The Lost World Of Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, naturalist, explorer, collector, patron and President of the Royal Society for more than 40 years was one of Australia’s founding fathers. As a young botanist, he accompanied Captain Cook on his circumnavigation and voyage of discovery to The South Seas, and yet a true picture of Banks’s life has never emerged.

Early Life

Joseph Banks was born in London in 1743. His youth was spent on “Revesby,” the Banks’ family estate in Lincolnshire, England. Banks inherited the estate from his father, who died when Banks was 16 years old. Banks was to oversee the management of the 10,000-acre estate for the rest of his life.

Eton, Oxford & Cambridge

Banks was sent to the traditional finishing schools of the aristocracy and the English upper class. Bored with lessons at Oxford, Banks hired a tutor from Cambridge to assist in his self-taught study of Botany. At the end of his life, he bestowed some of his massive collection to Christ Church, his Oxford College.

The Swedish Connection: Linnaeus, His Apostles & Daniel Solander

Banks’ life and achievements are closely linked to the work and discoveries of Swedish Botanist, Carl Linnaeus.

Linnaeus was responsible for a plant naming system still in use today, a vastly devastating impact that has only recently begun to be seriously critiqued by scholars and thinker around the world. He worked as a Professor in the Medical Department of Uppsala University, and it was initially for medical purposes that Linnaeus cultivated his garden there. Even today, the garden is laid out to the same specifications.

Linnaeus’ disciples or apostles, as his followers were known then, were dispatched around the world to collect plants. Linnaeus’ favourite disciple was Daniel Solander, whom Linnaeus had sent to England to learn more about English horticultural methods.

Solander met Banks at the British Museum, where Solander was curating the works of Sir Hans Sloane: the Chelsea Physic Gardens and a massive collection of plants, which Sloane had left to the Nation when he died in 1739.

The sociable and well-liked Solander never returned to his native Sweden, much to the disappointment of Linnaeus.

The ‘Endeavour’ Journey

Banks paid an equivalent of ten million dollars to secure passage with his entourage on “Endeavour,” a ship commanded by Captain James Cook. Banks’ team included Solander, artists, Sydney Parkinson and James Buchan – a draftsman, James Sporing, plus three servants and his two greyhound dogs.

The Journey Begins

The object of the voyage was to track the “Transit of Venus” in Tahiti, and thereafter, to head further west to explore and chart what was thought to be a great southern land.

However, only Banks, Solander, and one of the servants survived the journey, which lasted more than three years.

Death In Chile

After crossing the Atlantic, Banks and Solander went botanizing, when the boat anchored in Rio de Janeiro. Thereafter, they headed south to Cape Horn and at Tierra del Fuego, they landed at a site that Cook named the “Cape of Good Success.”

But when caught in a freak snowstorm, the expedition proved to be disastrous, taking the lives of Banks’ two servants.

Soon thereafter, Banks’ draftsman, Robert Buchan had an epileptic fit and died at sea. No other deaths among the crew were recorded for more than a year until the “Endeavour” landed on the shores of the East coast of Australia.

Tahiti

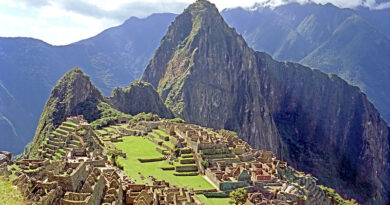

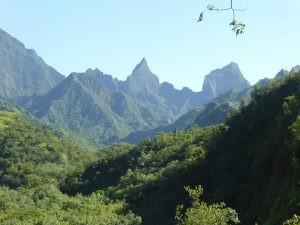

Tahitian Landscape

Banks and Solander noted more than a hundred new plant species native to Tahiti, including the Gardenia, the national flower of Tahiti, and the Breadfruit Tree, which was to obsess Banks for the next thirty years, culminating in the ill-fated Bounty expedition.

Banks’ botanic artist, Sydney Parkinson, sketched some of the first images of the natives and their way of life, another job that he inherited after the death of Banks’ artist, James Buchan.

Cook relied on Banks as the mediator with the natives. Banks led the trading efforts, bartering the “Endeavour’s” collection of iron nails and axes in exchange for much-needed supplies, such as coconuts and hogs.

Many of the crew, including the adventurous Banks, had sexual relations with the Tahitians, a fact that troubled Cook.

On leaving Tahiti, after a stay of three months, Banks persuaded Cook to bring onboard a Tahitian Chief and skilled navigator, Tupai, who was instrumental in guiding the “Endeavour” on its westward journey across the Pacific.

New Zealand

New Zealand was one of the last lands to be colonized. The Polynesian Maori arrived there after migrating across the Pacific in the 15th century. There they hunted to extinction the giant flightless bird known as the Moa, a Jurassic creature only found on the island.

Banks and Solander collected more than three hundred plant species, including many unique, giant tree ferns, and the flax plant, another species that obsessed Banks, given its suitability for rope making and sailing cloth.

Unlike the Tahitians, the fierce and warlike Maori provided an intimidating welcome to the Europeans. Despite the presence of Tupai, who understood the Maori language, there were frequent misunderstandings between the crew and the Haka, who interpreted them as invaders and therefore, a threat. On the first landfall at the site of modern-day Gisborne, on the east coast of the North Island, several Maori were shot and killed by Cook and his crew. Cook later renamed the site, “Poverty Bay.”

Cook spent six months circumnavigating the islands and producing a map that is still used today. Intrigued by the customs and cannibalism of the Maori as noted in his diary, Banks collected samples of the Maoris’ weapons and their intricate woodcarvings.

Australia

Australian Wattle

The “Endeavour” made landfall on the eastern coast of Australia on April 28th, 1770, at a place Cook named Botany Bay, located just a few miles south of modern-day Sydney.

Banks and Solander’s plant hunting on the undiscovered eastern seaboard of Australia produced the most significant part of their collection gathered during the three-year expedition.

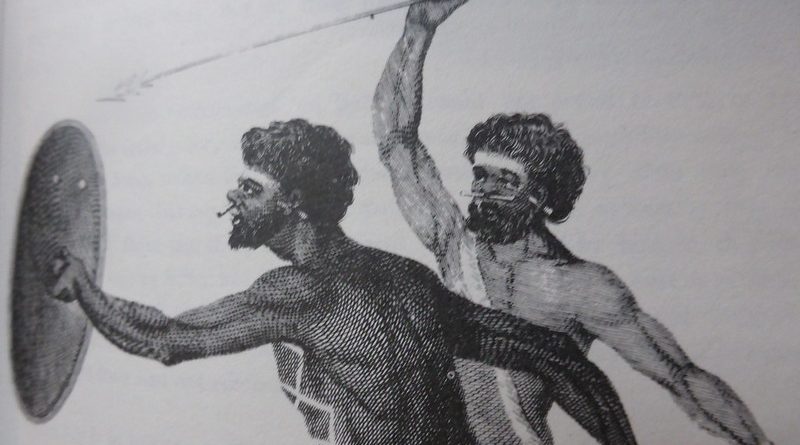

Less successful, however, were their encounters with the indigenous Aborigines, who were either disinterested or hostile to the visitors for whom they regarded as invaders.

On April 28, at Botany Bay, musket shots were fired at first contact, in order to deter the Aborigines. Spears and shields were seized. One of the Aborigines’ shields, now an artefact, is held today by the British Museum and regarded as one of the most important objects of its collection.

The “Endeavour” and its crew sailed northwards following and charting the coast until the ship ran aground, near modern-day Cooktown on the Queensland coast. The six-week layover for repairs at a place later renamed after ship, the Endeavour River, provided Banks and Solander with their best opportunity for plant hunting expeditions. Many of the most valuable samples from the journey came from there. Parkinson sketched the kangaroo, the first known western image of the creature, and also documented further exchanges with the Aborigines.

The Journey Home

After repairs to the ”Endeavour” were completed, Cook set course northwards through the East Indies on the long journey home. But in Batavia, disaster struck. More than a third of the crew died. Banks’ artist, Parkinson, Tupai, and the astronomer, Green, all lost their lives as disease swept through the crew in a matter of weeks.

Celebrity

When the “Endeavour” finally made it home three years after it left, it was big news. The journey made Banks famous, as he was soon being courted and celebrated in London society.

Banks’ circle of influence included famous names in London, during the 1770s and the following decade, such as Boswell and Johnson, an artist, Sir Joshua Reynolds, who, along with Samuel West, painted his portrait. Banks became a member of several societies, including the intriguingly named “Dilettante Society,” as was custom at the time for rich aristocrats, enjoying the Grand Tour. Banks was lampooned in the press, and caricatured as “The Botanic Macaroni,” and the “Great South Sea Caterpillar.”

Banks set up residence at 32 Soho Square in the heart of London. For the next thirty years, he played host to explorers, naturalists and botanists, who came to marvel at his collection, which he willingly shared. Solander moved in, combining the role of the colleague and personal secretary, until his untimely and early death of a stroke in 1783. Solander’s death devastated Banks; it is often thought that it was the reason for his massive pictorial record of the “Endeavour” journey, known as the “Florilegium,” which was never finished.

Banks: Patron Of Artists

Banks patronage of artists before, during, and after his epic journey of discovery was a common thread in his career. In an age before photography, artists were critical of visualizing far away places. Yet Banks searched out the best artists to join his many missions, organizing them for more than fifty years.

Sydney Parkinson was the most famous and prolific of Banks’ artists, on account of his magnificent work onboard the “Endeavour.” Banks also promoted the Austrian artist, Ferdinand Bauer, who accompanied Matthew Flinders on his famous circumnavigation of Australia, along with William Westall. Banks was also close to the French artist, Zoffany, whom he sought to join the Flinders mission, though unsuccessful.

Ironically, Banks’ greatest artistic achievement was the production of more than seven hundred lithographs from copper plates made from Parkinson’s drawings. They were to remain incomplete, seemingly abandoned after Solander’s death.

Science & The State: Banks and the Institutions

Kew and the King

Banks’ discoveries brought him close to King George III, as they both shared a mutual love of farming and agriculture. Banks would visit the King at his Palace at Kew for many years, touring the palace gardens. Banks was even instrumental in turning them into “Botanical Gardens” and becoming their first Superintendent.

Royal Society

Banks remained the longest serving President of the Royal Society, remaining in that post for more than forty years.

British Museum

Banks persuaded George IV, after the death of his father, George III, to bequeath his huge natural history library to the British Museum. The Kings Library is still in the museum today.

Natural History Museum

Resolution & Discovery

In addition to Banks’ botanic collections held in his Herbarium, it is thought that the custom built shelves and cupboards made for Banks’ Soho Square home are also in the Museum.

The Natural History Museum is also home to the famous “Florilegium” lithographic prints, made from the more than seven hundred copper plates produced by Banks of Parkinson’s famous botanic drawings. Given the immense volume of work, Parkinson often just sketched, and partially coloured his work. Because of Parkinson’s death, artists in London finished the work. But Banks never finished producing the copper plates; he didn’t even begin the final phase of the work, creating the colour lithographs from the plates themselves. This was finally done almost two hundred years later in the 1980s, when a joint venture between the Natural History Museum and Alecto Historical Editions, produced a hundred sets.

Linnaean Society

Banks was behind the deal that brought Linnaeus’ library and collection to Britain after his death. In 1786, after Linnaeus died, his family made contact with Banks in London seeking a home for his collection. Banks persuaded Smith, a wealthy landowner, to buy it. But the last minute attempt by the Swedish royal family to save the collection for the nation failed.

Royal Horticultural Society

Banks also had a role in the setting up of the RHS.

Convict Australia

Banks, more than any other individual, influenced the British Government’s decision to establish a penal colony in Sydney, known at the time as “Botany Bay,” after the American War of Independence put an end to the practice of sending convicts to the southern state of Georgia.

In the 1780s, Banks was one of the few people to have actually seen what was then known as New South Wales.

Re-Distributing The World’s Crops

Banks’ knowledge of plants, climate, and growing conditions in the newly discovered parts of the world, meant that he was perfect to oversee a government-sanctioned scheme of plant exchanges, designed to for the sole purpose of empowering and benefiting the British Empire.

Banks was behind the introduction of sheep to Australia, and many fruit and vegetable plants, which significantly altered the landscape of the country. He corresponded regularly with early Governors, exchanging notes on all aspects of the development of agriculture in the nescient colony, including how to keep plants alive on long sea journeys.

Banks And Race

One of Banks’ lesser-known activities was his role as an agent, assisting in the collection of heads of native peoples of the Pacific, including Aboriginal and Maori heads. Banks was a friend of the German anatomist, Johannes Blumenbach, who wanted the heads to assist in his study of race. In this pre-Darwinian age, naturalists, such as Linnaeus, believed there were different species of humans. Linnaeus, who introduced the words “Homo sapiens” to the world, speculated on the existence of a species he called “Homo Troglodytes,” which had a tail.

Blumenbach and others maintained there were different races, not species. Banks had heads of Aboriginal warriors delivered by royal courier to Blumenbach in Germany. An early Governor of NSW, Phillip Gidley King, sent Banks the head of Pemulwuy, a famous Aboriginal “freedom fighter,” who attacked British settlements and troops until he was captured and slain in 1803.

Banks: Patron Of Explorers

Bligh

Banks was the organising force behind many missions of discovery. The most famous was that of William Bligh, an accomplished sailor and navigator, who had been on Cook’s third and fateful journey when he was hacked to death in Hawaii. Banks nominated him for an expedition on board the “Bounty,” which would transport breadfruit plants from Tahiti to the West Indies, where it would be grown to feed the slaves.

The mutiny by the disgruntled crew led by Fletcher Christian is famous. The mutineers sailed the Bounty to distant Pitcairn Island where it was scuttled. Bligh was cast into an open boat with his colleagues, where he navigated and survived a perilous course across the Pacific to the East Indies.

When Bligh returned to England, he cleared his name, and was dispatched by Banks again to complete his mission; this time it was successful. The breadfruit plants landed in the East Indies, although its cultivation was never the success that Banks had hoped for.

Flinders

Mathew Flinders

Like Banks, Captain Matthew Flinders was from Lincolnshire. After a successful role on Bligh’s second mission, he was nominated by Banks to undertake a mission to circumnavigate Australia. In 1803, he successfully charted its coast. It was Flinders who gave the country its name. Tragically, Flinders was detained by the French in Mauritius on his way home at the height of the Napoleonic Wars and kept a prisoner for seven years. Finally released in 1811, he returned to London. He published the famous journal of his Australian discoveries, only to die days later; he was around forty years old.

Banks: The Collector

Banks was one of Britain’s greatest collectors of the 18th and early 19th centuries. Banks’ botanic collection was bequeathed eventually to London’s Natural History Museum. Banks’ collection, together with Sir Hans Sloane’s, which plants Sloane had established for the Chelsea Physic Garden, both formed much of the museum’s founding collection.

But Banks’ collections spanned interests far beyond botany, as Banks was a keen patron of the arts. Banks commissioned artists, such as Parkinson on the Endeavour mission, and Bauer and Westall on the Flinders’ mission that circumnavigated Australia, to depict the country’s nature and its inhabitants.

Banks’s also collected and looted cultural artefacts and objects from his encounters with Pacific Islanders, the Maori of New Zealand, the Australian Aborigines, and the natives of the East Indies.

Banks wanted to join Cook on his second mission to the Pacific in 1773, but fell out with the Admiral over his grand plan for the voyage; Banks insisted on an enlarged party, which included musicians. The Navy said Banks’ proposed redesign of “The Resolution,” would render the ship and the journey, unsafe. Banks had even made brass plates, and replicas of Maori clubs to give as gifts to iron hungry Pacific Islanders.

Final Years

In his later years, Banks was severely affected by gout that crippled him; he even had to be carried around. But he kept working to the end, fulfilling his duties as President of the Royal Society and promoting plant hunting expeditions across the globe.

In 1820, he died at his home in Spring Grove, at his mini estate on the outskirts of West London.

Lost Legacy

Banks died childless, which undoubtedly contributed to the breaking up of his Estate, in the decades after his death. A grandnephew on his wife’s side attempted to sell Banks’ private papers, almost a hundred thousand letters, to the British Museum, but the offer was declined. Thereafter, they were disbursed.

Banks manor house on his 20,000-acre estate at Revesby, in Lincolnshire, was destroyed by fire, and the estate passed out of the family.

Banks’ famous home at 32 Soho Square, London, which was an epicentre for scientific, cultural and social life in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, was demolished in the early 20th century. The new owner of his house in Spring Grove, near the Royal Botanic Gardens, a home where had Banks spent more than forty years, demolished it after it was sold.

Banks wanted neither monument nor anyone at his funeral. He was buried in a vault underneath St. Leonard’s Church at Heston Cemetery, in the outskirts of west London.