Great Railway Stories of Scotland

Glasgow to Mallaig & The Jacobite

In 2013, a famous Spanish tarot card reader predicted Scottish independence the following year, a vision that was greatly welcomed by the Scots, as they themselves believe in the gift of “Second Sight” that was handed down through certain Scottish families and produced a range of famous seers in the medieval ages and beyond. Ironically, most people around the globe already consider Scotland to be independent, courtesy to William Wallace and Mel Gibson’s Braveheart, thedistinct Scottish accent, way of dress, Nordic mentality and their ongoing vocal discontent of Downing Street and Buckingham Palace.

Numerous myths and legends surround the upper third of the British isle, covering historical facts and figures in a numinous mist that is so typical for the land, which was settled as early as 10,000 BC. It became a prominent in the history books only with the arrival of the Roman Empire, and since then suffered the standardfate of other European lands – blood and battle, defeat and victory, union and division. The Scottish shores were a primary landing spot for the Viking tribes of Denmark and Norway, who settled on the island eventually in the 11th century and merged their culture with the existing Anglo-Saxon culture. The best-known parts of Scottish history, however, begin with its Wars of Independence in the 13th and early 14th century, and the nostalgic sounds of Scottish bagpipes remind one of William Wallace’s tragic fate and the unfulfilled promise of freedom.

In the mid-18th century, Scotland was still a very rural, agricultural economy, poverty-stricken and with a low life expectancy of the lower, serving class. James VI of Scotland, from the House of Stewart, had been crowned King of England in 1603 and the Stuarts reigned over both Scotland and England until the death of Queen Anne 1714. King James VII was forced to abdicate in favour of his daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange, after he had turned to Roman Catholicism, which had sparked an outrage amongst the Protestants. James fled to France seeking support, and Prince William took the throne, something that a group of resistance fighters and devoted followers of James and his son Charles Edward Stuart (‘Bonnie Prince Charles’) would never forgive and accept.

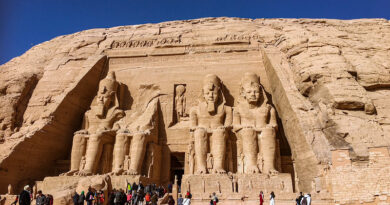

These followers became known as the Jacobites (James reads Jacobus in Latin), and their uprisings between 1688-1746 are equally admirable as they were unsuccessful. Although many Jacobites came from the Western Highlands, it was a mix of highlanders and lowlanders, French and Irish, who supported the rebellions, before finally being defeated in the Battle of Culloden in 1745. It became treason to openly support the Stuart claim to the throne after the battle, so supporters and loyal friends of Bonnie Prince Charles produced a secret ritual involving a secret portrait of the Prince, which only strengthened the romantic, secretive notion of the rebellion. They would raise their glasses in a toast to a tray holding a silver goblet with the portrait of Bonnie Prince Charles elegantly painted on its lower middle part, once servants and ladies had withdrawn from the dinner table; if there was danger of interruption, the setup could easily be dismantled and hidden away. The goblet can be found in a small museum in the Western Highlands, along the route of the Jacobite train, named in honour of West Highlanders supporting the Stuart claim. The small town itself is named after William of Orange, and was famously besieged for two weeks by Jacobites, who had taken the other two forts nearby, but failed to conquer Fort William.

The first bits of this particular railway line, part of the West Highland line, were cut with a silver spade in October 1889, more than a century after the rebellion and it was yet another significant landmark in the transformation of a whole land during the industrial revolution with Scotland growing more prosperous by the day. The Scottish population had suffered greatly in the beginning of the 19th century, with a major Cholera epidemic killing 10,000 people in Scotland alone. At the time, it was poverty-stricken and unemployment was high; the few railways that had been built, were mainly for the benefit of the industry transporting coal and raw materials between the main commercial centres, Glasgow, Edinburgh and Dundee. The northern parts remained isolated and continued to live an agricultural life based on farming and fishing. However, when Victoria took the throne in 1837, it triggered a turn-around for the entire kingdom, almost as if a magic wand had been waved, and only one generation later the entire Scottish railway had been built.

In 1842, the Edinburgh and Glasgow line opened andpopularity of train travel skyrocketed. The Caledonian company, which had been running the trains to Glasgow from London, suddenly found itself in a fierce competition with the Edin-Carlisle company for future construction of railway and control of railway territory. The advent of railway opened up areas of the country previously out of reach – holidaying in the West Highlands for a growing upper middle-class was suddenly an achievable dream. The Victorian age upgraded the standard of living greatly, less work meant more leisure time, increased income better food, better hygiene and of course – travel.

Glasgow shot up the ranks to become the second most important city in the Empire; designed as a centre of commerce along the lines of NYC, it was built to a grid plan that simultaneously mirrored the class-consciousness of the Victorian society. Posh up on the hill, run-down quarters on the outskirts. Many English entrepreneurs made their way up north, as Scottish labour proved cheaper than the English; they engaged in cotton manufacturing, ship building and heavy engineering enterprises. The upper class had developed an equally lavish lifestyle as elsewhere in the kingdom, rum, sugar and tobacco was imported from the colonies; the “industrial giant” of the time generated a new city for better and for worse – wealth, increasing entertainment and splendid architecture on the one hand, a huge working-class and pollution on the other. Glasgow was somewhat forgotten for several decades in the 20th century before it experienced a cultural renaissance, and its strategic importance for the rise of wealthy Scotland was remembered.

Glasgow is the starting point of the West Highland line, one out of two railway lines that access the mountainous and remote west coast of Scotland. It is a single line track that was built in several sections during the 19th century. There are usually significant delays due to the trains having to wait at stations with crossing loops for opposite trains to run past. The train leaves suburbia of Glasgow and the scenic part of the journey begins after Garelochhead at the Gare Loch, and it thenpasses Crianlarich and then Tyndrum, the smallest place in Scotland to boast two railway junctions. The tiny village is built over the battlefield where Clan MacDougall defeated Robert the Bruce and snatched the legendary Brooch of Lorn, one of three West Highland silver turreted brooches centred on charmstones. The train continues then to Oban, and onto Fort William, before finally reaching Mallaig, whose bustling port is the ferry terminal for the romantic Isle of Skye. The route has been praised as the most scenic train ride in the world, set against a haunting and magnificent landscape that only 130 years ago was hardly accessible for the public.