Great Explorers: Africa

Despite having contact with northern Africa for millennia, European knowledge of the continent’s sub-Saharan region was minimal at best until the early 19th Century. Despite accomplishments during the Age of Discovery, little was known about the vast continent. A number of eager explorers from all over the world became drawn to it, enticed by its untapped potential, with their exploits triggering the controversial Scramble for Africa as various European powers contested for territorial colonisation.

Richard Francis Burton

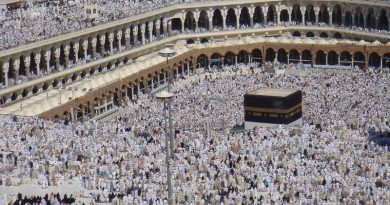

One of Britain’s most iconic and individualistic explorers, Richard Francis Burton was a true polymath. Known for his immense linguistic capabilities, he was believed to have been able to speak 29 different languages. Truly fascinated by other cultures, he was known for conducting detailed examinations on a number of different societies with which he engaged. Major feats of his included a translation of iconic text ‘One Thousand and One Nights’ and a journey to Mecca at a time when this was forbidden to Europeans. He is perhaps best known as being, along with John Hanging Speke, the first European to travel to the Great Lakes of Africa. Funded by the Royal Geographical Society, he arrived in Zanzibar in 1856 on a search for the source of the River Nile. Despite contending with disease and exhaustion, the two explorers surveyed a wealth of lakes including Lake Victoria and Lake Tanganyika. Burton and Speke fell out following this journey over credit and debt issues. Burton was known as a maverick and sometimes controversial figure, known for rejecting the standard stances on colonialism and British ethnocentrism. He was also known for his interest and purported participation in a number of taboo sexual acts, particularly those of foreign cultures. One of the most unique figures in the canon of European explorers, he was a true outlier.

John Hanning Speke

An associate turned rival of Burton, John Hanning Speke’s career and life were defined by his three expeditions to discover the source of the River Nile. Taking part on Burton’s expedition, he broke out on his own following their joint discovery of Lake Tanganyika in 1858. He discovered Lake Victoria during this detour and put forward the view that this was indeed the source of the Nile, which Burton rejected and the Royal Geographic Society regarded with disbelief. Speke conducted two more expeditions. He found himself eclipsed by the accomplishments of the more charismatic and popular Burton. The two were scheduled for a debate regarding the source of the Nile. However, Speke was killed in a hunting accident the day before by his own gun. Historians are divided as to whether it was the result of an accident or suicide. Most favour the former although a still-spiteful Burton promoted the latter. After his death, Morton Stanley proved that Speke’s hypothesis was indeed correct.

David Livingstone

Arguably Britain’s definitive African explorer, David Livingstone has a high position amongst the icons of exploration, enjoying an almost mythical status amongst his contemporaries. Born and raised in Scotland to a working class family, he moved to London to study medicine and became enamoured with the prospect of travelling as a missionary to Africa. Known for his Christian values, keen scientific mind and vehement opposition to slavery, religion was a major motivating factor in Livingstone’s exploration of Africa. He felt it was his purpose in life to expound the teachings of Christianity. During his travels in the mid-19th Century, he played an instrumental role in consolidating and expanding western knowledge of African geography, discovering and naming Victoria Falls and becoming the first European to traverse the width of Southern Africa. Upon his return he was greeted as a hero, with many appreciating his accomplishments and his rags-to-riches narrative. He continued his explorations of Africa whilst dedicating his time to criticisms of the barbaric slave trade and attempting to find the source of the Nile. He ultimately died on his final expedition, encountering fellow explorer Henry Morton Stanley when near his death.

Henry Morton Stanley

Picking up where the iconic Livingstone left off was the Welsh-American Henry Morton Stanley. Known for his iconic greeting: ‘Dr Livingstone I presume?’, Morton Stanley was a vaunted explorer in his own right, albeit a far more controversial one. Born and raised in Wales before making a name for himself as a soldier during the American Civil War, he then became a journalist for the New York Herald. Made famous for his successful search for Livingstone, he went on to become a major African explorer. He charted much of Central Africa and saw the potential of the Congo region as a colony, a proposition rejected by the British. He played a major role in its annexation by King Leopold II of Belgium and was known for his brutal techniques of coercive labour. Although he was knighted and found success later in life, retrospective views of Stanley have been far less flattering. Critics draw attention to his cruelty and racist views of Africans. He is believed to be an inspiration in Joseph Conrad’s iconic novel ‘Heart of Darkness’.

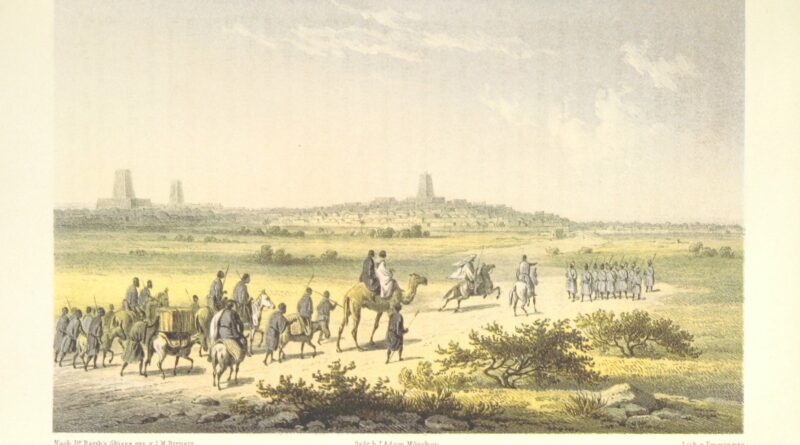

Heinrich Barth

A German explorer, Barth is widely considered to be one of the most important European explorers of the African continent. Like Burton, he was known for his academic background and proficiency with languages. He had a diplomatic approach to his profession, establishing links of friendship and respect with a number of African rulers. Upon his return, he had travelled a vast distance of over 10,000 miles and recorded accurate routes for future travellers. His travelling accounts have been cited by a number of scholars. He remained an active traveller, visiting Asia Minor and Turkey, although it was his African exploits for which he is best known.

Frederick Russell Burnham

An American explorer with an illustrious life filled with adventure. A major figure in the establishment of the Scouting Movement, Burnham was born on a Sioux Indian Reservation in the state of Minnesota, before travelling West where he experienced the final years of the American frontier. Relatively uneducated, he fought in the Apache Wars on the behalf of the United States Army before travelling to Africa in search of more adventure. He served on the behalf of the British military, fighting in a number of conflicts in South Africa and Rhodesia. His most famous military exploits came during the Second Boer War. In later life, he found wealth in the booming oil industry.

Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza

An Italian-born explorer, Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza was best known for his alliance with the French. He established the French colony the Republic of Congo with its capital city of Brazzaville named after him. He also extensively travelled around modern-day Gabon. He served as the colony’s Governor-General for a number of years but was dismissed due to falling profits. He became disillusioned by colonial repression and exploitation and distanced himself from colonialism thereafter. In 1905, he returned to investigate stories of brutal oppression of the natives by his replacement Emile Gentil. His heavily critical report was quashed out of national embarrassment. He died on his return home in Dakar, the capital of modern-day Senegal. His body was returned to France but eventually buried in Algiers.

Mungo Park

A Scottish explorer, Mungo Park came from an upper-middle class upbringing and was educated a a surgeon before making a name for himself as an explorer. Cutting his teeth in the East Indies, his studies of the fauna in Sumatra earned him scientific plaudits and enabled him to embark on an expedition to Africa, following the course of the Niger River, being the first Westerner to do so. His journey was fraught with obstacles and he was nearly killed by fever, which left him bedridden for months. His account ‘Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa’, published upon his return in 1797, earned considerable acclaim. He returned to Africa in 1805 to lead another expedition comprised of 40 men. By mid-August, there were only 11 survivors. He continued the journey to his death, unwilling to return back. Years later, his fate was revealed. Following an incursion with a local tribe, he fell into the river and drowned.