Pitcairn Island

The history of the Pitcairn Islands begins with the colonization of the islands by Polynesians in the 11th century. The Polynesians established a culture that flourished for four centuries and then vanished. Pitcairn was settled again in 1790 by a group of British mutineers of the HMS Bounty and Tahitians.

When the Bounty mutineers arrived on Pitcairn, it was uninhabited. However, they found the remains of an earlier Polynesian culture that had since vanished. Archaeologists believe that Polynesians lived on the island from the 11th to the 15th century. These first Pitcairners seem to have operated a trading relationship with the more populous island of Mangareva, 250 miles to the west, in which food was exchanged for the high quality rock and volcanic glass available on Pitcairn. It is not certain why this society disappeared, but it is probably related to the deforestation of Mangareva and the subsequent decline of its culture; Pitcairn was not capable of sustaining large numbers of people without a relationship with other populous islands.

Thus, the island was uninhabited when it was discovered by Spain by the Portuguese explorer Pedro Fernández de Quirós in January 1606. It was rediscovered by the British on 3 July 1767 on a voyage led by Captain Philip Carteret, and named after Robert Pitcairn, the crew member who first spotted the island. Pitcairn is one of the sons of John Pitcairn.

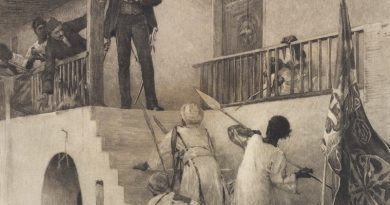

On January 15, 1790, the mutineers of Bounty and their Tahitian companions arrived on the island. The group consisted of Fletcher Christian and eight other mutineers from the Bounty. These were Ned Young, John Adams, Matthew Quintal, William McCoy, William Brown, Isaac Martin, John Mills and John Williams. Also with them were six Polynesian men and twelve Tahitian women, as well as a Tahitian baby girl named Sally, daughter of one of the women, who would become a respected person in the community. The settlers took everything off the Bounty and then burnt the ship to hide all trace of their existence.

Though the islanders learned to survive quite comfortably by farming and fishing, violence and illness caused many problems. Much of the violence was caused by some of the mutineers and the Polynesian men wanting the same women, there being fewer women than men. Two of the women died in accidents in 1790, exacerbating the problem. Another problem was that when the land was divided between the families, the Polynesian men were not given any property and were treated like slaves by some of the mutineers, particularly Williams and McCoy. Two of the Polynesian men were killed by another Polynesian man, by order of the mutineers. The violence culminated one day in September or October 1793, when all four of the remaining Polynesian men attempted to massacre the mutineers. Martin, Christian, Mills, Brown and Williams were killed. The Polynesian men soon began fighting among themselves, however. One was killed during this fight, another was killed by one of the women, one was killed by Quintal and McCoy and a final one was killed by Young. This murder of nearly half of the island’s population dramatically changed the community. With many of the mutineers having children with their wives, women and children began to outnumber the men. The women became dissatisfied and tried to leave the island. When this failed, they attempted to kill the men, but they eventually became reconciled.

Soon, Young and Adams, who began to assume leadership of the community and help the women and children as much as possible, drifted apart from Quintal and McCoy, particularly after McCoy discovered how to brew alcohol from a local plant. McCoy committed suicide while drunk in 1798, and Quintal was killed by Adams and Young in 1799 after he threatened to kill the entire community. Shortly thereafter, Young and Adams became interested in Christianity, and Young taught Adams to read using the Bounty’s bible.

After Young’s death from asthma in 1800, John Adams was the only mutineer left alive on Pitcairn. Several ships had apparently discovered the island during the 1790s, and one even landed to pick coconuts, but these ships did not encounter the community. The community’s first contact with a foreign ship came in 1808 when an American ship, the Topaz commanded by Mayhew Folger, landed on the island. The captain and crew were impressed by the community. They updated Adams and the growing population of women and children on the events in the world of the past 20 years, and promised to tell the world about what had happened to them. By this time, Adams had set up a school for the island’s children, in which the teaching of Christianity was an important part. He was known as “father” by all members of the community.

In 1814 the Royal Navy discovered the existence of the colony. They were favourably impressed by the islanders and felt it would be “an act of great cruelty and inhumanity” to arrest John Adams.

The Pitcairners continued to be contacted more often by ships. During the 1820s, three British adventurers named John Buffett, John Evans and George Nobbs settled on the island and married children of the mutineers. Following Adams’s death in 1829, a power vacuum emerged. Nobbs, a veteran of the British and Chilean navies, was Adams’s chosen successor, but Buffett and Thursday October Christian, the son of Fletcher and the first child born on the island, who had the task of greeting visiting ships, were also important leaders during this time.

In 1831, the islanders temporarily abandoned Pitcairn to immigrate to Tahiti. Six months later they returned to Pitcairn aboard the ship of William Driver, the American sea captain who’d coined the term “Old Glory” for the US Flag. He agreed to take aboard these descendants after learning they were unable to become accustomed to their new home, and a dozen people, including Thursday October Christian, had died of disease.

The islanders were now even more leaderless, as alcoholism became a problem and Nobbs was unable to gain enough support. In 1832, an adventurer named Joshua Hill, claiming to be an agent of Britain, arrived on the island and was elected leader, styling himself President of the Commonwealth of Pitcairn. He ordered Buffett, Evans and Nobbs to be exiled, banned alcohol and ordered imprisonments for the slightest infractions. He was eventually driven off the island in 1838, and a British ship captain helped the islanders draw up a law code. The islanders set up a system whereby they would elect a chief magistrate every year as the leader of the island. Other important positions on the island were those of schoolmaster, doctor and pastor. Nobbs, however, was the effective leader of the island. Under this law code, Pitcairn became the first British colony in the Pacific and also the second country in the world, after Corsica under Pascal Paoli in 1755, to give women the right to vote.

By the mid-1850s the Pitcairn community was outgrowing the island and they appealed to Queen Victoria for help. Queen Victoria offered them Norfolk Island, and on 3 May 1856, the entire community of 193 people set sail for Norfolk Island on board the Morayshire. They arrived on 8 June after a miserable 5 week trip. However, after 18 months, 17 returned to Pitcairn and in 1864 another 27 returned.

In 1858, while the island was uninhabited, survivors of the Wild Wave shipwreck had spent several months there until rescued by USS Vandalia. These visitors had dismantled some houses for wood and nails and had vandalised John Adams’s grave. The island was also nearly annexed by France, whose government did not realize that the island had just been inhabited. George Nobbs and John Buffett stayed on Norfolk Island. By this time, the American Warren family had also settled on Pitcairn Island.

During the 1860s, further immigration to the island was banned. In 1886, most of the island left the Church of England and converted to the Seventh-day Adventist Church after receiving literature from that religious group. Missionaries arrived on the island a few years later, and the conversion of an entire community became a great propaganda boost for the religion. Important leaders of Pitcairn during this time were Thursday October Christian II, Simon Young and James Russell McCoy. McCoy, who was sent to England for education as a child, spent much of his later life on missionary journeys. In 1887, Britain officially annexed the island, and it was officially put under the jurisdiction of the governors of Fiji.

During the 20th century, most of the chief magistrates have been from the Christian and Young families, and contact with the outside world continued to increase. In 1970 the British high commissioners of New Zealand became the governors of Pitcairn. Since May 2010 the governor has been Victoria Treadell. In 1999 the position of chief magistrate was replaced by the position of mayor. Another change for the community is the decline of the Adventist church, where there are now only 8 regular worshippers.

Since a population peak of 233 in 1937, the island is suffering from emigration, primarily to New Zealand, leaving a current population of 45.

Currently, the continued existence of the colony is threatened by allegations of a long history and tradition of sexual abuse of girls as young as 10 and 11. On September 30, 2004, seven men resident on Pitcairn, and a further six now living abroad, went on trial facing 55 charges of sex-related offences. Among the accused was Steve Christian, Pitcairn’s Mayor, who faced several charges of rape, indecent assault, and child abuse. On October 25, 2004, six men were convicted including Steve Christian. A seventh, the island’s former Magistrate Jay Warren, was acquitted.