Bazaar: Treasures of the Islamic World

The Islamic World is full of unusual and fascinating treasures which reflect its rich and diverse culture, and also its interesting history.

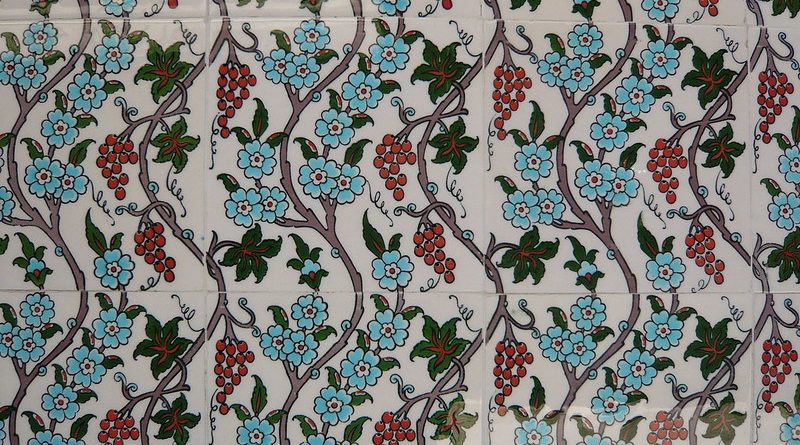

Iznik Tiles

One of Turkey’s most significant and iconic cultural exports, Iznik tiles are named for the eponymous Anatolian town. The tiles came into prominence during the heyday of the Ottoman Empire during the 15th Century. They are very much a symbol of the empire’s artistic peak and remain highly sought after and renowned for their beauty and craftsmanship. Iznik pottery is best recognised by its cobalt blue colour, believed to have been modelled after works of Chinese porcelain with influences from the Seljuk era also being evident.

The town of Iznik, small and inconspicuous by contemporary standards, emerged as a major pottery hub during the latter part of the 15th Century. While many historians initially believed the distinct style of pottery to be produced throughout the Ottoman Empire, evidence eventually revealed Iznik to be the central production hub. The town has a rich and extensive history of craftsmanship stretching back into its time under the Roman Empire as a major glass and ceramics production centre.

The massive spike in production and popularity, which occurred during the peak of the Ottoman Empire was inspired by a number of different factors. Interest in Chinese porcelain amongst the upper class was undoubtedly a major influence, which explains the tiles’ distinctive design. Indeed, Iznik tiles represented a synthesis of Chinese and Arabesque designs. The 16th Century represented a time of significant innovation in the production of Iznik tiles as new colours such as bole red and emerald green became more widely utilised. These colours, along with the initial Chinese-style blue-and-white, were the most commonly used amongst the most celebrated Iznik tiles.

During the 17th Century however, quality and production began to decline significantly and eventually Iznik ceased its role as the Ottoman Empire’s most revered producer of ceramics. It was succeeded by Kutahya, which became known for its own distinct variety of pottery. Iznik’s significant contributions to Turkish ceramics were swept aside for centuries, with many historians unaware of the extent of its importance for centuries. The industry declined to such a degree that information about means of production vanished entirely. The immense collection of ceramic works in the Topkapi Palace, which holds over 10,000 individual pieces, hardly has any Iznik works.

Interest resurfaced in Iznik ceramics following increasing Western influence in ‘Oriental artifacts and artworks’ during the 18th century. In modern times, interest in Iznik ceramics remains higher outside of Turkey but there have been recent initiatives to restore it to its previous cultural importance. The Iznik Tile Ceramic Research Centre and the Iznik Education and Training Foundation were set up in the 1990’s, reflecting an emerging desire within Turkey to engage with its rich cultural legacy.

Persian Carpets

One of the most iconic cultural and physical exports of the Persian Empire is the Persian carpet. The art of carpet weaving has been a significant aspect of Persian culture for millennia. Known for their heavy weight and varied utilities, Persian carpets are a unique standout amongst the broader category of Oriental rugs. The production of carpets remains a rare cultural constant throughout the region of Persia’s turbulent and extensive history.

The origins of Persian rugs can be traced back to prior to the Persian Empire when nomadic tribes used them as protective clothing from harsh weather conditions. The earliest known carpet, found in modern-day Siberia, dates back to the 5th Century BC and is currently housed in the Hermitage Museum. These carpets and their functions evolved throughout the region’s history. It is believed that the practice became a focal aspect of Persian culture following Cyrus the Great’s conquest of Babylon in the mid-6th Century BC. The King was blown away by the majestic nature of the city and attempted to imbue his Empire with its aesthetic beauty. He is subsequently credited by several historians for popularising carpet-making in the Persian Empire. This practice continued for centuries.

Persian carpet production increased significantly during the heyday of the Sasanian Empire, the Persian Empire’s final Kingdom. While an exact timeline of their production history is unclear, carpets became widely available throughout the empire’s territories. Following Persia’s conquest by the Islamic Empire and the region’s assimilation into the Islam religion, the Empire became sensitive to cultural change. Shortly afterwards, a hugely important development in the history of Persian carpets arrived with the brief Seljuk annexation of the Persian Empire. The Seljuk was a Turkish tribe with a rich heritage of carpet making. They introduced a number of important techniques, most notably the implementation of Turkish knots, which is still practiced by Persian carpet-makers in modern times.

Persian culture, following a brief period of oppression during Mongol occupation, eventually resurfaced and became more freely expressed than ever before, reaching new heights during the Safavid Dynasty in the 16th Century. It is this period which is considered to be the golden age of Persian carpets. The artistic richness of this period is arguably unmatched in Persian history. The rule of Shah Abbas is particularly considered to be influential in the development of Persian carpet design and production. With trade through the Silk Road routes in full swing, finer materials such as silk were more widely used. Larger workshops were introduced under the direction of the Shah, who saw Persian arts and design as a major symbol of cultural pride. This golden age came to an end following the Afghan invasion in 1722, which saw the destruction of the empire’s capital Isfahan. Persian carpet production entered another period of stagnation before resurfacing once more towards the end of the 19th Century.

Western interest became stimulated at the turn of the century and thus Persian carpets became a major export from the Middle East abroad. Despite the political turbulence in Iran during the 20th Century, this has done little to deter foreign interest in Persian carpets. In modern times, carpet making remains a vital Persian art, its cultural and historical significance still very much intact.