The Mystery of The Minoan Civilization

The beginnings of Cretan history are locked in the darkness of the Neolothic period which ended around 2600BC. About this time, during the Aegean Bronze Age, there emerged on Crete a civilisation that became known as the Minoan Civilization. It has been described as the earliest of its kind in Europe, a so called “the first link in the European chain”.

The Minoans represented the first advanced civilization in Europe, leaving behind massive building complexes, tools, artwork, writing systems, and a wide trading network.

The civilization was rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century through the work of British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. The name “Minoan” derives from the mythical King Minos and was coined by Evans, who identified the site ruins at Knossos with the legend of the labyrinth and the Minotaur.

Mythology

In Greek mythology, Minos was a King of Crete, son of Zeus and Europa. Every seven years, he made King Aegeus pick seven young boys and seven young girls to be sent to the labyrinth, to be eaten by the Minotaur. After his death, Minos became a judge of the dead in the underworld.

The many rooms of the palace at Knossos were so oddly shaped and disordered to Evans that they reminded him of the labyrinth of the Minotaur. According to myth, Minos’ wife had an illicit union with a white bull, which lead to the birth of a half bull and half man, known as the Minotaur. King Minos had his court artist and inventor, Daedalus, build an inescapable labyrinth for the Minotaur to live in.

The Minoan civilization flourished on Crete and other Aegean islands such as Santorini from c. 3000 BC to c. 1450 BC until a late period of decline, finally ending around 1100 BC.

Minoan Palaces

Minoan palaces were divided into numerous zones for civic, storage, and production purposes; they also had a central, ceremonial courtyard.

The most well known and excavated architectural buildings of the Minoans were these palaces that acted as administrative centres.

When Sir Arthur Evans first excavated at Knossos, not only did he mistakenly believe he was looking at the legendary labyrinth of King Minos, he also thought he was excavating a palace. However, the small rooms and large storage vessels, and archives led researchers to believe that these palaces were administrative centers. Even so, the name became ingrained, and these large, communal buildings across Crete are known as palaces.

Although each one is unique, they share similar features and functions. The largest and oldest palace centers are at Knossos, Malia, Phaistos, and Kato Zakro.

These large and elaborate palaces were up to four stories high, featuring elaborate plumbing systems and decorated with frescoes. The most notable Minoan palace is that at Knossis, followed by that at Phaistos.

The complex at Knossos provides an example of the monumental architecture built by the Minoans. The most prominent feature on the plan is the palace’s large, central courtyard. This courtyard may have been the location of large ritual events, including bull leaping, and a similar courtyard is found in every Minoan palace centre.

Several small tripartite shrines surround the courtyard. The numerous corridors and rooms of the palace center create multiple areas for storage, meeting rooms, shrines, and workshops.

The absence of a central room and living chambers suggest the absence of a king and, instead, the presence and rule of a strong, centralized government.

The palaces also have multiple entrances that often take long paths to reach the central courtyard or a set of rooms. There are no fortification walls, although the multitude of rooms creates a protective, continuous façade. While this provides some level of fortification, it also provides structural stability for earthquakes.

Wells for light and air provide ventilation and light. The Minoans also created careful drainage systems and wells for collecting and storing water, as well as sanitation.

Their architectural columns are uniquely constructed and easily identified as Minoan. They are constructed from wood, as opposed to stone, and are tapered at the bottom. They stood on stone bases and had large, bulbous tops, now known as cushion capitals. The Minoans painted their columns bright red and the capitals were often painted black.

Frescoes

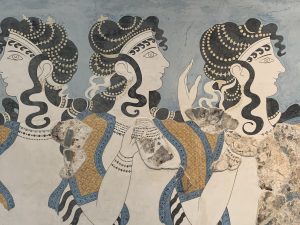

Minoan Frescoe

Because the Minoan alphabet, known as Linear A , has yet to be deciphered, scholars must rely on the culture’s visual art to provide insights into Minoan life.

The visual art – known as frescoes – discovered in locations such as Knossos and Akrotiri ,on the island of Santorini, inform us of the plant and animal life of the islands of Crete and Thera (Santorini), the common styles of clothing, and the activities the people practiced. For example, men wore kilts and loincloths. Women wore short-sleeve dresses with flounced skirts whose bodices were open to the navel, allowing their breasts to be exposed.

Vase Painting

Minoan ceramics and vase painting are uniquely stylized and are similar in artistic style to Minoan wall painting. As with Minoan frescoes, themes from nature and marine life are often depicted on their pottery. Similar earth-tone colors are used, including black, white, brown, red, and blue.

Kamares ware, a distinctive type of pottery painted in white, red, and blue over a black backdrop, is created from a fine clay. The paintings depict marine scenes, as well as abstract floral shapes, and they often include abstract lines and shapes, including spirals and waves.

These stylized, floral shapes include lilies, palms, papyrus , and leaves that fill the entire surface of the pot with bold designs. The pottery is named for the location where it was first found in the late nineteenth century — a cave sanctuary at Kamares, on Mount Ida. This style of pottery is found throughout the island of Crete as well in a variety of locations on the Mediterranean.

Read: The Handmade Delights of Crete

Minoan Symbols

The Double Axe

Whilst the double axe continued to retain its practical use as a forestry and hewing tool in Minoan culture, it became imbued with a special religious significance from an early stage, which can also be seen in Thracian and mainland Greek art.

For the Minoans on Crete, the symbol was especially associated with female divinities and priestesses and thus became a synonym for matriarchy. To find such an axe in the hands of a Minoan woman would therefore indicate that she held a powerful position within Minoan society.

Bull Leaping

Although the specifics of bull leaping remain a matter of debate, it is commonly interpreted as a ritualistic activity performed in connection with bull worship. In most cases, the leaper would literally grab a bull by his horns, which caused the bull to jerk his neck upwardly. This jerking motion gave the leaper the momentum necessary to perform somersaults and other acrobatic tricks or stunts.

Traders And Foreign Influence

The Minoans were primarily a mercantile people who engaged in overseas trade. After 1700 BC, their culture indicates a high degree of organization. Minoan-manufactured goods.

The Minoan period saw extensive trade between Crete, Aegean, and Mediterranean settlements, particularly the Near East. Through their traders and their artists, the Minoans’ cultural influence reached beyond Crete to the nearby Cyclades group of Greek islands, and to Egypt, Cyprus and the coasts of Turkey, Lebanon and Israel

Thera

The Minoans settled on other islands besides Crete, including the volcanic, Cycladic island of Thera (present-day Santorini). The volcano on Thera erupted in mid-second millennium BCE and destroyed the Minoan city of Akrotiri. Akrotiri was entombed by pumice and ash and since its rediscovery has been referred to as the Minoan Pompeii. The frescoes on Akrotiri were preserved by the blanketing volcanic ash.

Some of the best Minoan art is preserved here. A fresco of saffron-gatherers is well-known. The Minoans traded in saffron, which originated in the Aegean basin. According to Evans, saffron was a substantial Minoan industry and was used for dye. Other archaeologists emphasize durable trade items: ceramics, copper, tin, gold and silver. The saffron may have also had a religious significance. The saffron trade, which predated Minoan civilization, was comparable in value to that of frankincense and black pepper.

The influence of Minoan civilization is seen in Minoan handicrafts on the Greek mainland. And Connections between Egypt and Crete are prominent; Minoan ceramics are found in Egyptian cities, and the Minoans imported items, such as papyrus ,and architectural and artistic ideas from Egypt. Egyptian hieroglyphs might even have been models for the Cretan hieroglyphs from which the Linear A and Linear B writing systems developed.

Religion

Minoan religion apparently focused on female deities, with women officiants. While historians and archaeologists are unsure of an outright matriarchy, the predominance of female figures in authoritative roles over male ones seems to indicate that Minoan society was matriarchal.

Government

Because their language has yet to be deciphered, it is unknown what kind of government was practiced by the Minoans, though the palaces and throne rooms indicate a form of hierarchy.

Fashion

Minoan men wore loincloths and kilts. Women wore robeswith short sleeves and layered, flounced skirts. The robes were open to the navel, exposing their breasts. Women could also wear a strapless, fitted bodice, and clothing patterns had symmetrical geometric designs.

Other Minoan sites

The ruins of Minoan sites are scattered across Crete. The most notable if these are at Phaistos and Agia Triada. Gortyn was also inhabitated by the Minoans but when the Romans conquered Crete they made it their capital.

Language and writing

Several writing systems dating from the Minoan period have been unearthed in Crete, the majority of which are currently undeciphered.The most well-known script is Linear A dated to between 2500 BC and 1450 BC.Linear A is the parent of the related Linear B , which encodes the earliest known forms of Greek. Several attempts to translate Linear A have been made, but consensus is lacking and Linear A is currently considered undeciphered. The language encoded by Linear A is tentatively dubbed “Minoan”. When the values of the symbols in Linear B are used in Linear A, they produce unintelligible words, and would make Minoan unrelated to any other known language. There is a belief that the Minoans used their written language primarily as an accounting tool and that even if deciphered, may offer little insight other than detailed descriptions of quantities.

Linear A is preceded by about a century by the Cretan hieroglyphs It is unknown whether the language is Minoan, and its origin is debated. Although the hieroglyphs are often associated with the Egyptians, they also indicate a relationship to Mesopotamian writings. They came into use about a century before Linear A, and were used at the same time as Linear A (18th century BC; MM II). The hieroglyphs disappeared during the 17th century BC (MM III).

The Phaistos Disc

The Phaistos Disc, discovered in the ruins of Phaistos in southern Crete, features a unique pictorial script. Because it is the only find of its kind, the script on the Phaistos disc remains undeciphered.

Because the Minoans primarily wrote in the undeciphered Linear A and also in undeciphered Cretan hieroglyphs, encoding a language, hypothetically labelled Minoan, has been unsuccessful. The reasons for the slow decline of the Minoan civilization, beginning around 1550 BC, are therefore unclear. Theories include Mycenaean invasions from mainland Greece and the major volcanic eruption of the the volcano on Santorini.

Decline and The Mycenaeans

Minoan palace sites were occupied by the Mycenaeans around 1420–1375 BC. Mycenaean Greek, was written in Linear B, so we know more about the Mycenaeans who tended to adapt (rather than supplant) Minoan culture, religion and art, continuing the Minoan economic system and bureaucracy.

By Ian Cross