The Story Of Chocolate

Our love affair with chocolate began at least 4,000 years ago in Mesoamerica, in present-day southern Mexico and Central America, where cacao grew wild. When the Olmecs unlocked the secret of how to eat this bitter seed, they launched an enduring phenomenon.

Since then, people the world over have turned to chocolate to cure sickness, appease gods and show love. In fact, the making of chocolate has evolved into an industry so large that forty to fifty million people depend on cocoa for their livelihoods—and chocolate farmers produce 3.8 million tons of cocoa beans per year.

This study guide takes you from the ancient civilizations who first devised methods to eat cacao beans through its journey to Spain, the colonial owned slave plantations and into the factories of Pennsylvania, Broc and Yorkshire.

The Olmecs 1500 B.C.-100 B.C.

The Olmec’s, famous for carving colossal stone heads, were the first people known to process and eat cacao beans, which they called kakaw. They devised the fermenting, drying, roasting and grinding process that remain the basis of chocolate production as it is known today. The Olmec’s passed this knowledge down to the Mayans.

Mayans 1800 B.C.-1500 A.D.

Perhaps the first chocoholics, they referred to cacao as ‘food of the gods,’ and carved the shape of the pods into their stone templates, artwork, drinking vessels and even used the beans in human sacrifice as well as for medicinal purposes.

South-Western Americans 1000-1125 A.D.

The early Mesoamericans traded cacoa with their neighbours living many miles to the north. People living in northwest New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon drank cacao from cylindrical jars as part of ritualistic practices. The closest cultivated cacao grew in central Mexico.

Aztecs 1420 A.D.-1520 A.D.

While the Aztec royals continued the tradition of drinking cacao at ceremonies, they could not grow it in the central highlands of Mexico, so they too traded for it, with their southern neighbours the Mayans and others.

Aztec rulers also demanded that their tributes, an early form of taxation paid by citizens and those they conquered, be paid in cacao. In the communities themselves, cacao seeds were used as currency, traded at the market and kept locked up. A rabbit cost between four and 10 beans, a mule worth 50 and a turkey hen went for 100. In fact, cacao was so valuable in early times that it was counterfeited. People would hollow out the pods, fill them with dirt and pass them off as newly harvested.

Believing that the god Quetzalcoatl brought the cacao tree to them, Aztecs also used the beans as offerings to the gods. They also are said to have used chocolate to calm those who were about to become human sacrifice.

The scientific name Theobroma cacao was given to the species by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus in 1753, when he published it in his famous book Species Plantarum. He used Sloane’s text and drawings as the basis for descriptions of new species. Theobroma means ‘food of the gods’ in Latin, and cacao is derived from the Nahuatl (Aztec language) word xocolatl, from xococ (bitter) and atl (water).

Present day Chocolate culture

While cacao is no longer used as money, today it plays a central role in cultures around the world. Chocolate features in holidays and special occasions and to some extent still doubles as medicine.

Who Eats The Most?

In 2010, Switzerland led, at 22 pounds per person. Austria and Ireland followed at 20 pounds and 19 pounds. The United States comes in at 11th place, with Americans gobbling nearly 12 pounds apiece each year.

Special Occasions

In the United States, many of the chocolate dollars spent go toward celebrating holidays, to bring home Valentine’s hearts or Easter bunnies, Halloween candy and chocolate Santa’s.

In Mesoamerica, where humans first ate cacao, ritual use survives. In Mexico, hot chocolate may accompany festive foods for two Christian holidays, the 12 Days of Christmas and Candlemas. Mexicans also celebrate Dia de la Muertos (Day of the Dead) from October 31 to November 2 by giving balls, bars and drinks of chocolate to friends and family and honouring the deceased with chocolate offerings.

Medicinal Use

Throughout history, chocolate has been used to treat a wide variety of ailments—most commonly to help thin patients gain weight, to stimulate the nervous systems of feeble people, to calm those who are hyperactive, or to improve digestion and kidney function.

It is used as an ingredient in cosmetic ointments and in pharmacy for coating pills and preparing suppositories. It has excellent emollient properties and is used to soften and protect chapped hands and lips. Theobromine, the alkaloid contained in the beans, resembles caffeine in its action, but its effect on the central nervous system is less powerful. Its action on muscle, the kidneys and the heart is more pronounced. It is used principally for its diuretic effect due to stimulation of the renal epithelium; it is especially useful when there is an accumulation of fluid in the body resulting from cardiac failure, when it is often given with digitalis to relieve dilatation. It is also employed in high blood pressure as it dilates the blood-vessels.

The Spanish

At the start of the 16th century, Christopher Columbus had presented cacao beans from the Caribbean to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella as a curiosity, but they were considered them further. In 1519, the Aztec emperor Montezuma served chocolate drink to his new guest, the conquistador Hernando Cortes. The Aztecs thought that Cortes was the reincarnation of an exiled god-king. Instead, he had come-calling to find the much rumoured Aztec gold, and within three years he brought down the Aztec empire.

Cortes brought cacao to Spain in 1529 and sweetened the cacao drink for Spaniards, adding copious amounts of sugar that was unavailable in Mesoamerica. Before sailing home, he also planted cacao trees in the Caribbean. For nearly 100 years, Spanish aristocrats secretly enjoyed this new delicacy, adding cinnamon and vanilla to the sugar and serving it steaming hot. As the drink gained popularity, the Spanish planted more cacao trees across their colonies in Ecuador, Venezuela, Peru and Jamaica.

Soon after, the Spanish opened their first cocoa processing plant in 1580 and news of cacao was out, as it were and the use of cacao spread across Europe, the earliest uses recoded in France and Italy.

England

In 1672 Sir Hans Sloane details in the American Physician a medicinal recipe using milk in drinking chocolate and brings a cacao tree specimen back from Jamaica to England two years later in 1689. Whilst in Jamaica Sloane becomes interested in the bitter drink Jamaicans make by boiling roasted beans from a local tree in water. He believes it to have therapeutic properties but because the taste is unpalatable, he boils the beans in milk and sugar, creating the first milk chocolate drink—hot cocoa. He brings his recipe back to England and sells it to an apothecary who markets the product as “Sir Hans Sloane’s milk chocolate.”

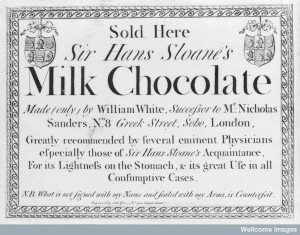

Trade-card ‘Sir Hans Sloane’s Milk Chocolate’

Soon after, William White sold it in his White’s Chocolate House and so, Sir Hans Sloane’s Milk Chocolate was launched. The Cadbury brothers later used the same recipe for over 35 years.

Upon Sloane’s returned to England in 1689. He published in two volumes the information he had gathered in Jamaica. This work contains careful and very readable descriptions of not only the plants and animals he encountered but also how natural resources were used by the islands’ inhabitants. Hans Sloane’s collections went on to found the British Museum, and his chocolate specimen can be seen on display in the Darwin Centre in the Natural History Museum in London.

The scientific name Theobroma cacao was given to the species by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus in 1753, when he published it in his famous book Species Plantarum. He used Sloane’s text and drawings as the basis for descriptions of new species. Theobroma means ‘food of the gods’ in Latin, and cacao is derived from Nahuatl (Aztec language) word xocolatl, from xococ (bitter) and atl (water).

The first official shipment of cacao beans arrived in Europe from the so called New World in 1585 and by early 17th century, it was all the rage in the palaces, mansions and monasteries of Baroque Europe, a mark of exquisite gentility. As the drink spread through the continent it was ever-more refined, drunk hot, sweet, and mixed with cinnamon. Surviving recipes give us cause to lament the powdery, watery froth that passes for hot chocolate in so many of London’s cafés and restaurants today! The Third Duke of Tuscany, also known as the gluttonous tyrant Cosimo de’ Medici, liked to take his chocolate infused with fresh jasmine flowers, amber, musk, vanilla and ambergris. No wonder chocolate was described in 1797 as the drink of the gods.

The impetus for London’s chocolate craze seems to have come from an unlikely quarter: France. In 1657, various newspapers were reporting that the public could sample, buy or learn how to make an ‘excellent West India drink’ called chocolate from a Frenchman, ‘the first man who did sell it in England’ at a chocolate house tucked away in Queen’s Head Alley in Bishopsgate Street, in the east of London’s business district.

For a city with little tradition of hot drinks (coffee had only arrived five years earlier), chocolate was an alien, suspect substance drink associated with popery and idleness (i.e. France and Spain); a market had to be generated. Within the next decade, a slew of pamphlets appeared proclaiming the miraculous, panacean – cure all – qualities of the new drink, which would boost fertility, cure consumption, alleviate indigestion and reverse ageing: a mere lick, it was said, would ‘make old women young and fresh, create new motions of the flesh’. For Samuel Pepys, chocolate was the perfect cure for a hangover, relieving his ‘sad head’ and ‘imbecilic stomach’ the day after Charles II’s bacchanalian coronation. The commonest claim, however — one inherited from the Aztecs and still perpetuated by chocolate companies the world over today — was that chocolate was a supremely powerful aphrodisiac.

The public was sold on this mendacious publicity campaign. Unlike in Paris and Madrid, chocolate drinking was not confined to the social elite; it was available in many of London’s coffeehouses (albeit in a more rough-and-ready and milky form than Cosimo’s brew) but since it was more expensive, and less of a caffeine hit, it was never drunk as widely. It was only around St James’s Square that a cluster of super-elite self-styled ‘chocolate houses’ sprouted and flourished.

Harvested in appalling conditions by African slaves in Jamaica, chocolate was thus consumed in one of the most exclusive addresses in Europe by the crème de la crème of British society, cementing chocolate’s association with decadence and luxury in the popular imagination.

The principal chocolate houses were Ozinda’s and White’s, both on St James’s Street, and the Cocoa Tree on Pall Mall. As befitted their location their interiors were a cut above the wooden, workmanlike interiors of the City coffeehouses, boasting Queen Anne sofas, polished tables, dandyish waiters and, at least in Ozinda’s case, a collection of valuable paintings for the customers to admire. It must have been unsettling for George I, the new Hanoverian King, to know that mere yards from the entrance to his palace, crypto-Jacobite’s were huddled together, sipping chocolate, and plotting his downfall. At the height of the Jacobite Rebellion in 1715, the king’s messengers burst into a packed Ozinda’s and dragged away its proprietor along with some of his customers as Jacobite traitors and incarcerated them in Newgate. Ostensibly, the Cocoa Tree was more respectable — in the early 18th century, it was the informal headquarters of the Tory party where policy and parliamentary strategy were concerted over chocolate and newspapers. Yet a significant wing of the party were crypto-Jacobite’s and it’s no surprise to read in the Manchester Guardian of 1932 that workmen drilling into St James’s Street discovered a secret underground passage (or ‘bolt hole’) leading from the site of the Cocoa Tree to a tavern in Piccadilly for Jacobite’s to flee to safety.

For what we might term ‘kamikaze gambling’, though, nothing compared to White’s Chocolate House and few London venues can have had such opprobrium heaped upon them by satirists and moralists. ‘Hell’, the inner gaming room at White’s, is depicted in the sixth episode of Hogarth’s Rake’s Progress in all its debauched glory (fittingly, it is also on fire, though few customers seem to notice or care). It is a picture of greed and despair; the posture of the ruined rake, hands held high as though for divine intercession, seems oddly prescient of Gericault’s Raft of Medusa except in White’s, everyone is an author of their own destruction rather than cast adrift on the mercy of nature.

The legendary White’s Betting Book, an archive of wagers placed between 1743 and 1878, by which point the chocolate house had evolved into a club, lends credence to Hogarth’s attacks. Much of the time it reads like a litany of morbid and bizarre predictions: ‘Mr Howard bets Colonel Cooke six guineas that six members of White’s Club die between this day of July 1818 and this day of 1819’, reads one typical entry (Colonel Cooke won). Elsewhere there are bets on which celebrities would outlive others; the length of pregnancies; the outcomes of battles; the madness of George III; the future price of stock; and whether a politician would turn up to the Commons in a red gown or not.

Yet middle-class moralists such as Hogarth were looking in on a world they didn’t understand and from which they were excluded. Just as Henry Jermyn’s St James’s Square was laid out in competition with the Earl of Southampton’s Bloomsbury Square, for the beau monde living in such close quarters, life was one big game of conspicuous consumption. To place the modern-day equivalent of £180,000 on the roll of a single die, as happened at the Cocoa Tree in 1780, may strike us as downright nihilistic but for the Georgian nobility it was a way of projecting their status, giving every meaning to their frequently idle, chocolate-guzzling existence.

White’s still exists today as a super-exclusive private members’ club at 37 St James’s Street with 500 members and a nine-year waiting list; supposedly the only woman ever to have visited is a certain Elizabeth Windsor in 1991. Yet lost its association with chocolate and indeed in London as a whole, traditional chocolate houses for “drinking chocolate, betting and reading the newspapers”, as one American visitor to eighteenth-century London put it, are few and far between.

What Is Cacao And Cocoa?

The cacao fruit tree, also known as Theobroma Cacao, produces cacao pods, which are cracked open to release cacao beans. From there, cacao beans can be processed a few different ways. Cacao butter is the fattiest part of the fruit and makes up the outer lining of the inside of a single cacao bean. It is white in colour and has a rich, buttery texture that resembles white chocolate in taste and appearance. Cacao butter is removed from the bean during production and the remaining part of the fruit is used to produce raw cacao powder.

Cocoa is the heated form of cacao that forms cocoa powder. Cocoa powder is produced similarly to cacao except cocoa undergoes a higher temperature of heat during processing. Surprisingly, it still retains a large amount of antioxidants in the process and is still excellent for your heart, skin, blood pressure, and even your stress levels.

The difference between dark, milk and white chocolate.

Milk chocolate is a solid chocolate made with milk (in the form of milk powder, liquid milk or condensed milk). The difference between dark chocolate and milk chocolate is that it does not have any milk solids added. Dark chocolate will generally have a higher percentage of cocoa solids and can range from 30% to 80% in cocoa solid make-up. Because of this, it is fuller in real chocolate taste and results in a drier, chalkier texture. Perhaps the most pronounced difference in taste is the deeper bitterness of dark chocolate which tickles the palette in aftertaste. Whereas milk and dark chocolate are produced from various proportions of the non-fat part of the cocoa bean, white chocolate contains no cocoa solids whatsoever. Instead, white chocolate is made from cocoa butter, a pale yellow edible vegetable fat, which has a cocoa aroma and flavour. Because cocoa butter doesn’t taste good on its own, milk, sugar and sometimes vanilla are added to deliver a sweet and creamy product.

Production And Process

Most of the world’s cocoa is grown in the narrow belt 10 degrees either side of the Equator because cocoa trees grow well in humid tropical climates with regular rain and short dry season. How is Chocolate produced? Chocolate is a product that requires complex procedures to produce.

Harvesting

Cocoa comes from tropical evergreen Cocoa trees, such as Theobroma Cocoa, which grow in the wet lowland tropics of Central and South America, West Africa and Southeast Asia.

Cocoa beans grow in pods that sprout off of the trunk and branches of cocoa trees. The pods are about the size of a football. When the pods are ripe, harvesters hack the pods gently off of the trees. Workers must harvest the pods by hand, using short, hooked blades mounted on long poles to reach the highest fruit. The pods are split open and the cocoa beans are removed. Pods can contain upwards of 50 cocoa beans each.

The beans undergo the fermentation processing. They are either placed in large, shallow, heated trays or covered with large banana leaves or simply heated by the sun. The beans are stirred to create equal fermentation. This process may take five or eight days to turn the beans brown. After fermentation, the cocoa seeds must be dried before they can be scooped into sacks and shipped to chocolate manufacturers.

Manufacturing Chocolate

Firstly, fermented and dried cocoa beans will be refined to a roasted nib by winnowing and roasting. Then, they will be heated and melted into chocolate liquor. Lastly blend chocolate liquor with sugar and milk to add flavour. After the blending process, the liquid chocolate will be poured into moulds. Finally the chocolate is wrapped and packaged.

Chocolate For The Masses

The new craze for chocolate enhanced the international slave market between the 1600s and 1800s as cacao plantations spread throughout the English, Dutch and French colonies. Due to the laboriousness of the production process, chocolate remained a luxury for the wealthy until the Industrial Revolution when steam-powered engines were introduced to speed the production of the bean.

As innovations were made to increase the speed of production, new techniques and approaches altered the texture and taste. In 1815, Coenraad van Houten, a Dutch chemist, introduced alkaline salts to chocolate to reduce its bitterness. In 1828, he created a press to remove about half the natural fat (cacao butter) from chocolate, making it cheaper to produce and more consistent in quality. Known as “Dutch cocoa”, the machine-pressed chocolate led to the transformation of chocolate to the solid form we know today. With Van Houten’s breakthrough, the British chocolate manufacturers, J.S. Fry & Sons, found a way to mix a blend of cacao powder and sugar with melted cacao butter instead of warm water. This produced a thinner paste, which could be cast into a mould. By the latter half of the nineteenth century, J.S. Fry & Sons were the largest chocolate manufacturers in the world, in part because they were the sole supplier of chocolate and cacao to the Royal Navy. But the firm always had to contend with its greatest rival Cadbury’s, who had released the first “chocolate box.” Chocolate confections had now become big business in Great Britain, Europe and in America. Many candy manufacturers now began using cocoa powder in liquid form to hand-coat sugar confections. Cocoa powder also became a widely used flavouring ingredient in cake, ice-cream and biscuit recipes.

Since the end of the 19th century, Switzerland has dominated the world of chocolate, and today its citizens are the number one consumers of the substance. The invention of true milk chocolate was a collaborative effort between Henri Nestle, a Swiss chemist who discovered a process to make powdered milk by evaporation in 1867, and Daniel Peter, a Swiss chocolate manufacturer who decided to use Nestlé’s powdered milk in a new kind of chocolate. In 1879 the first milk chocolate bar was produced.

Milton Hershey, “The Henry Ford of Chocolate Makers”, became a formidable rival to his European competitors, when he applied a version of mass production to the chocolate industry. Hershey’s mass-produced milk chocolate required huge amounts of milk and sugar. The milk was supplied by the 8000 acres of dairy farms, owned by Hershey, in the surrounding area. The sugar used in the Pennsylvania factory was supplied by Hershey’s sugar-mill in Cuba. Everything was mechanized, in true assembly-line fashion; by the late 1920’s, 23,000kg of Hershey’s cocoa was produced each day at the factory. The most famous and popular of Hershey’s products were the “Hershey’s Kisses” – bite-sized, individually wrapped, flat-bottomed drops of milk chocolate. By the 1980’s twenty five million Kisses were made daily.

More information:

Watch: The Story of… Chocolate