The New Silk Road: Economic Imperialism in the 21st Century

In the half dozen years since President Xi Jinping announced his grand plan to connect Asia, Africa and Europe, the Belt and Road Initiative has morphed into a broad catchphrase to describe almost all aspects of Chinese engagement abroad and foreign direct investment.

Literally speaking, the Belt and Road Initiative, or yi dai yi lu, is a “21st century silk road,” confusingly made up of a “belt” of overland corridors and a maritime “road” of shipping lanes by which China aims to build its trading relationships with the rest of the world.

From South-east Asia to Eastern Europe and Africa, Belt and Road includes 71 countries that account for half the world’s population and a quarter of global GDP. The Belt and Road project has a targeted completion date of 2049 which coincides with the 100th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China.

The Belt and Road Initiative is expected to cost more than one trillion dollars with Chinese firms engaging in construction work across the globe on an unparalleled scale, and in the name of development for some of the world’s poorest nations.

Critics say China’s dominance in the construction sector comes at the expense of local contractors in partner countries. It is reported that Chinese firms have secured almost 500 billion dollars (half of the expected cost of the entire initiative) in contracts to complete the work. They say the vast sums raked in by Chinese firms are at odds with the official rhetoric that Belt and Road is open to global participation and suggest that the initiative is also motivated by factors other than trade, such as China’s need to combat excess capacity at home.

In the past, the world has had similar conversations involving Chinese engagement abroad, most notably surrounding the issues of ‘land-grabbing’ in Africa, whereby Chinese firms began to engage in the agricultural market following the global increase in food prices. While the large scale investments were seen by some as an opportunity to modernise farming processes and boost output, others saw it as a way for China to increase dependency among developing nations.

More recently, governments from Malaysia to Pakistan are starting to rethink the costs of the projects encompassed by the Belt and Road Initiative. They point to Sri Lanka, where the government struggled to make its repayments for the port which had been financed and built by China, and was hence required to lease the port to a Chinese company for 99 years.

The Center for Global Development has identified eight more Belt and Road countries at serious risk of not being able to repay their loans, with the infrastructure and governments likely to face a similar fate to Sri Lanka’s own.

The affected nations – Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, the Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro, Pakistan and Tajikistan – are among the poorest in their respective regions and will owe more than half of all their foreign debt to China.

Critics worry China could use “debt-trap diplomacy” to extract strategic concessions – such as over territorial disputes in the South China Sea or to silence human rights violations. For example, In 2011, China wrote off an undisclosed debt owed by Tajikistan in exchange for 450 sq miles of disputed territory.

Some worry expanded Chinese commercial presence around the world will eventually lead to expanded military presence. Last year, China established its first overseas military base in Djibouti. Analysts say almost all the ports and other transport infrastructure being built can be dual-use for commercial and military purposes. Such concerns were raised in the case of the Sri Lankan port.

Already China has negotiated long-term leases on the following Asian ports:

Gwadar, Pakistan: 40 years

Kyaukpyu, Myanmar: 50 years

Kuantan, Malaysia: 60 years

Obock, Djibouti: 10 years

Malacca Gateway: 99 Years

Hambantota, Sri Lanka: 99 years

Muara, Brunei: 60 years

Feydhoo Finolhu, Maldives: 50 years

One geopolitical theory suggests that China is building a ‘string of pearls’ in the Indian Ocean, referring to their commercial and military facilities along their sea routes. Indian policymakers and government officials have expressed concerns over how these routes could affect Indian trade and territory. Furthermore, China’s diplomatic and commercial relationships with Pakistan has heightened the sentiment. China and India — the dragon and the elephant — as emerging economies have traditionally been pitted against each other as rivals, despite their economic diversification taking two relatively separate paths.

It is not only India who are concerned about this apparent monopolisation of strategic Asian ports. Emmanuel Macron, French President and European political figurehead expressed concern at the apparent strategy, saying “”the ancient Silk Roads were never just Chinese … New roads cannot go just one way.”. In Australia, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade said: “Australia welcomes the contribution that infrastructure initiatives can make to regional development, but it is important that such initiatives are transparent and open, uphold robust standards, meet genuine need, and avoid unsustainable debt burdens for recipient countries.”

Australia and China mutually benefit from their existing trade, economic and cultural relationships, and critics argue that the Belt and Road Initiative is nothing more than a strategic ploy for China to extend their powers throughout the world, most likely at the expense of others.

Regardless of intentions, an initiative of this scale will certainly alter the current structure of global power, and will lend itself to greater globalistaion efforts and provide some much needed Foreign Direct Investment to developing countries – something that the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (of which, China is not a member) have been promoting as a tool for stimulating economic progress for decades.

More information:

Study Guide: The History of the Silk Road

Study Guide: The Chinese Empire

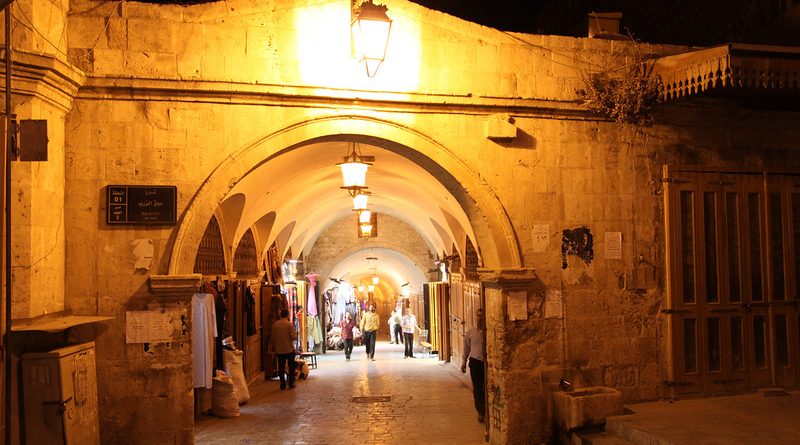

Watch: Bazaar – Silk Road Cities