Children of Llullaillaco

Anyone visiting Argentina’s capital of the Northwest, Salta, cannot help but be struck by the sophistication and sassy elegance of its colonial architecture. With Cathedrals, apartment blocks, and government buildings ornate enough to rival the best Buenos Aires has to offer, but in a quarter of the space, Salta strikes that perfect balance between laid back small town charm and worldly grandeur rarely found outside provincial Capitals.

The city was founded in 1582 by the Spanish, and prospered as a trading post for mining projects in the northern Andes Mountains. Its situation on rich arable land also made it a centre for farming and food production.The architectural beauty of Salta’s old centre is a testament to its rich and aspirational past and draws visitors from far and wide. But one of the city’s most impressive sites has little to do with its Colonial heritage.

Salta’s Museum of High Mountain Archaeology offers one of the most extraordinary and disturbing exhibits of Inca relics in the world and will captivate anyone with even a passing interest in the ancient culture of the region. The Museum concentrates on items found high up in the Andes Mountains, a terrain regarded as holy by the indigenous communities that lived in the region hundreds of years ago.

Most of the relics on display are items relating to holy burial sites and sacrificial offerings made some 500 years ago when much of South America was part of the Inca kingdom. The highlight of the exhibit, without doubt, are the mummified bodies of three Inca children who were entombed beneath rocks at the top of a 22,000 foot high mountain called Llullaillaco.

Collectively they are known as the Children of Llullaillaco and one of them is always on display at the museum at any one time. Thanks to the bacteria busting qualities of the cold high altitude air they are considered the best preserved mummies in the world.

The eldest child, called the Maiden, is believed to have been 15 years old when she died of cold on the mountain top. The other two, a boy known as El Nino and a girl called the Lightning Girl, because her body is believed to have been struck by lightning sometime after her death, were just about 7 and 6 years old respectively.

Discovered in 1999 beneath a pile of rocks, a customary entombment at the time, the children quickly found their way to the Museum where they have been kept cryogenically refrigerated, even when on display.

The level to which these children are preserved is alarming, you may want to brace yourself before entering the room where they are exhibited. But the experience is compelling for those able to fight off squeamish impulses.

The bodies are completely intact with all their original hair, teeth and skin, their last meal still undigested in their stomachs. The expressions on their faces are eerily life like and in the case of The Lightning Girl, whose face seems frozen in agony, profoundly distressing.

The clothes they wear, intricately woven with colors as fresh as if they were made yesterday, are also unbelievably well preserved and fine examples of high Inca craftsmanship. In fact it is the clothes that tell us much about who these children were. The young boy’s clothing is believed to have been stitched by a select group of maidens chosen especially for the occasion, his head adorned with regal plumage.

There is little doubt these children were special, carefully selected for their beauty and perfection, from the highest stratum of Inca society, sometimes children of the Emperor himself were chosen, to serve as sacrificial offerings to the Gods in a ceremony known as a Capacocha.

Human sacrifice in Inca society was not as common as one might think. Animal and object offerings were far more routine. Human sacrifice was special and done in times of crisis or acute need. The victims high social standing was proof they were the best the society of the time had to offer. There would be no skimping to appease the Gods in critical times. These kinds of human sacrifice were likely done when an old ruler had died and a new one came to power, or in times of severe drought or natural disaster, times when blessings from the Gods would be especially needed.

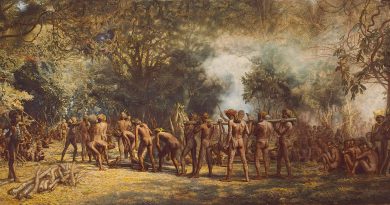

The story of the Llullaillaco Children’s final days is extraordinary. Before being sacrificed they were taken in grand procession from their home town, across the kingdom to the Inca capitol of Cuzco where they were presented to the Emperor and celebrated with feasts and great public ceremony. Then the children and their ceremonial entourage continued their journey, on foot, from Cuzco to the chosen place of their sacrifice. In this case it was hundreds of miles away and the whole tour is thought to have taken about a year to complete.

In Inca society, to be selected was considered a great honour, a privilege that would transform those chosen into Gods, enabling them to watch over their people for eternity. For the families of these children, and some gladly offered them up, it was also a prestigious act securing them an elevated place in society.

No doubt these children were indoctrinated to believe in the glory of their role as were their parents, but they were still children and it’s difficult to imagine what they must have felt as they prepared for the transformation. No matter how much brain washing they might have undergone for this ultimate sacrifice it’s hard to believe their final hours, after the celebrations and pomp had faded away, were happy ones.

Upon reaching the mountain top they would be drugged up on a corn based alcoholic drink called Chicha. This would have a calming effect and was probably designed to put them to sleep before the entombment began. They were sealed in the tomb along with some beautifully crafted trinkets and talismans, and left to die of cold. One can only imagine the horror of waking up, inebriated and freezing to death, alone in the darkness of such a tomb. Let’s hope they were unconscious to the end.

Archeologists are not convinced all three of the Llullaillaco Children were sacrificed at the same time, but those that do suggest that two of the children, the little boy El Nino and one of the girls, may have been symbolically married with the third girl present as a chaperone.

Whatever the specific details of their death, the museums atmospheric exhibit of the children and their ceremonial trappings is respectful and moving. Nevertheless, the display of the children’s bodies has become a subject of controversy. Some feel it a desecration and demand the children be returned to their original resting place. Interestingly many local indigenous communities are not the ones leading the campaign to have the children returned and the Museum quite reasonably argues that now that the site of the tomb is known, if the children were returned to it, they would be stolen.

This is not just speculation either. In another part of the museum is a heavily ravaged mummy known as the Queen of the Hill. She was stolen from her resting place atop another mountain by fortune seekers who subsequently dragged her around the country trying to make money off of her deteriorating corpse before it was eventually rescued by the Museum.

In the case of the Llullaillaco Children, their display attracts a wide range of visitors to the museum, not all of them tourists. Some visitors still regard them as Gods and come to prey and ask them for blessings. Some chant and perform ritualistic music, others believe one day the children will wake up. Whatever the view, for many in the region, the children provide an important continuity with the past, a representation of the potent connection between the modern world and the eternal.

For now at least, it seems the children are better off in the chilly freezers and display cabinets of Salta’s High Altitude Museum, safe from the grubby hands of treasure hunters, where they can provide visitors with an illuminating and emotionally engaging window onto the cultural practices of one of the world’s great ancient civilizations.

Visitor Information:

Museo de Arqueología de Alta Montaña (High Country Archaeology Museum)

http://www.maam.gob.ar/

Mitre 77, Salta 4400, Argentina

54 387 437 0499