CONQUISTADORS, WAR AND REVOLUTION

INTRODUCTION

Throughout its history Mexico has been convulsed by a series of epic, violent and bloody struggles that have defined the culture and identity of this complex nation.

This 4X 1 hour mini-series looks at this often overlooked history of America’s next door neighbour, a history that has both been influenced and involved the United States. Despite this, relatively little is known of the events that have shaped Mexico, and how those events are reflected in the character of the country today.

While the world maybe aware of the Spanish conquest led by Hernan Cortes and his fellow Conquistadors in the 16th century, and the devastating impact this conquest had on Mexico’s pre-Hispanic civilizations, an exploration of how events unfolded in the subsequent four hundred years until the Mexican revolution, has largely been ignored.

While the names of Cortes, Zapata, Villa, Santa Ana and Riviera are familiar, and the Battle of the Alamo identified as an iconic American historic event, the precise role played by these names and places and events, such as the American Mexican War, remain somewhat of a mystery to anyone outside Mexico.

This is a history of conquest with all its bloody and dramatic consequences; not just of battles and wars, but of feuds, shifting alliances, trickery, intrigue, executions, assassination and exile.

Episode One

The Spanish Conquest lays the ground for 300 years of colonial rule which made Spain the richest country in Europe and divided the country with a class system which still impacts today.

Episode Two

The War of Independence charts the violent struggle by Mexicans to break free, the subsequent loss of almost half of its territory to the US, and the resultant decades of instability that followed.

Episode Three

This episode explores the conflict between church and state which led to civil war and a French invasion which made an Austrian prince , Maximillian , Emperor of the so called Second Empire. He was defeated and executed by Benito Juarez one of Mexico’s great independence heroes who was succeeded by Porfirio Diaz, who would then rule Mexico for more than 30 years

Episode Four

Explores the Mexican Revolution in the early part of the last century, another hugely bloody event, but one which achieved the foundations of a modern Mexican state with myriad cultures we know today.

BRIEF

The Spanish Conquest

In 1517, the first Spaniards arrived in what is today known as Mexico and skirmished with the Maya off the Yucatan coast. Another Spanish expedition, under Herman Cortez, landed on Cozumel in February 1519. The coastal Maya were happy to tell Cortez about the gold and the riches of the Aztec empire in central Mexico.

Cortez arrived when the Aztec empire was at the height of its wealth and power. Moctezuma II ruled over the central and the southern highlands and extracted tribute from lowland peoples. His greatest temples were plated with gold and encrusted with the blood of sacrificial captives. A fool, a mystic and something of a coward. Moctezuma dithered in Tenochtitlan while Cortez blustered and negotiated his way into the highlands, cloaking his intentions. Moctezuma, terrified by the Spaniards military tactics and technology, was convinced that Cortez was the god Quetzalcoatl making his long-awaited return.

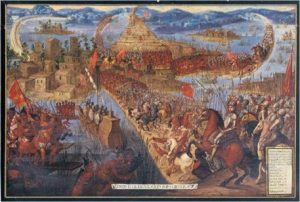

By the time he arrived in the Aztec capital, Cortez had accumulated 6000 indigenous allies who resented paying tribute to the Aztecs. In November 1519, he took Moctezuma hostage to try to leverage control of the empire.

Moctezuma was killed during the attack – whether by his own men or by the Spaniards is not clear. Cortez laid siege to Tenochtitlan, aided by rival Indians and a devastating smallpox epidemic. When the Aztec capital fell in 1521, all the central Mexico lay at the conqueror’s feet, vastly expanding the Spanish empire. The king hastened to legitimize Cortez’s victorious pirate expedition after the fact and ordered the forced conversion to Christianity of the new colony, to be called New Spain. By 1540, New Spain included possessions from Vancouver to Panama. In the 2 centuries that followed, Franciscan and Augustinian friars converted millions of Indians to Christianity, and Spanish lords build huge feudal estates without Indian farmers serving as serfs. Cortez’s booty of silver and gold made Spain the wealthiest country in Europe.

Cortez set about a new city upon the ruins of the Aztec capital, collecting in tributes, some of them in labour, that the Indians once paid to Moctezuma. This model for building the new colony backfired over the next century, as the workforce perished from diseases imported by the Spaniards.

Over the 3 centuries of colonial rule, 361 viceroys governed Mexico while Spain became the richest country for Europe from the New World gold and silver chiselled out the Indian labour. The Spanish elite build lavish home filled with ornate furniture and draped themselves in imported velvet, satins and jewels. Under the new class system, those born in Spain (peninsulares) were considered superiors to Spaniards born in Mexico (criollos). People of the other races and the casta (Spanish-Indian, Spanish-African or Indian-African mixes) occupied society’s bottom rungs.

Criollo resentment of Spanish rule simmered for years over taxes, royal monopolies, bureaucracy, peninsulares’ superiority, restrictions on commerce with Spanish and other countries, and the 1767 expulsion of the largely criollo Jesuit clergy. In 1808, Napoleon invaded Spain, deposed Charles IV, and crowned his brother Joseph Bonaparte. To many in Mexico, allegiance to France was unthinkable. The next logical step was revolt

The War of Independence

Prior to Independence , Mexico was part of New Spain with territory and missions throughout what is now California, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Texas and even part of Wyoming.

In 1810, Father Miguel Hidalgo set off the rebellion with his grito, the fabled cry for independence, from his church in the town of Dolores, Guanajuato. With Ignacio Allende and a citizen army, Hidalgo marched toward Mexico City. Although he ultimately failed and was executed, Hidalgo is honoured as the “Father of the Mexican Independence”. Another priest, Jose Maria Morelos, kept the revolt alive with several successful campaigns before he, too, was captured and executed in the 1815.

When the Spanish king who replaced Joseph Bonaparte decided to institute social reform in the colonies, Mexico’s conservative powers concluded they didn’t need Spain after all. Royalist Augustin de Iturbide defected in 1821 and conspired with the rebels to declare independence from Spain, with himself as emperor. However, internal dissension quickly deposed Iturbide, and Mexico was instead proclaimed republic.

The young, politically unstable nation ran through 36 presidents in 22 years, during which it lost almost half of its territory in the disastrous Mexican-American war (1846-48). During the War, American troops, led by soldiers such as Grant who would later become Civil War heroes, occupied Mexico City. The US took 15 million dollars off. Mexican debt for what was the third biggest land acquisition in its history after the Louisiana Purchase and the purchase of Alaska.

The central Mexican figure during this time, Antonio López de Santa Anna, who would command the Mexican forces at The Alamo, was flexible enough in those volatile days to portrait himself variously as a liberal, a conservative, a federalist and a centralist. He assumed the presidency no fewer than 11 times and just might hold the record for frequency of exile. He was ousted for good in 1855 and finished his days in Venezuela.

Amid continuing political turmoil, conservative force, with some encouragement from Napoleon III, resolved to bring in a Hasburg to regain control. With French backing, Archduke Maximilian of Austria stepped in as emperor, but ragtag Mexican troops defeated the well-equipped French in a battle near Puebla in 1862 (now celebrated as Cinco de Mayo). A more successful second attempt seated Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph as emperor. Maximilian developed a genuine fondness in the Mexican people and upheld such polices as land reforms, religious freedom and extending the right to vote beyond the landholding class. But he never overcame the opposition of Mexican extremists or refusal of many foreign countries, including the United States, to recognise his government. After 3 years of civil war, the French abandoned the emperor, leaving Maximilian to be captured and executed in 1867.

Maximilian’s adversary and successor (as president of Mexico) was Benito Juarez, a Zapotec Indian lawyer and one of Mexico’s greatest heroes. Juarez plans and visions bore fruit for decades.

The Mexican Revolution

A few years after Juarez’s death, one of his generals, Porfirio Diaz, seized power in a coup. He ruled for 24 years from 1877 to 1911, a period now called the Porfiriato. He maintained his rule through repression and by courting the favour of powerful nations. Generous in his dealings with foreign investors, Diaz became the archetypal entreguista (one who sells out his country for private gain). With foreign investment came the concentration of great wealth in a few hands and social conditions worsened.

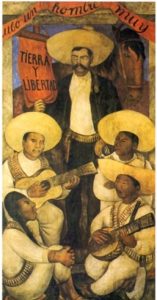

In 1910, Francisco Madero led an armed rebellion that became the Mexican Revolution (“La Revolucion” in Mexico; the revolution against Spain is the “Guerra de Independencia”). Diaz was exiled and is buried in Paris. Madero became president, but Victoriano Huerta, in collusion with U.S. ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, betrayed and executed him in 1913. Those who had answered Madero’s call rose up again – in support of the great peasant hero Emiliano Zapata in the south and the seemingly invincible Pancho Villa in the central north, flan by Alvaro Obregon and Venustiano Carranza. They eventually expelled Huerta and began hashing out a new constitution. Villa was assassinated in 1923.

For few years, Carranza, Obregon and Villa fought among themselves; Zapata did not seek national power, though he fought tenaciously for land for the peasants. Carranza, who was president at the time, betrayed and assassinated Zapata. Obregon finally consolidated power and probably had Carranza assassinated. He, in turn, was assassinated when he tried to break one of the tenets of the revolution – no re-election. His successor, Plutarco Elias Calles, learned this lesson well, installing one puppet president after another, until Lazaro Cardenas, elected in 1934, exiled him. At last, the Revolution appeared to have a chance. Cardenas implemented massive land redistribution, nationalized the oil industry, instituted many other reforms and gave shape to the ruling political party, which evolved into today’s Partido Revolucionario Institucional, or PRI. Cardenas is practically canonized by most Mexicans.