of sulphur atoms. So ubiquitous are the bonds that a rubber band – a loop of vulcanized rubber – is actually a single, enormous, cross-linked molecule. With the molecules anchored together, they are more resistant to change: harder to align, harder to entangle, more resistant to extremes of temperature. Rubber suddenly becomes a stable material.

The impact of vulcanization was profound, the inflatable rubber tire-key to the adoption of both the bicycle and the automobile – being the most celebrated example. But rubber also made electrification possible: try to imagine a modern building without insulation on its wiring. Or imagine dishwashers, washing machines and clothes dryers without the belts that transmit the motion of their engines to the appliance itself. Equally important but less visible, every internal combustion engine contains many pipes and valves that channel, usually under pressure, water, oil, gasoline, and exhaust vapour. Unless the parts are manufactured perfectly, engine vibrations will cause liquids or gases to vent dangerously from joints. Flexible rubber gaskets, washers, and O-rings almost invisibly fill the gaps. Without them, every home furnace would be at constant risk of leaking natural gas, heating oil, or coal exhaust – a potential death trap.

In short three fundamental materials were required for the Industrial Revolution: steel, fossil fuels, and rubber.

The Rubber Rush

As this point, the primary source of natural rubber was latex from Hevea Brasilensis, native to the Amazon basin, the tree is most abundant on the borderlands between Brazil and Bolivia. The nearest ports to this area are those on the Pacific coast, across the Andes. Sending rubber to those ports would mean carrying it across the high, icy mountains. After doing that, shipping the latex to England would involve dispatching ships around the stormy southern tip of South America, a long and dangerous trip of almost twelve thousand miles. The entire route was so difficult, in fact, that the secretary of the Royal Geographical Society calculated in 1871 that it would be four times faster to ship rubber to London from the western amazon by transporting it down the Madeira River to the Amazon itself, and thence to the Atlantic.

Even in a time of crazy boom-and-bust cycles the rubber boom stood out. Brazil’s rubber exports grew more than tenfold between 1856 and 1896. Ordinarily such an enormous increase in supply would drive down prices. But instead they kept climbing. Attracted by tales of fortunes gained, speculators leaped into the market. New York rubber oscillated between $1.34 and $3.06 a pound. On top of that, the inflation, financial panics and political instability of the era caused the currencies of Brazil, Britain and the United States to gyrate wildly in value.

Still, rubber kept going up. Its “soaring price is turning rubber manufacturers gray”, the Times claimed on Mach 20, 1910. “Once ounce of rubber washed and prepared for manufacture is worth nearly its weight in pure silver”. The newspaper was hyperventilating, but not entirely wrong. One economist recently calculated that the average London price of rubber roughly tripled between 1870 and 1910.

Theatro de Paz, Belem

The financial centre of the trade was Belém. Founded in 1616 at the entrance to the world’s greatest river, it had a strategic location. The rubber boom allowed it to become, at last, what Amazonian dreamers had long hoped: the economic capital of a vibrantly growing realm. Convinced they were building the Paris of the Americas, Belem’s newly rich rubber elite filled the cobbled streets with sidewalk cafes, European style strolling parks and Beaux –Arts mansions. Social life centered around the neoclassical Theatro de Paz, where barons in box seats smoked cigars and drank cachaça, the distilled sugarcane liquor that is Brazil’s preferred high-alcohol beverage.

After inspection, the rubber went into series of immense warehouses that lined the shore like sleeping beasts. Rubber was everywhere, one visitor wrote in 1911, “on the sidewalks, in the streets, on trucks, in the great storehouses and in the air – that is, the smell of it”. Indeed, the city’s rubber district had such a powerful aroma that people claimed they could tell what part of the city they were in by the intensity of the odour.

Belém was the bank and the insurance house of the rubber trade, but the centre of rubber collection was the city of Manaus. Located almost a thousand miles inland, where two big rivers join to form the Amazon proper, it was one of the most remote urban places on earth.

Atop one hill was the cathedral, a Jesuit built structure with a design so austere that it looked like a rebuke to the monstrosity that dominated the next hill over. The Teatro Amazonas was a preposterous fantasia of Carrara marble, Venetian chandeliers, Strasbourg tiles, Parisian mirrors and Glasgow ironwork. Finished in 1897 and intended as an opera house, it was a financial folly: the auditorium had only 658 seats, not enough to offset the cost of importing musicians, let alone the alone the expense of construction.

Teatro Amazonas

Wide stone sidewalks with undulating black-and-white pattern led downhill from the theatre through a jumble of brothels, rubber warehouses and nouveau-riche mansions to the docks: two enormous platforms that rode up and down with the river on hundreds of wooden pillars. State governor Eduardo Ribeiro aggressively boosted the city, laying out streets in modern grid, paving them with cobblestones from Portugal (the Amazon had little stone), overseeing the installation of what was then one of the globe’s most advanced streetcar networks (fifteen miles of track), and directing the construction of three hospitals (one for the Europeans, one for the insane, one for everybody else).

A celebrant of urban life, Ribeiro took part in everything his city had to offer, including its sybaritic whorehouses, in one of which he died amid what historian John Hemming delicately referred to as “a sexual romp”. The city’s many brothels were largely for the rubber tappers and field operatives who staggered into Manaus after months of labour on remote tributaries. The owners and managers had mistresses, with whom they sported in the decadent style then fashionable.

In the 1890s the boom went still further upstream, into the Andean foothills – areas that until then had been regarded as useless, and so left largely to their original inhabitants, most of whom had minimal contact with Europeans. Because H.brasilensis can’t tolerate the cooler temperature on the slopes, entrepreneurs focused on another species, Castilla elastic, which provided a less-valuable grade of rubber known as caucho. “Caucheiros”, rather than futilely protect the trees, simply cut them down, gouged off the bark, and let the latex drain into holes dug beneath the fallen trunk. Sometimes collectors could obtain several hundred pounds of the latex from a single tree, thus making up in volume for caucho’s lower price.

Because caucheiros killed the tree they harvested, they naturally put a premium on being the first into a new area. The goal was to extract the most rubber in the least amount of time; every minute not at the axe was a minute when someone else was taking down irreplaceable trees. Work crews spent weeks or months trekking from tree to tree through steep, muddy, forested hills, carrying heavy loads of caucho from the areas they had just looted. Few people from outside the area were willing to come into the forest for this. Caucheiros thus turned to the people who already lived there: Indians. The situation invited abuse – and there are always people ready to take up such invitations. Among them was Carlos Fitzcarrald, son of an immigrant to Peru who had changed his name from the hard-to-pronounce “Fitzgerald”. Beginning in late 1880s Fitzgerald forced thousands of Indians to work the caucho circuit.

More brutal was Julio Cesar Arana. The son of a Peruvian hat maker, Arana came to exert near-total command over more than twenty-two thousand square miles on the upper Putumayo River, then claimed by both Peru and Colombia.

Not wanting to lure labourers from other areas with high wages, he turned to indigenous people. At first they were willing to do some rubber collecting in exchange of knives, hatchets, and other trade goods. But when Arana asked for more they balked. So he enslaved them. By 1902 he had five Indian nations under his thumb. Caucho flowed from his land in ever-larger amounts. He controlled his slave force with a goon squad led by more than an hundred toughs imported from Barbados. Nobody other than Arana’s agents was allowed to enter Putumayo from outside. Twenty-three custom-built cruise boats enforced his rule. Arana had incorporated his company in London in an attempt to go public and cash out, as software entrepreneurs would do a century later.

The slavery was therefore a British matter. Eventually there was a parliamentary investigation and a yearlong public furore. London sent an investigatory team that included Roger Casement, an Irish–born British diplomat who was a pioneering human rights activist (he had exposed atrocities committed in the Congo by agents of Belgium king Leopold II). Casement shuttled about the Putumayo, confirming Hardenburg’s charges by obtaining detailed confessions of murder and torture. In a misguided fit of nationalism, Peru defended its citizen against foreign meddling. Nonetheless Arana’s empire disintegrated. He died penniless in 1952.

Wickham changes the game for Britain

If this ecological tumult could be laid at the door of a single person, it would be Henry Alexander Wickham. Wickham’s life is difficult to assess: he had been called a thief and a patriot, a major figure in industrial history and hapless dolt whose main accomplishment was failing in business ventures on three continents. He was born in 1846 to a respectable London solicitor and a milliner’s daughter from Wales. When the boy was four, Cholera took his father’s life and the family he left behind slid slowly down the social ladder. Nonetheless at the end of his days he was a respected man. Crowds applauded as he walked onto testimonial stages wearing a silver-buttoned coat and a nautilus-shell tie clip. He was knighted at the age of seventy-four.

Wickham won the honour for smuggling seventy thousand rubber tree seeds to England in 1876.

As a young man, Sir Clements Markham had directed a British quest in the Andes for cinchona trees. Cinchona bark was the sole source of quinine, the only effective antimalarial drug then known. Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador, which had a monopoly, zealously guarded the supply, forbidding foreigners to take cinchona trees. Markham dispatched three near-simultaneous covert missions to the Andes, leading one himself. Hiding from the police, almost without food, he descended the mountains on foot with thousands of seedling in special cases. All three of these teams obtained cinchona which was soon thriving in India. Markham’s project saved thousands of lives, not least because Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia were running out of cinchona trees – they had killed them by stripping the bark. Riding the success to the position of director of the India Office’s Geographical Department, Markham decided to repeat the feat with rubber trees. British industry’s dependence on rubber was leaving the nation’s prosperity in the hands of foreigners, he believed.

Markham argued, “It’s hardly possible to over-rate the importance of securing a permanent supply”. Glory would attach to those who secured that supply. In the early 1870’s, Markham let it be known that Britain would pay for rubber seeds. When the seeds arrived, they would be sown at the Royal Botanic Gardens, at Kew in Southwest London, and the successful seedlings dispatched to Britain’s Asian colonies. Two separate hopeful adventurers sent batches of rubber seed. Neither batch would sprout. Wickham became the third to try. Wickham gathered seventy thousand seeds, enough to pay for passage back to Britain. Today Wickham is reviled in Brazil. Tourist guides refer to him as the “prince of thieves”, a pioneer of what has become to be called “bio-piracy”.

Two months after Wickham appeared in London, Kew shipped out the seedlings, most of them to British Ceylon, known today as Sri Lanka.

Henry Ridley and the rise of the Malaya Rubber

Rubber trees in Malaysia, Yun Huang Yong, Flickr Creative Commons

At the same time that the seedlings were dispatched to Sri Lanka, a further two cases, containing fifty seedlings, were sent to Singapore. There, the Singapore Botanical Garden’s new director, Henry Ridley, set to work on rubber plants, comparing them with other rubber-producing plants, and figuring out the best way to harvest latex without harming or killing the trees and coming up with a method that is still used to this day.

Ridley’s zealous persistence in persuading Malaya’s planters to grow rubber trees earned him less than flattering nicknames such as “Mad Ridley” and “Rubber Ridley”. During the 1890s and early 1900s, he devised successful propagation methods and advocated the large-scale cultivation of rubber in Malaya. Initially, planters largely ignored his advice until their coffee plantations were devastated by disease and they desperately required a new cash crop. During this time, demand for rubber soared as the automobile industry boomed. By 1912, Malaya was producing more rubber than Brazil, and when prices fell the Brazilian rubber industry was reduced to dust.

Fordlandia

The first real chance for Brazil to recover occurred in 1922, when British colonies in Asia, which had overplanted rubber, sought to control prices by forming a cartel. Among those enraged by this action were Harvey Firestone, the world biggest tire maker, and Henry Ford, the world biggest car maker.

Firestone responded by creating a huge rubber plantation in Liberia, West Africa. Ford planned one of equal size in the Amazon. Ford hired a Brazilian go-between who in 1927 sold him almost four thousand square miles of land up the Tapajos river that happened to be owned by the go-between. To house his workers Ford built a replica of a middle-class Michigan Town, complete with a hospital, schools, stores, movie theatres, Methodist churches and wooden bungalows on tree-lined streets. On a hill was the Amazon basin’s only eighteen-hole golf course. Orderly and straitlaced as Ford himself, the town was the opposite of boomtown Manaus. Wags immediately dubbed the project Fordlandia.

Water tower and main warehouse building in Fordlandia, Brazil. Amit Evron, Wikimedia Commons

For Ford, the next few years were a series of unhappy surprises; after the first season’s rubber trees died did the company find out that H. brasilensis must be established at particular times of the year to thrive. Only after paying steamship bills did the company realize that it would not be possible to offset the cost of clearing all the hardwood trees on its land by selling the timber in the United States. And only after planting thousands of acres did the company learn that the Amazon has fungus, Microcyclus ulei, that is partial to rubber trees. This last sentence is imprecise. The company did know that M. ulei existed. What it didn’t grasp was that there was no way to stop it. M. ulei causes South American leaf blight.

The disaster effectively ended Fordlandia, though it wasn’t formally abandoned until 1945. Its fate made the most Brazilians conclude that rubber plantations are not viable in the Amazon. When Ford bought land in Brazil, 92% of the world’s natural rubber came from Asia. Five years after Fordlandia ended the figure was 95%.

The Chinese move in

Natural rubber still claims more than 40% of the market, a figure that has been slowly rising. Only natural rubber can be steam-cleaned in a medical sterilizer, then thrust into a freezer-and still adhere flexibly to glass and steel. Big airplane and truck tires are almost entirely natural rubber; radial tires were entirely synthetic. High tech manufacturers and utilities use high-performance natural rubber hoses, gaskets and O-rings. So do condom manufacturers – one of Brazil’s few remaining natural-rubber enterprises is a condom factory in the western Amazon.

With its need for materials that can withstand battle conditions the military is a major consumer – which is why the United States imposed a rubber blockade on China during the Korean War.

The blockade helped convince the Chinese of the need to grow their own H. brasilensis. In the 1960s the People’s Liberation Army worked to turn the prefecture into a rubber haven. Xishuangbanna plantations were, in effect, army bases; entry was forbidden to outsiders. Outsiders included the Dai and Akha who lived nearby. As suspicious of minorities in the mountains as the Qing, the Communists imported more than 100,000 Han workers, many of them urban students from faraway provinces, and put them into labour gangs charged with revolutionary fervour. “China needs rubber” they were told. “This is your chance to use your hands to help your country”. Workers were awakened every day at 3:00 am and sent to clear the forest, one former Xishuangbanna labourer told anthropologist Judith Shapiro, author of Mao’s War Against Nature.

Even as burgeoning China became the world biggest rubber consumer, its rubber producers were running out of space in Xishuangbanna – every inch of land was already taken. They looked enviously over the border at Laos; with about six million people in an area the size of the United Kingdom, it is the emptiest country in Asia. But the real push didn’t begin until the end of the decade, when China announced its “Go-Out” strategy, which pushed Chinese companies to invest abroad. No one knows exactly how much H. brasilensis is now in Laos; the Laotian government estimated that rubber covered seven hundred square miles of the nation by 2010. And the pace of clearing will only accelerate, along with the effects of that clearing.

More than a century ago, a handful of rubber trees had come to Asia from their home in Brazil. Now the descendants of these trees carpet sections of the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and parts of southern China. Across the border H. brasilensis was marching into Laos and Vietnam. A plant that before 1492 had never existed outside the Amazon basin now dominates the Southeast Asian ecosystem.