A Short History of the English Garden

There had been gardens in England since Roman times but the grand villas of the ancient world were a world away from the medieval castles of England which were modelled on those of its Norman invaders.

It wasn’t until Tudor Times that the English sought to tame the landscapes around them for ornamental rather than agricultural reasons. Influences from Renaissance Italy began to infiltrate Tudor gardens, such as those at Hampton Court Palace, home of Henry VIII.

The most recognised feature from this period is the knot garden; a geometric bed of interlacing patterns designed to be seen from above and filled with herbs and favourite flowers such as carnations. Hampton Court also featured wilder landscapes such as deer parks which were living larders providing meat for the household and also a symbol of wealth and status.

The main development of gardens in the Stuart period is the scale as they were influenced by the vast formal gardens of France, such as those at the Palace of Versailles, and later, in a more sober fashion, Holland.

These gardens were designed to be symmetrical with long axial walks and rides stretching into the woods and parks beyond, resulting in the advent of the avenue.

Great expanses of water were brought to life by dancing fountains or pleasure boats. Topiary was used to create formal shapes out of evergreen shrubs in the ultimate expression of man’s control over nature.

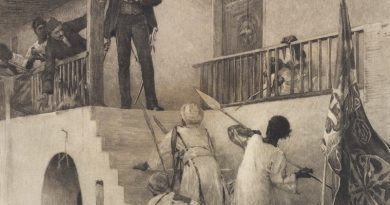

The gardens at Ham House, in West London by the Thames are a model of this style. Built in 1610, the house was gifted to his whipping boy, William Murray, by Charles I in 1626.

The English garden, which developed in the 18th-century, originated as a revolt against the architectural garden, which relied on rectilinear patterns, sculpture, and the unnatural shaping of trees.

The revolutionary character of the English garden lay in the fact that, whereas gardens had formerly asserted man’s control over nature, in the new style, man’s work was regarded as most successful when it was indistinguishable from natures.

The gardens at Castle Howard in Yorkshire and Chiswick House in London offer examples of this style. They exhibit influences obtained during the Grand Tour of Europe in the 18 century undertaken by English gentlemen.

Chiswick House, for example, shows characteristics of ancient classical gardens: a river, grotto cascade, hedges exedra with statues, said to be from Hadrian’s villa and a garden house and pool with obelisk.

In the architectural garden, the eye had been directed along artificial, linear vistas that implied man’s continued control of the surrounding countryside. In the English garden, however, a more natural, irregular formality was achieved in landscapes consisting of expanses of grass, clumps of trees, and irregularly shaped bodies of water.

William Kent was responsible for beginning the wholesale transformation into the new fashion. A classic example was at Stowe in Buckinghamshire, where the greatest of England’s formal gardens was by stages turned into a landscaped park under the influence of Kent and then of Lancelot Capability Brown.

Brown’s contribution was to simplify the garden by eliminating geometric structures, alleys, and parterres near the house and replacing them with rolling lawns and extensive views out to isolated groups of trees, making the landscape seem even larger. Brown sought to create an ideal landscape out of the English countryside. He created artificial lakes and used dams and canals to transform streams or springs into the illusion that a river flowed through the garden.

He compared his own role as a garden designer to that of a poet or composer. Brown designed 170 gardens; among the most important were Petworth (West Sussex) in 1752; Chatsworth (Derbyshire) in 1761, Bowood (Wiltshire) in 1763 and Blenheim Palace (Oxfordshire) in 1764.

English fascination with gardens in Victorian times led to public gardens such as the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. Gardens also grew partially through an interest in plants and botany in particular.

Sir Hans Sloane rescued the Chelsea Physic Garden in 1722. It was established in 1673 by The Society of Apothecaries, for teaching students pharmacological uses of different plants, hence the name “physic”.

Sir Joseph Banks pioneered the development of Kew Gardens with his friend, George III, showcasing exotic species discovered during the Age of Exploration.

Caring for these new plants in a temperate climate led to the erection of some of the world’s first greenhouses and conservatories.

The first “orangeries” were built as a means for protecting delicate orange and other citrus trees from the extreme winter temperatures. As the size of the structures grew, so did their use change to one of entertaining guests at garden parties, flower shows or other social engagements.

Four conservatories were designed for Buckingham Palace by architect John Nash in 1825. However with the remodelling of the Palace for William IV, these were moved. One of the famed four was moved to Kew and still stands today.

With the migration of Victorian architecture to the rest of the world at this time, many large cities with European populations began building public conservatories. These buildings hosted flower shows or displayed rare and wonderful tropical plants to audiences in colder climates.

Through the ages garden designs have come in and out of fashion. In the 19th century there was a revival of the Italianate garden which can be seen in many English stately homes today.

But then in the 19th and early 20 centuries, English garden designers such as Gertrude Jekyll partnered with leading architects including Edward Lutyens to create the classic English arts crafts garden such those at Hestercombe in Somerset which rebelled against the trend for stiff Victorian gardens, and celebrated a variety of colours and plants combined with a variety of the styles. This idea was developed further in the 20th centuries at the gardens at Great Dixter by Christopher Lloyd and at Sissinghirst, also Kent by Vita Sackville West.

Written by Ian Cross, edited by Kaz Bosali