The French Revolution

The French Revolution is one of the most important instances of political upheaval in history, marking France’s transition from Empire to Republic after centuries of monarchy. Lasting a period of ten years, the French Revolution was a time of violence and major change, which not only changed France profoundly but also reshaped the entire world, suggesting the vulnerability of monarchies and paving the way for republics as a common means of ruling.

What Caused The Revolution?

The French Revolution was borne out of a diverse range of causes, some long-term factors, others more short-term catalysts. These causes covered a wide range of themes, including economic, political and social ones.

Social

If there were to be a chief instigator behind the eruption of the French Revolution, it would arguably be the rampant social inequality within France. The country was plagued by extreme poverty, which was exacerbated by a cruel and antiquated feudal system. The peasantry, the vast majority of whom worked in agriculture, were forced into paying taxes to the nobility and to the clergy. This ensured they would be unable to support and often feed their families. Despite far outnumbering the clergy and the nobility, the peasantry did not own near as much land.

By contrast, the nobility owed no taxes to the state at all despite their far superior wealth. The clergy, itself mainly comprised of members of the bourgeoisie and the nobility, was similarly exempt from these punitive measures. The growing power of the nobility and its seeming immunity to taxation, especially in such trying times, lead to a rapid intensification of class resentment, which played a significant role in the French Revolution

Cultural

An additional long-term cause was the sense of cultural change unravelling around Europe. The French Revolution fell into the broader period known as ‘The Age of Enlightenment’, which had promoted ideas such as equality and individualism, which directly challenged the institutions of the Catholic Church and the French Monarchy. The archaic ideas represented by these institutions were steeped in tradition and the ideas espoused during the Enlightenment resonated with a disenfranchised population. The successful implementation of these ideas in America created a blueprint for apparent success, which gave further impetus to the French.

Economic

Closely tied with the social factors were the economic distress across France during the Revolutionary period. The taxation of the peasantry had increased to an enormous extent due to the state’s high debt levels. This was due to the French support of the American Revolution, which had left the state’s economy in a fragile and near-bankrupt position. The monarchy’s inability to deal with this vast debt played a major role in fuelling resentment towards it. The peasantry, already burdened by heavy taxation, were pushed to the very brink by these new measures, which could be viewed as a means of supporting the lavish lifestyles of the upper echelons of society. The exemption of the nobility and the church from taxation not only complicated the economic situation but intensified resentment.

Political

A major factor behind the collapse of the monarchy were its inherent political flaws and its failures to adapt to the rapidly changing landscape. Despite the continuation of the inhumane and ineffective taxation system, there had long been a recognition amongst certain ministers at revising it. There were propositions in taxing the nobility in addition to the peasantry, which was met with hostile resistance amongst the aristocracy, undermining a critical area of support for the monarchy. It was opted to deregulate the grain market, which had disastrous effects. This drove the price of bread up massively during period of poor harvest and triggered the Flour War, a period of political unrest in 1775, which is viewed by many as a catalysing event in the French Revolution. The indecisiveness of Louis XIV and his court proved particularly costly, and undermined bases of political support and leaving him vulnerable to the looming revolution.

Life At Versailles

A major reason for the seething and fast-rising resentment towards the French monarchy was the sheer excess and opulence of the royal court and the aristocracy. This excess was exemplified by the lifestyles of King Louis XIV and his wife Marie Antoinette. The Royal Court was renowned for lavish parties, excessive feasts and unbridled hedonism. This was in stark contrast to the rampant poverty and hunger of the peasantry. The ignorance of the Royal Court to grasp the severity of this problem played a significant role in their downfall.

Louis The XVI

The final King of France, Louis XVI is a more complicated figure than he initially appears. Often villainised as the epitome of upper class excess and tyranny, he was far more intelligent than he is often portrayed. The early parts of his reign were marked by a genuine effort at reform as he clearly understood the fast-rising hostilities. Despite these positive attributes, Louis XVI clearly played a role in his own undoing. His indecisiveness rendered him unable to fully grasp the severity of public outrage while a number of misguided policies he implemented only intensified resentment towards him. His excessive lifestyle also did him no favours, and fed into the image of a tyrannical exploiter of the masses.

Marie Antoinette

Louis XVI’s wife, best known for her misguided, enduring words: ‘Let them eat cake’, epitomised the class conflict as much as her husband. A member of Austrian Royalty, she married Louis XVI at a young age, she was an initially popular figure. Her fall from grace arguably even more staggering than that of her husband. Marie Antoinette, according to her detractors, encapsulated the ignorance, excess and hedonism associated with the royal family and the upper class, criticisms that are at least partially valid. Her ignorance to the plight of the peasantry, opposition to political reform and lavish lifestyle made her a clear enemy to those seeking change.

Storming Of The Bastille

Arguably the most pivotal moment of the French Revolution was the Storming of the Bastille, commemorated in modern times by the holiday Bastille Day. Taking place on 14 July 1789, this saw tensions escalate from an uprising into a full-fledged revolution. The Bastille was a major prison in Paris, which symbolised the idea of Royalist tyranny. At the time, there were only seven prisoners held captive in the Bastille, however the storming was a far more symbolic victory than a tangible one. It represented the seizure of one of the most oppressive sites in the country-a symbol of the royal abuse of power. The incident had significant reverberations across the country, triggering the ‘Great Fear’, a period of mass panic throughout the country, which saw tensions escalate into a full-scale revolution.

Arrest Of The Monarchs

In the aftermath of the Bastille, Louis XVI saw his grip on power weakened significantly. The leader’s power had transferred from that of an absolute monarch to a constitutional monarch, meaning power was more equally weighted between himself and parliamentary officials. Louis XVI remained an indecisive and unpopular figure during this final period of his rule. The death of Honore Gabriel Riqueti, the Count of Mirabeau, a major figure in the Revolution and a mediator between the Crown and the politicians, further compromised Louis XVI’s standing. He found his powers increasingly hamstrung by a more powerful government and grew increasingly detached from their modernising attitudes.

By 1791, a mere two years later, Louis XVI and his family attempted to flee from their predicament and trigger a counter-revolution, but these plans were quashed as they were arrested in the town of Varennes. This proved to be a major turning point in the Revolution and significantly intensified public animosity towards the monarchy and effectively sealed their fate.

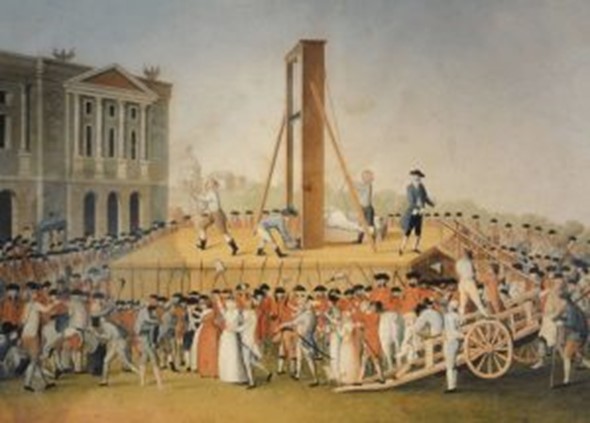

The Guillotine

One of the most potent symbols of the French Revolution was the guillotine, a method of execution which left its victims decapitated. This was the means by which many enemies of the Revolution met their fates, including the King and Queen Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. The Guillotine has polarised people as a symbol during the Revolutionary Period, with some viewing it in a celebratory light due to its role in overthrowing the monarchy while others view it in a more objectionable light due to its association during the Terror which followed.

The Execution Of The Monarchs

Following their arrest, the monarchs were imprisoned in the Tour de Temple, an old Medieval fortress in Paris. While they were imprisoned, the National Assembly declared the abolition of the monarchy whilst establishing France as a Republic. Charged with treason for his attempts at subverting the First French Republic, Louis XVI was sentenced to death by the Convention, who voted in overwhelming favour of his execution due to the wealth of evidence against him. Louis XVI was executed in January 1793, with records showing he went to his death in a dignified manner. His widow Marie Antoinette was imprisoned for several months thereafter before meeting her own execution in October. With the monarchy extinguished, a new Republic loomed ahead. Despite this, the conflict was far from over.

The Terror

With the monarchy vanquished and the First French Republic promptly established in its place, the transition into peaceful democracy was complicated by continued tensions between a number of warring factions. Civil war was escalating while external armies were closing in on a country gripped by chaos. The government, facing enemies on all fronts, decided to impose Terror to maintain their grip on power in increasingly fraught times. Those they deemed enemies to the Revolution were arrested and executed en masse. Under the leadership of the notorious Maximilien de Robespierre, the Committee of Public Safety assumed a virtually dictatorial position, vanquishing enemies from a variety of different positions to their own. During this period it is estimated that 17,000 people were executed while over 300,000 were arrested.

What Happened Next?

The period known as the ‘Great Terror’ was brought to an end with the event known as the Thermidorian Reaction on 27 July 1794, which saw the downfall of Robespierre and his extremist underlings. Robespierre and several others were arrested and executed. Filling in the power vacuum was a council otherwise known as the Directory, who could not quell the ongoing instability, causing further economic distress and continuing on costly military efforts abroad. The Directory’s mismanagement caused in its own downfall in 1799 when a coup led by Napoleon Bonaparte was successfully carried out. Napoleon’s coup is generally considered to be the end of the French Revolution, ushering in a new period of French history dominated by military incursions abroad. Regardless, the French Revolution remains the definitive turning point in the country’s history, its effects continuing to resonate within the country and far outside its borders.