The Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire occupies a special place in the collective consciousness of the West, at once a dark star on the eastern horizon, threatening the very existence of Western civilisation, and at the same time a source of endless fascination and enchantment, the physical realisation of the wildest Orientalist fantasy. Often identified in the popular imagination of the West as only one step removed from the realm of the Anti-Christ, the Ottoman Empire was at the same time admired for its enlightened attitude towards peoples of other faiths, a place where Jews and Christians, both Catholic and Orthodox, could live side by side with Muslim Turks — they may not have liked each other especially, but at least under Ottoman rule, they weren’t slitting each other’s throats.

The Ottoman military, the principal instrument of their success, was also admired as much as it was feared. The first standing army since the Roman empire, with an institutionalized system of conscription, salaried professionals, elite infantry and cavalry divisions, and cutting-edge artillery and sappers, its organisation and tactics were studied and copied by rival powers and laid down the foundations for the modern armies of today.

The Ottomans were also celebrated for their achievements in the arts and sciences, particularly architecture and engineering — the latter were more readily accessible to Western observers, whereas other areas of outstanding Ottoman creative achievement, such as poetry and calligraphy, could only be properly appreciated by those who had made a serious study of Islamic culture.

The Early Ottomans

By and large, though, for much of their 600-year rule, the Ottomans were viewed by the West more in negative terms than positive, a kind of repository for the moral failings of the world and its collective sins and vices, if not the fons et origo of all evil. Thus, in spite of their acknowledged religious tolerance and other enlightened attitudes regarding the governance of the peoples they had subdued, the Ottomans were seen as a cruel and vengeful people, who revelled in blood letting and atrocity.

A famous instance of the alleged barbarity of the Turk was the mass execution of Hungarian prisoners of war following the Battle of Mohács in 1526, when 2,000 captive Hungarian soldiers, including many notable noblemen and leaders, were decapitated on the expressed orders of the Ottoman Sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent. Suleiman, for his part, seems to have been as laconic as he was magnificent, simply noting in his personal diary for that day: “The Sultan, seated on a golden throne, receives the homage of the viziers and the beys, massacre of 2,000 prisoners, the rain falls in torrents.”

Suleiman was not exceptional when it came to barbarous deeds. The Venetian ambassador to the seventeenth-century court of Murad IV, describes the sultan as turning “all his thoughts to revenge, so completely that, overcome by its seductions, stirred by indignation, and moved by anger, he proved unrivalled in savagery and cruelty. On those days that he did not take a human life, he did not feel that he was happy and gave no sign of gladness.”

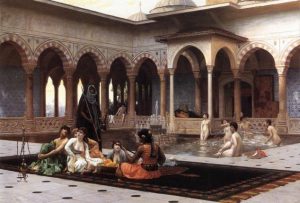

And it wasn’t just cruelty and violence that the Ottomans were famous for, but other vices too: avarice, duplicitousness and moral degeneracies of every kind. Most especially they were associated with wantonness and sexual excess — Sultan Murat III was said to have fathered 112 children, while the haremof the Topkapi Palace was famous for being home to some 400 concubines, procured solely for the pleasure of the Sultan!

East and West: Clash Of Civilisations

This demonisation of the Ottoman, was no more than one might expect given the threat posed to the Christian West by the seemingly unstoppable westward expansion of their empire during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Europe had been there once before with the Mongol invasion of Poland, Hungary and Croatia in the thirteenth century.

With the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and subsequent Ottoman advances into Europe in the course of the following century it must have seemed that the dreaded Gog and Magog were once more on the march and hammering at the gates of Christendom — Gog and Magog were peoples or lands mentioned in the Old Testament, who by the medieval era had come to be identified as the ultimate embodiment of the forces of darkness and evil: When the thousand years are over, Satan will be released from his prison and will go out to deceive the nations in the four corners of the Earth—Gog and Magog—and to gather them for battle. In number they are like the sand on the seashore (Revelation 20: 7-10).

It is tempting to view this confrontation between of the Muslim Ottoman and the Christian West in medieval Europe as a “clash of civilisations,” an idea that has a popular resonance in today’s post 9/11 world. And in a way it was, at least as seen from a European perspective.

Thus, Edward Said writes that in the eyes of the West, Islam came “to symbolise terror, devastation, the demonic, hordes of hated barbarians … a lasting trauma.” “Until the seventeenth century,” he continues, “the ‘Ottoman peril’ lurked alongside Europe to represent for the whole of Christian civilization a constant danger, and in time European civilization incorporated that peril and its lore, its great events, figures, virtues, and vices, as something woven into the fabric of life” (Orientalism, 1978: 59-60).

Where the Ottomans were concerned, however, their engagement with the West was rather more accommodating, based first and foremost on pragmatic considerations rather than an ideological rejection of all things European. Though intent on conquering as much of Eastern Europe as they could by force of arms, the Ottomans had no particular interest in converting the peoples they had subjugated to Islam. On the contrary, they were perfectly content to let those whom they had over run to continue to practice their own religions, be administered by their own laws and, except where Muslims were involved, be tried by their own legal systems.

The term “clash of civilisations” was first used by Bernard Lewis in an article in the September 1990 issue of The Atlantic Monthly, entitled ‘The Roots of Muslim Rage’, but subsequently became more closely identified with Samuel P. Huntington’s prophesy — now some twenty-years old — that henceforth “The great divisions among humankind and the dominating source of conflict will be cultural … and the fault lines between civilisations will be the battle lines of the future” (Huntingdon ‘The Clash of Civilizations?’, Foreign Affairs, Summer 1993).

When the Jews, for example, were expelled from Andalusia following the reconquest of Spain in 1492, many of them moved to Istanbul, where they were welcomed for their business connections and commercial expertise; the Ottoman Empire was nothing if not cosmopolitan.

Not that the Ottomans were especially benevolent or well-disposed towards non-Muslims. On the contrary, non-Muslims were treated as second-class citizens, and looked down upon as generally inferior beings, if not “beasts” (rayah), whose religion and other traditional practices would always have to defer to those of True Believers. Not only that, but non-Muslims also had to pay extra taxes and they were often treated in humiliating ways — for example in Damascus, Christians were forbidden to ride animals of any kind, not the humble donkey.

And then, of course, they were subject to the devşirme levy, a literal “harvest of children”, where young boys (and the occasional girl if the Sultan’s harem needing topping up) from non-Muslim families — mainly Christians communities in the Balkans — were forcibly removed from their homes at around the age of seven or eight, and brought to Constantinople, where they were made to convert to Islam and then enrolled one of the four imperial institutions — Palace, Scribes, Religious or the Military — whereupon they would receive an education that would prepare them for a career in the service of the Ottoman state.

But if the Ottomans considered themselves to be morally and materially superior to the West in most things — at least during the first half of their 600-year rule — they were quite happy to cherry-pick the best of European science and the arts as and when it pleased them.

The Ottomans, Western Culture & Art

Mehmed the Conqueror of Constantinople, was steeped in Classical culture and liked to think of himself as a latter-day Alexander the Great and heir to the Roman Caesar!

Though a firm believer in Islam and the efficacy of Sharia law, in later life he worshiped Christian relics and commissioned the Venetian artist Gentile Bellini to paint his portrait in a flagrant transgression of the Islamic proscription forbidding representational art.

This Europhilia was not a particular quirk of Mehmed. Ottoman scholars translated the works of ancient Greek philosophers and scientists into Arabic and Turkish, while European geographical discoveries made during the great Age of Exploration, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, soon found their way onto Ottoman maps, most famously Admiral Piri Reis’ World Map of 1513.

Similarly, Ottoman intelligence was well-informed about the latest European technical advances, especially in matters relating to the military sciences and engineering, while Leonardo da Vinci was invited by Sultan Bayezid, Mehmed’s successor, to submit a proposal to for a floating pontoon bridge across the Golden Horn.

If Christian Europe viewed the Ottomans on their doorstep with horror and alarm — an existential menace that threatened to penetrate the very heart of Christendom — the Ottomans looked to the West with a more sanguine eye and were happy to take the best that Europe had to offer and adapt it to their own ends. Even on the Christian side of the equation, it was never a simply a case of black or white, good or evil, where the Ottomans were concerned.

The first appearance of Ottoman Turkish troops on European soil in 1345 was as Byzantine mercenaries, while Venice was ever in cahoots with Istanbul, even when the rest of Europe was waging war on the Infidel. And come the Reformation and the emergence of a Protestant constituency in northern Europe, for some Christians, at least, the Ottomans no longer looked like the bad guys when they shared a common enemy — the Catholic-based Holy Roman Empire.

In the latter instance, the Ottomans were quite happy to enter into a rapprochement with the Protestant north, whose dominions lay at one remove from their borders. Thus we find Sultan Murad III exchanging letters with Queen Elizabeth I and arguing for an alliance between England and the Ottoman Empire, for as he points out Islam and Protestantism had “much more in common than either did with Roman Catholicism, as both rejected the worship of idols.”

Indeed, the closer one looks for a clash of civilisations, the more the notion seems to recede over the horizon. If ever there was such a thing outside of the rhetoric of popes and kings, then perhaps it can only be really applied to the period of the early crusades and the battle for the Holy Land.

Less than a hundred years after the fall of Constantinople, we find the Ottomans fighting alongside the French in the Italian Wars of 1536–1538 and 1542–1546. Needless to say, this was hardly conceived as a pact with the Devil were the two protagonists were concerned, though their common enemy on both occasions, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, might have seen it that way.

No Longer The Turkish Menace

By the end of seventeenth century, following the failure of the Ottomans to take Vienna in the 1683 — this was their second attempt on the city — and their subsequent defeat at the hands of the Holy League in the Great Turkish War of 1683–1699, the Ottomans were a spent force where further expansion into Europe was concerned.

At this point we see something of a sea change in European perceptions and representations of Ottoman society and culture. No longer the “Turkish menace”, Turks, Mussulmen, Moors and indeed anything that had an Oriental provenance began to be seen in a more favourable, even admirable, light, at least by the educated classes.

In the court society of Louis XIV, “turqueries” were all the rage, while gallant Moors and Muslim heroes began to appear in French theatre and literature. Muslim Spain (Al-Andalus) similarly acquired a positive connotation, while illustrated translations of One Thousand and One Nights provided an encyclopedia of exotic, not to say erotic, images and situations for a newly romanticised East. And yet despite this Orientalist revolution, which occurred in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the idea of an evil empire led by the Terrible Turk, hell-bent on the destruction of Western civilisation never disappeared entirely.

Indeed, it still persists in the collective consciousness of the West to this day, lurking in the shadows but ever ready to be summoned up, when required, in the rhetoric of modern-day leaders and politicians, not least George W. Bush who in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, famously equated his “war on terror” with a “crusade”.

Interestingly, Osama bin Laden, for his part, was equally happy to play along with the crusader imagery, confirming in an Al Jezeera interview that same year, that he did indeed see al-Qaeda’s struggle very much in terms of a clash of civilisations; no doubt, there are many on both sides of the East-West divide who would agree. This kind of political posturing can only succeed against a background of ignorance and prejudice and therefore any attempt to look beyond the stereotype can only be a good thing.

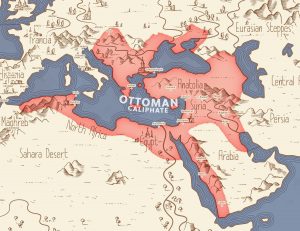

At its greatest extent of the empire in the late seventeenth century, Ottoman conquests in Europe extended westwards to the borders of modern-day Croatia, Austria, and the Slovak Republic, and eastwards as far the Crimea, taking in Moldova, Odessa and southern Ukraine along the way. In addition to the European half of modern-day Turkey (Eastern Thrace), other European countries within the Ottoman fold, at one time or another, included Greece, Albania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Bosnia Herzegovina, parts of Croatia, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary, that is to say the region collectively known as The Balkans.

The Balkans

The Balkans has long been one of the great crossroads of the world. Migrating tribes and barbarian invaders, merchants and missionaries, crusaders and ghazi (jihadi), colonisers and empire builders — ever since the Neolithic era, the Balkans have been a place where people from elsewhere came together.

Some were just passing through, others stayed and made the Balkans their home. Illyrians and Greeks, Romans and Slavs, Roma and Magyars, Bulgars and Turks, layer upon layer of ethnic, cultural and linguistic diversity, laid down over centuries.

Geography has played its role in accentuating this diversity — the Balkan Peninsula is a land of mountains and rivers, narrow coastal plains and highland pastures, with contrasting patterns of settlement and associated economies. And religion too, with pagan animism and local folkloric traditions being overlaid by Greek and Roman Gods; Roman Catholicism competing with the Eastern Orthodox Church; and both Christian Churches confronting Ottoman Sufism against a shifting background of religious tolerance, compromise, persecution and zealotry.

Since ancient times this has been contested ground. At different periods in the region’s long history, clan chiefs and feudal lords, medieval kings and their vassal princes, brigands and warlords have all fought with one another for territory and resources, and the control of trade routes. Ethnic and religious differences have only served to further complicate things, the history of the Balkans at a local level being one of bitter enmities, duplicitous allies and dodgy alliances, but one that has always been overlaid by the mantle of empire — Roman, Byzantine, and lastly Ottoman. And although the lasting influence of both Roman and Byzantine empires plays an important part in our story, ultimately it is the Ottomans who take centre stage — a dynastic succession of sultans stretching over six centuries that began with a dream and ended with ‘The Speech’.

The Collapse Of The Ottoman Empire Following The First World War

Not that the final collapse of the Ottoman Empire was the last word in the Ottoman story, for while the Empire may have officially ceased to exist with the abolition of the Sultanate by the Turkish Grand National Assembly on 1 November 1922, the repercussions of that momentous event are still being felt in Eastern Europe and the Middle East today. In the case of the Middle East, many of the problems that currently beset the region can be directly attributed to the fallout from the break up of the Ottoman Empire following the end of the First World War.

By the time all the postwar peace conferences had been concluded in 1922, Britain and France had received “mandates” from the newly formed League of Nations to administer huge chunks of the former Ottoman Empire to the east and south of Turkey and there can be no doubt that many of the decisions taken then not only shaped the territorial boundaries of the modern nation-states that now occupy the region, but also predicated the multiple conflicts that afflict them today, both internally and in relation to one another.

A large part of the problem was that in creating the territorial boundaries of what would eventually become today’s Iraq, Jordan, Israel, Syria, and Lebanon, too little attention was paid to the ancient tribal, ethnic, and religious differences that for centuries had been suppressed or at least contained by Ottoman rule.

As US President Woodrow Wilson’s close political advisor, Colonel Edward House, who also sat on the League of Nations Commission on Mandates, presciently remarked at the time, the lines being drawn in the desert sand by European mandarins and diplomats in 1922 were “making a breeding place for future war”.

Many of the same circumstances also prevailed in the Balkans, where ethnic, linguistic, cultural and religious divisions that had previously been held together by an Ottoman imperial glue several centuries in the making, also finally came unstuck. In this instance it was the hundred years or so that preceded and precipitated the final collapse of the Ottoman Empire that was the critical period. During this time, one sees the gradual emergence of several nationalist movements seeking to create their own independent nation state from Ottoman-held territories.

Early attempts at rebellion were typically led by small groups of Western-educated, romantically inclined intellectuals, who were not much good at organising an armed struggle; they were usually put down with ease and their leaders captured and executed.

Since, however, these local uprisings tended to provoke reprisals by Ottoman soldiers and irregulars against the civilian populations thought to be aiding and abetting the rebels, they helped to bring about a more widespread resentment against Ottoman rule.

Reported massacres of “innocent Christians” — the spectre of the “barbarous Turk” once more raising his ugly head — were exploited by rebel leaders to elicit support from Western Europe, while the neighbouring superpowers of Austria-Hungary and Russia, were only too happy to wade in and lend a hand in dismembering the “sick man of Europe” as Tsar Nicolas I described the ailing Ottoman Empire in 1853.Unable to contain these separatist movements on several fronts, the Ottoman Empire in Europe gradually started to come apart at the seams.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the majority of Balkan peoples were living in national states created along European lines — Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro, Romania and Serbia — but whereas the nation states of Western Europe had been several centuries in their formation, these new Balkan states were rather makeshift, overnight affairs, with invented monarchies and haphazard national boundaries.

Riven by ancient ethnic and religious divisions which straddled national boundaries, these newly-created polities were inherently unstable and prone to violent clashes as they competed with one another for territory and resources as the Ottoman Empire in Europe fell apart.

Since the final collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War was accompanied by the simultaneous disappearance of Austria-Hungary and Tsarist Russia this created a huge power vacuum in the region. Influenced, in part, by political developments in Italy and Germany, the Balkans drifted to the right in a move that saw fledgling democratic institutions swept away by authoritarian governments of various political hues, ranging from oligarchies and unconstitutional monarchs, to military regimes and fascist dictatorships.

German occupation of much of the Balkans during World War II, which was accompanied by the setting up of puppet states allied to the Axis powers, created a second postwar power vacuum following the capitulation of the Nazi regime in 1945.

This time around it was the communists who took advantage of the situation and once again the Balkans states found themselves on the front-line of a new divide between East and West, only now the “evil empire” was Soviet Russia, and it was Marxist-Leninism, rather than Islam, that constituted the moral and ideological threat.

“I urge you to beware the temptation of pride, the temptation of blithely declaring yourselves above it all … to ignore the facts of history and the aggressive impulses of an evil empire, to simply call the arms race a giant misunderstanding and thereby remove yourself from the struggle between right and wrong and good and evil,” Ronald Reagan, address to the National Association of Evangelicals, Orlando, Florida, 8 March 1983.

The Final Chapter

The final chapter in the post-Ottoman story of the Balkans begins with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989, when the region was again plunged into to a period of political instability, economic crisis and war. Enmities stretching back centuries once again erupted in a further round of blood-letting and ethnic cleansing that pitted Croat and Serb against Bosniak, Christian against Turk.

This was an ancient conflict dating back to the fourteenth century when Serbian Prince, Lazar Hrebeljanović, confronted the invading army of the Sultan Murad I at Kossovo Polje in 1389. This was a battle in which both Lazar and Murad lost their lives, with heavy casualties on both sides, but it was an important Ottoman victory nonetheless for it laid the foundation for further Ottoman conquests into Europe in the following century.

Six hundred years later, the Battle of Kosovo was being fought all over again in the Bosnian conflict of the early 1990s and it was only with the final, violent disintegration of Yugoslavia in 1995, and the resurrection of its dismembered parts as separate independent nations — Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro and Macedonia — that the ghosts of the Ottoman sultans could finally be laid to rest.