The Chinese Empire

The Chinese Empire

China has a long and rich history stretching back several millennia, as far back as the 20th Century BC. The Chinese Empire does not refer to a singular dynastic power but rather several different ones, each of which held power over its many millennia of history.

THE 20 DYNASTIES OF CHINA

Xia Dynasty

The earliest known dynasty was the Xia Dynasty, which was in power from as early as 2070 BC before falling into obscurity around 1600 BC. Little is known about the Xia Dynasty and it was believed to be a mythical story for many years. It serves an important role in Chinese history due to its prevalence in a number of major texts such as the Bamboo Annals and the Records of the Grand Historian. Despite this, little archaeological evidence exists from this period, rendering much written information about the period unreliable.

Shang Dynasty

Encompassing the period otherwise known as the Chinese Bronze Age was the Shang Dynasty. While the exact date of its ascendancy is somewhat ambiguous, it is estimated that the Shang arose around 1600 BC. Unlike the preceding Xia Dynasty, the Shang Dynasty is supported by a wealth of archaeological evidence. The dynasty was centred around the Henan Province along the Yellow River. The dynasty was known for making a number of major advancements in the fields of astronomy, mathematics and military technology. Major urban centres included Zhengzhou and Anyang, the latter serving as the capital. The dynasty collapsed during the rule of Di Xin, a cruel leader who lost the support of his subordinates. During the Battle of Muye, the advancing forces of the ascendant Zhou Army secured victory as Xin’s followers defected and refused to fight. The King killed himself by burning his palace to the ground, leaving a power vacuum to be filled by the invading Zhou Dynasty

Zhou Dynasty

The longest-living dynasty in Chinese history, the Zhou Dynasty remained in power for over 8 centuries. It is generally divided into two separate periods-the Western Zhou (1046-771 BC) and the Eastern Zhou (771-256 BC). It is considered to be amongst the most influential periods in Chinese history, establishing political systems which would be put in place for millennia and creating a distinct cultural identity. The Zhou Dynasty coexisted with the Shang Dynasty for several hundred years and eventually consolidated rule over its rival and exerted control over the entirety of China. The Western Zhou was the less important of the two, peaking for about a century and declining thereafter. Little is known about the period beyond the names of its Kings and a general outline of events. The Zhou’s movements Eastwards represented the coming of the Eastern Zhou and a more illustrious period of history.

Spring and Autumn Period

The Eastern Zhou marked the beginning of the Iron Age in China, a major turning point in the country’s history. The first period of this, spanning 771-476 BC, is known as the Spring and Autumn Period, its name stemming from the ‘Spring and Autumn Annals’. The centralised Imperial family lost its power over this period as regional duchies emerged and consolidated power. As divisions began to emerge, a number of important developments occurred in the fields of education and academia. Confucius and several other intellectual figures were active at this time. It was also a period which saw significant infrastructural improvements in the forms of canals and roads.

Warring States

As divisions formed, conflict became increasingly prevalent. The final years of the Zhou Dynasty are better known as the Warring States Period. The duchies had declared themselves Kings and had begun more openly feuding with one another. Eventually, two states emerged from the conflict-the Qin and Chu dynasties, with Qin ultimately overcoming its closest rival and becoming the head of the first unified Chinese Empire. Despite the period being dominated by conflict, the Warring States Period also saw a number of major developments in the government systems.

Qin Dynasty

The first of dynasty of Imperial China, the Qin Dynasty only lasted for 15 years but was immensely important in its foundational legacies. Overseen by its founder Qin She Huang, the dynasty introduced a number of laws and systems which remained in place until the early 20th Century. The dynasty achieved its goal of establishing a unified centralised state of political power. It removed power from feudal lords and established strict control over the peasantry. The authoritarian government introduced standardised writing and measurement systems, a single currency and large-scale construction projects, including the initial Great Wall. It was also known for its anti-intellectualism, with book burning becoming common. The harshness of this regime caught up with it. After the first Emperor’s death, a brief power struggle emerged, which caused a rebellion to oust the dynasty from power. A brief transitional period followed, with the power vacuum being filled by the Han Dynasty.

Han Dynasty

Following the collapse of the Qin Dynasty, the Han Dynasty emerged as the next great period, exerting control over China for 400 years. It is considered to be one of the most illustrious periods in Chinese history, often labelled a golden age. The ethnic Chinese term ‘Han Chinese’ stems from this period, giving a sense of its importance. Established by rebel leader Liu Bang, the dynasty is divided into two periods-the Western Han (206 BC-9 AD) and the Eastern Han (25-220 AD), separated by the brief Xin Dynasty. The period was known for its vast cultural achievements, restoring the artistic and intellectual rigour the preceding Qin Dynasty repressed. Literature and music flourished while historical documentation improved significantly. Importantly, Buddhism was introduced from India during this period, a major cultural moment in Chinese history.

Western Han Dynasty

The Western Han Dynasty, under the rule of Liu Bang or Emperor Gaozu as he was retroactively known, made Chang’an its capital. Gaozu restored authority to some members of the nobility to quell an uprising following their contributions to the overthrowing of the Qin dynasty. This division of power was not long-lasting as these feudal lords were replaced by members of the Liu family due to questions surrounding their loyalty. This resulted in a number of uprisings, the most notable of which being the Rebellion of the Seven States in 154 BC. In the aftermath, the Han Kings’ powers were reduced significantly and the Imperial court played a more significant role in the oversight of their kingdoms. The lesser kings were rulers in the nominal sense but lacked major powers. The Western Han Dynasty was ended following the accession of Wang Mang, who established the Xin Dynasty.

Xin Dynasty

Wang Mang’s grip on power proved to be short-lived. He passed a number of sweeping reforms such as the abolition of slavery and the nationalisation of land in a bid of creating a harmonious society inspired by the works of Confucius and other scholars. These reforms, however well-intentioned, backfired and drew considerable opposition. This opposition intensified significantly following a series of major floods, which left vast swathes of the peasantry homeless and destitute. Rebel groups began to emerge and they eventually stormed Wang Mang’s palace and killed him. Another brief power struggle emerged but eventually the Han Dynasty was restored.

Eastern Han Dynasty

The second Han Dynasty, better known as the Eastern Han or the Later Han, was restored under the leadership of Emperor Guangwudi in 25 AD. This marked a return to the Western Han’s government institutions. The Eastern Han pursued a more aggressive foreign policy while trade and cultural exchange increased considerably. Contact was made with the Roman Empire, the Parthian Empire and many other foreign powers. The dynasty reached its zenith under Emperor Zhang in 75-88 AD, with Han society and culture reaching its apex. Thereafter, the dynasty began a slow decline. The eunuchs began to exert more and more political power and imposed authoritarian restrictions. Conflict intensified considerably as rival powers vied for control. The eunuchs were massacred by the military following the death of Emperor Ling in 189 AD and a power struggle emerged between military and nobility figures, dividing the Empire once more.

Three Kingdoms

With the Han Dynasty all but vanquished, a period of major political discord dominated China. Daoist and Yellow Turban rebellions were quashed and China entered one of the bloodiest periods in its history. The period is known as ‘the Three Kingdoms’, with three figures claiming control of the entirety of China. The states were Wei, Shu and Wu. This relatively short period is deeply ingrained within Chinese history with numerous figures entering the canon in an age of chivalry and heroism. Eventually, in 263 She was conquered by Wei, only to be overcome itself by the ascendant Jin Dynasty. The Three Kingdoms Period was a time of major technological advancement and the exploits of its major figures have been lionised in Chinese culture.

Western Jin Dynasty

In the aftermath of the turbulent and bloody Three Kingdoms Period came the Western Jin Dynasty, a period known for its relative stability. Attempts were made to enact political and economic reform in a bid to repress the rebellion of the nobility and restore the glory years of the Han dynasty. However, these attempts were in vain as in-fighting between rival clans caused thew Jin’s grip on power to disintegrate and foreign powers to emerge.

The Barbarian Invasions and the Sixteen Kingdoms

With the Jin dynasty in disarray, China was vulnerable to outside conquest, which came in the form of Liu Yu, a Xiognu warlord who began to conquer China’s North with the aid of Chinese bandits. Northern China subsequently fell under the rule of a number of warring barbarian factions for many centuries, which were referred to as the Sixteen Kingdoms.

Eastern Jin Dynasty

While the Western Jin Dynasty was displaced by invading foreign tribes, the East functioned as a refuge for exiled members of the royal family and the nobility. The royal family found themselves subjected to the domimion of the nobility, who functioned as oligarchies, often coming to blows with one another. This persistent conflict ensured that the Eastern Jin did not survive for long and was overthrown by the Liu Song Dynasty’s founder Liu Yu in 420, ushering in a new period now known as the Northern and Southern Dynasties.

Northern and Southern Dynasties

Another major period of conflict and disorder, the period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties lasted from the collapse of the Eastern Jin in 589 until the reunification of China under the Sui Dynasty’s Emperor Wen. It is considered to be a major transitional period in the country’s history, seeing Buddhism and Daoism become increasingly widespread while the Han Chinese diaspora spread southwards. The dominant philosophy of Confucianism began to wane and gave way to a diversification of intellectual thought while literature and the arts flourished.

Sui Dynasty

Following nearly 400 years of infighting and fragmentation, the Sui Dynasty reunified China. However, its authority would prove to be short-lived. The leadership of the Sui Dynasty attempted to enact sweeping political reform but ultimately overextended itself and collapsed. Its founder Wendi, a former member of the Northern Zhou aristocracy emerged as a major military power and established a new capital-Daxing and prioritised defence whilst engaging in foreign affairs. His military supremacy saw him easily overcome the Southern dynasties. He strengthened his standing with institutional reforms, establishing a more lenient penal code and expanding the central government. He conducted a major census and reformed the taxation system. Its most enduring physical legacy was the Grand Canal, the oldest and longest of its kind in the world and a major trading artery. Despite the dynasty’s early promise, it was brought to an abrupt and ignominious end during the Goguryeo-Sui War, a conflict with one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea. Civil unrest grew to such an extent that the dynasty was overthrown and the emperor assassinated.

Tang Dynasty

The Sui Dynasty’s successor-the Tang Dynasty is considered to be one of the cultural peaks of Chinese history. The power vacuum was quickly filled by the Li family, which oversaw a period of peace and prosperity. Expanding upon the reforms established by the Sui dynasty, the Tang Dynasty saw civil order form while culture reached new heights, the mediums of poetry and fine art flourishing particularly well. The Tang Dynasty ultimately reached its end as the central government eased control over the economy, which coupled with natural disasters to cause civil unrest amongst the agrarian population. Uprisings such as the Guangzhou massacre toppled the dynasty and led to yet another period of political unrest.

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms

Civil disorder gripped China for nearly 50 years, marking the arrival of a multi-state system. Northern China’s Imperial stronghold was dominated by five short-lived, successive regimes (Hou Liang, Hou Jin, Hou Han and You Zhou). Meanwhile, the South was divided into ten separate, stable regimes of varying size. This period was plagued by conflict and moral degradation.

Song Dynasty

Divided into two distinct periods-the Northern Song (960-1127) and the Southern Song (1127-1279), this was a major turning point in Chinese history. A time of considerable economic growth and expansion as foreign trade, commerce, urban growth and technological development all occurred. It was also a time of considerable population growth while Confucianism underwent a cultural revival. It was a time noted for the conflict with the Mongol Empire, which conquered the Song Dynasty in 1279.

Yuan Dynasty

Marking a dramatic change was the Yuan Dynasty, an empire established by Mongol leader Kublai Khan. An outlier of the Mongol Empire, Khan ruled over China in isolation from the rest of the Khanate. The Khanate ruled over China for nearly 100 years, synthesising Chinese traditions with Mongol military identity. Mongol rule brought initial economic and cultural success but eventually descended into feudalism and was ruled like a colony, a fatal error given China’s immense size. It was conquered by the emerging Ming Dynasty

Ming Dynasty

The initial Ming Emperor Hongwu established an austere, authoritarian political system which placed strong emphasis on the agricultural sector of the economy. As the dynasty developed, major economic change was implemented as foreign trade expanded significantly. The Great Wall of China was significantly developed into its current form. The dynasty collapsed following a series of natural disasters and crop failures, usurped by rebel leader Li Zicheng, who was shortly afterwards ousted himself by the Eight Banner army-the founders of the Qing Dynasty.

Qing Dynasty

China’s final dynasty was established in 1636 and ruled the country until the early 20th Century, its power extinguished in 1912. One of the largest empires in the history of the world, the Qing Dynasty created the territorial basis for modern-day China. This period saw a dramatic increase in population and an intensification of foreign policy as it acquired new territories, most notable Taiwan. Its aggression drew the ire of Western powers and conflict broke out. Despite late attempts at modernisation, the empire collapsed due to the divisions between the reformers and the hardliners.

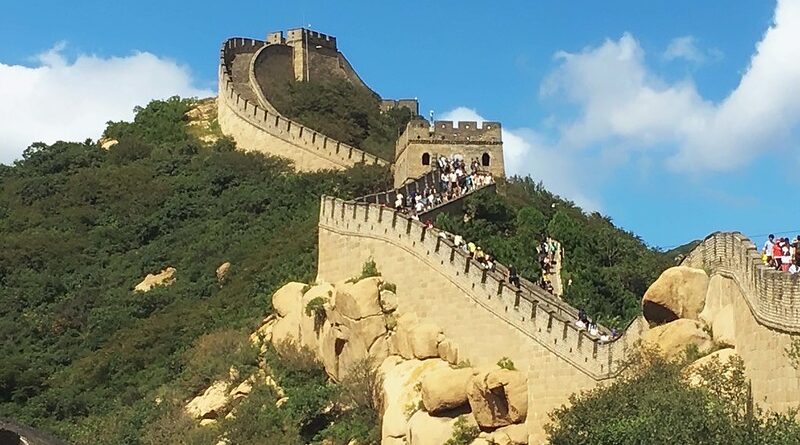

THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA

Without a doubt China’s most iconic and enduring landmark, the Great Wall of China is one of the most impressive physical accomplishments in human history. Straddling China’s historical northern border, the wall was built incrementally over several centuries as a means of fortification against invading forces, particularly the nomadic forces of the Eurasian Steppe, who regularly tried to invade and conquer China. The earliest walls date back to the 7th Century BC, and were added to in the years since. Major developments were made during the reign of China’s first Emperor Qin Shi Huang in the 3rd Century BC. The majority of the modern-day Great Wall date s back to the time of the Ming Dynasty in the 14th Century. Traversing an immense distance of over 13,000 miles, the Great Wall remains one of the most iconic and historically significant landmarks in the world.

RELIGION AND BELIEFS: From Buddhism to Confucianism

Religion in China has been an ever-changing and complex issue over several millennia. Historically, the country was dominated by Chinese folk religions, which have a strong emphasis on nature and ancestors and include the worship of a plethora of different deities. The concept of Yin and Yang is a central principle to Chinese folk religions. In modern times, adherents to Chinese Folk Religion still accounts for nearly 75% of the country’s population, although this also includes worshippers of Taoism and Confucianism, two officially recognised religions. Taoism is heavily rooted in the philosophical concept of ‘The Way’, the natural order of the universe. It first emerged in the 2nd Century and remains a focal point of Chinese religious and cultural identity. Equally important is Confucianism, which first emerged in the 6th Century BC. A major influence on Taoism, Confucianism is named after the philosopher Confucius and places strong emphasis on the importance of family. It is more humanistic than spiritual. Confucianism has gone through cycles of significance, particularly important during the Shang, Han and Tang dynasties. It remains immensely important in modern times. Buddhism accounts for 15% of the country’s population. Having arrived in China due to the increase of cultural and physical exchange associated with the Silk Road, Buddhism emerged during the end of the Han dynasty during the 1st Century. During the period of political discord and civil conflict which followed the collapse of the Han dynasty, Buddhism became increasingly widespread amongst the population, reaching a point of religious supremacy as it competed with the country’s native religions. Overall, there are five recognised religions in China-Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, Christianity and Islam-however, it is the first three which are of major cultural significance, forming the ‘three teachings’ of Chinese culture. While these views were repelled during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960’s due to their perceived regressiveness, they have since been formally embraced as a major part of the country’s national identity.

TRADE SECRETS: Tea, Porcelain, Silk

The Silk Road, a series of networks, which connected the Eastern and Western worlds, opened Europe to a number of important commodities from China.

Tea

Tea is amongst the most significant of these. Consumption and production of tea in China dates back nearly 5000 years. Tea has a major cultural and spiritual significance in China, having been believed to relieve a number of sicknesses and ailments. It emerged as a recreational beverage during the Tang Dynasty and spread throughout East Asia. Tea was imported to Europe first by the Portuguese in the 16th Century, becoming popular in Britain around 100 years later and eventually becoming a cultural institution. Due to the Chinese monopoly on production, the British Empire established major manufacturing hubs in India in a bid to overcome this domination of the market. In modern times, nearly two thirds of the world’s tea production comes from China and India.

Porcelain

China’s importance in the development of porcelain is so significant that the ceramic is commonly known as ‘china’ in Europe. A resilient material known for its toughness and distinct white colour, porcelain took many years to perfect, with its progenitors dating back to as early as the 17th Century BC. The manufacturing process was perfected during the Han Dynasty and a major industry surrounding it soon emerged. Exportation to Europe began during the Ming Dynasty as its popularity grew immensely, proving to be a lucrative source of trade for the country as Portuguese and Dutch merchants instigated direct trade.

Silk

Giving the Silk Road its name, the eponymous product has been an immensely popular and important export of China. As the birthplace of the product, China has been a major development for silk for over 8000 years. The heart of the Chinese textiles industry, silk production played a major role in China’s trading relationships with Western countries. It proved so lucrative that the Chinese went to great lengths to ensure that the manufacturing process remained a secret so as to preserve their monopoly. In modern times, Chinese silk production accounts for nearly three quarters of the world’s total and exports accounting for nearly 90%.

THE FORBIDDEN CITY

Now one of China’s most iconic landmarks and tourism attractions, the Forbidden City is located in the heart of the country’s capital city Beijing and is a site of major cultural and historical significance. A vast palace complex built during the Ming Dynasty, it functioned as the home of the Emperor and the government’s political centre for nearly 500 years. Consisting of an astounding 980 buildings, the Forbidden City spans an area of 180 acres. It is considered to be perhaps the definitive example of Chinese palatial architecture. Since the collapse of the Chinese monarchy in 1912, the Forbidden City has changed purposes repeatedly. In modern times, it is a major tourism attraction, administered by the Palace Museum.

THE OPIUM WARS

One of the most notable series of conflicts in Chinese military history, the Opium Wars were two separate wars between China and the British Empire during the 19th Century.

The First Opium War lasted nearly three years, from 1839 to 1842. It stemmed from trade disputes between Great Britain and China. Trade between the two countries was strong, with demand for Chinese goods such as tea, porcelain and silk very high in Britain. Chinese demand for British goods was less high and overwhelmingly focused on silver, which saw a shortage in Britain. In order to force the Chinese hand, British merchants with the assistance of the East India Company, began to smuggle opium into the country through illegal channels, demanding payment in silver, for which they would purchase Chinese goods such as tea. Indeed, by the outbreak of the war, opium sales paid for the tea trade. This outraged China due to the massive addiction problems it caused as well as the upset of the balance of trade. They forced British trade figurehead Charles Elliot to hand over and destroy opium supplies, which caused strained relations to reach breaking point and conflict to emerge. The war was dominated by naval battles, which the British won with ease. Despite being drastically outmatched, they secured victory after nearly 3 years. Victory was sealed with the Treaty of Nanking, which saw the British resume free trade and seize control of Hong Kong from the Chinese. The defeat significantly affected the dynasty’s international prestige and remains a dark period during Chinese history. It marked the beginning of modern Chinese history and what some nationalist historians describe as the ‘Century of Humiliation’.

The Second Opium War began over a decade later following European frustrations over the Chinese government’s failure to comply with the terms of the Treaty of Nanking. European powers wanted the country to be more open to their merchants as well as the legalisation of the lucrative opium trade. China, still frustrated by the previous conflict, refused to negotiate with any European countries. Tensions reached boiling point in 1856 when the Chinese boarded a British ship-the Arrow which was owned and manned by Chinese traders. The British demanded their release and upon Chinese refusal, conflict between the two escalated significantly. The British asked other Western powers for military assistance, with the French eagerly agreeing. Although peace was agreed in 1858, conflict continued as China refused to adhere to certain terms of the treaty. Peace was finally ratified with the Convention of Peking and the Chinese ceded even more territory to the British. Other terms included the freedom of religion in China, the legalisation of the opium trade and reparations to the British and the French.

These conflicts were a major period of humiliation for China and informed a lingering sense of hostility towards the West which remained intact for many years.

THE LAST EMPEROR

Centuries of monarchy in China finally culminated with the reign of Emperor Puyi, whose forced abdication in 1912 marked a major turning point in the country’s history. Reigning from the age of 2 until the age of 6, his brief stint in power was ended during the Xinhai Revolution of 1911. This was mainly prompted by the deep decline of the Qing State as a part of the ‘Century of Humiliation’, which saw Chinese international prestige wane considerably. Major disgraces included the defeats of the opium wars amongst others. This caused unrest and eventually rebellion to develop, causing 2000 years of imperial rule to come to an end. Puyi was still permitted to live in the Forbidden City and went by the new anglicised name of Henry Puyi. He was briefly restored to power for less than two weeks in 1917 by royalist warlord Zhang Xun. He fled Beijing in 1924 to live in the Japanese concession, installed as president and eventually Emperor of Manchukuo, the Japanese puppet state in Manchuria. In the aftermath of the Second World War, he was captured by Russian forces and returned to stand trial in China as a war criminal. Imprisoned for nearly a decade, he was freed in 1959 and lived in Beijing as a civilian, eventually pursuing a career in academia.

CULTURAL REVOLUTION

The second half of the 20th Century has been a major period of transition in China. In the aftermath of the Second World War and the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Chinese Communist Revolution broke out following the Chinese Communist party’s ascent into power. Eventually, after four years of conflict and millions of death, Communist leader Mao Zedong declared victory in 1949, proclaiming the beginning of the People’s Republic of China. Communist rule was effectively consolidated and embedded into the public consciousness during a period known as the Cultural Revolution, lasting from 1966 to 1976 under Mao’s oversight. This period saw a purge of lingering elements of capitalist and traditional Chinese culture from society. Mao Zegong Thought, or Maoism became the dominant ideological thought of the country. Making up for the failure of Mao’s earlier attempt to transform the country from an agrarian economy into a socialist state, the Cultural Revolution removed bourgeoisie elements through increasingly violent and inhumane means. It is believed that 1.5 million people were executed during the Cultural Revolution with millions of others suffering imprisonment, torture or public humiliation. Following Mao’s death, these policies were mostly dismantled and the Revolution deemed a major setback to Chinese modernisation.